Abstract

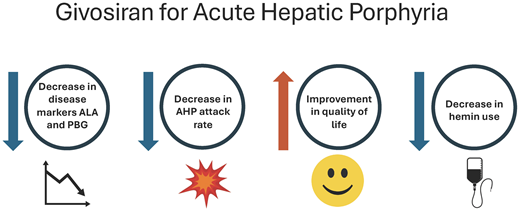

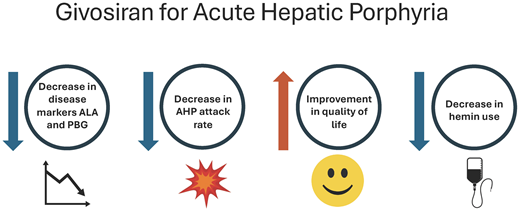

The acute hepatic porphyrias (AHPs) are a family of rare genetic diseases associated with attacks of abdominal pain, vomiting, weakness, neuropathy, and other neurovisceral symptoms. Pathogenic variants in 1 of 4 enzymes of heme synthesis are necessary for the development of AHP, and the onset of acute attacks also requires the induction of δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase 1 (ALAS1), the first and rate-limiting step of heme synthesis in the liver. Givosiran is an RNA interference medication that inhibits hepatic ALAS1 and was designed to treat AHP. In 2019 the US Food and Drug Administration approved givosiran for AHP based on positive results from a phase 3 clinical trial of 94 patients with AHP who demonstrated a marked improvement in AHP attacks and a substantial decrease in δ-aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen, the primary disease markers of AHP. A long-term follow-up study demonstrated continued improvement in AHP attack rates, biochemical measures of disease, and quality of life. Real-world studies have also confirmed these results. Common side effects include injection site reactions, hyperhomocysteinemia, and abnormalities of liver and renal biochemistries. This article reviews the studies that led to givosiran approval, discusses real-world clinical data, and highlights remaining questions in the treatment of AHP.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the data leading to givosiran approval

Review real-world clinical experience with givosiran

Explain givosiran's role in the management of AHPs

CLINICAL CASE

A 36-year-old woman was hospitalized for severe abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and an inability to tolerate oral intake that began while on a volunteer trip to Brazil. She had experienced a similar hospitalization several months prior, although an etiology of her symptoms was not determined at that time. After extensive testing, a urine porphobilinogen (PBG) returned at 130 mg/g creatinine (normal <2 mg/g creatinine) and a pathogenic variant in hydroxymethylbilane synthase (HMBS p.Arg255*) was identified. She was treated with intravenous (IV) hemin, and her symptoms resolved within 7 days. She had 4 additional attacks over the next year, each treated with hemin. Subsequently, she enrolled in the phase 3 clinical trial of givosiran and then continued monthly givosiran at 2 mg/kg subcutaneously for 5 years. Over that time, she experienced approximately 3 episodes of mild acute intermittent porphyria–related (AIP) symptoms that did not require hospitalization or treatment with hemin.

Introduction

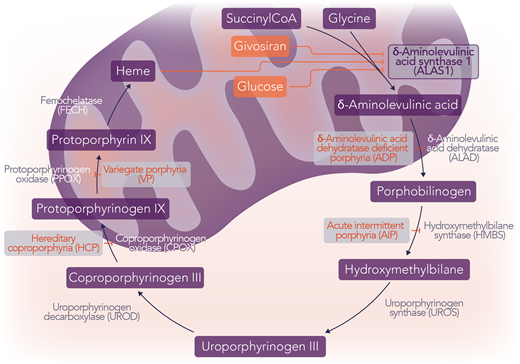

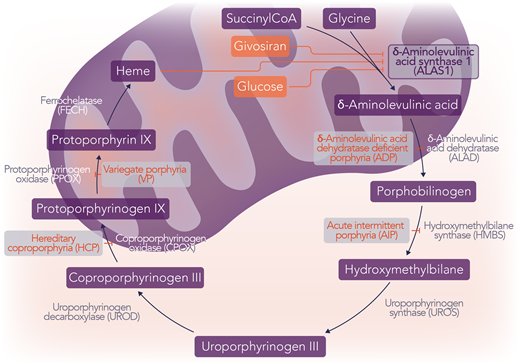

The acute hepatic porphyrias (AHPs) are a family of rare genetic diseases, each characterized by deficiencies in 1 of 4 enzymes of heme synthesis.1 These deficiencies can lead to the accumulation of the intermediates, PBG and δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), in the setting of upregulation of the first and rate-limiting step of heme synthesis, ALA synthase 1 (ALAS1).1 When this occurs, patients may experience episodic acute attacks and often chronic symptoms, including abdominal pain, weakness, neuropathy, vomiting, hypertension, seizures, and mental status changes, among other neurovisceral symptoms.1 The 4 AHPs are AIP, variegate porphyria (VP), hereditary coproporphyria (HCP), and ALA dehydratase deficiency porphyria (ADP), which result from pathogenic variants in HMBS, protoporphyrinogen oxidase, coproporphyrinogen oxidase, and ALA dehydratase (ALAD), respectively (Figure 1).1

The AHPs and hepatic heme regulation. The 4 AHPs are AIP, VP, HCP, and ADP, which result from pathogenic variants in HMBS, PPOX, CPOX, and ALAD, respectively. ALAS1 is the first and rate-limiting step of heme synthesis. The induction of ALAS1 is responsible for the acute neurovisceral attacks of AHP and the accumulation of the neurotoxic intermediates ALA and PBG. Givosiran is an RNA interference medication that targets hepatic ALAS1, decreasing the levels of the ALAS1 enzyme. Hemin is intravenous heme that exerts its effect by negative feedback on ALAS1. Additionally, glucose increases insulin, which has an inhibitory effect on ALAS1 by both decreasing transcription and inhibiting the activity of PGC1α, a transcriptional coactivator that increases transcription of ALAS1. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

The AHPs and hepatic heme regulation. The 4 AHPs are AIP, VP, HCP, and ADP, which result from pathogenic variants in HMBS, PPOX, CPOX, and ALAD, respectively. ALAS1 is the first and rate-limiting step of heme synthesis. The induction of ALAS1 is responsible for the acute neurovisceral attacks of AHP and the accumulation of the neurotoxic intermediates ALA and PBG. Givosiran is an RNA interference medication that targets hepatic ALAS1, decreasing the levels of the ALAS1 enzyme. Hemin is intravenous heme that exerts its effect by negative feedback on ALAS1. Additionally, glucose increases insulin, which has an inhibitory effect on ALAS1 by both decreasing transcription and inhibiting the activity of PGC1α, a transcriptional coactivator that increases transcription of ALAS1. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

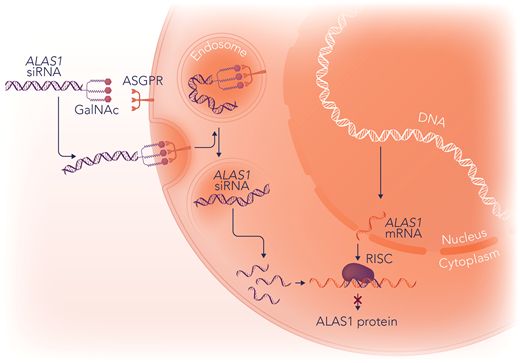

Givosiran is a novel therapeutic agent approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2019 for the treatment of AHP based on the positive results of a phase 3 clinical trial demonstrating a decrease in the acute attack rate and a reduction in urinary PBG and ALA.2 It is a subcutaneously administered RNA interference (RNAi) therapy that targets and degrades the messenger RNA (mRNA) of hepatic ALAS1.2 The trivalent N-acetylgalactosamine ligands of givosiran bind the asialoglycoprotein (ASGPR) receptors of hepatocytes, accounting for its liver specificity (Figure 2).2

The mechanism of action of givosiran. Givosiran is an RNAi medication that inhibits ALAS1 in the liver. Givosiran is conjugated to N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNac), which mediates its targeting to hepatocytes. The ASGPR transmembrane receptors on hepatocytes have high affinity and specificity for GalNac. After binding to ASGPR receptors, givosiran is brought into endolysosomes, where the GalNac ligand is rapidly degraded. Givosiran's double-stranded ALAS1 small interfering RNA (ALAS1-siRNA) molecule is released into the cytosol, where it is cleaved by the enzyme dicer into slightly shorter double-stranded fragments of approximately 20 base pairs and separated into single-stranded RNAs, a passenger (sense) strand and guide (antisense) strand. The passenger strand is degraded, and the guide strand binds to cellular ALAS1-mRNA and is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). RISC then cleaves the new double-stranded RNA, resulting in a decrease in the amount of ALAS1 enzyme. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

The mechanism of action of givosiran. Givosiran is an RNAi medication that inhibits ALAS1 in the liver. Givosiran is conjugated to N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNac), which mediates its targeting to hepatocytes. The ASGPR transmembrane receptors on hepatocytes have high affinity and specificity for GalNac. After binding to ASGPR receptors, givosiran is brought into endolysosomes, where the GalNac ligand is rapidly degraded. Givosiran's double-stranded ALAS1 small interfering RNA (ALAS1-siRNA) molecule is released into the cytosol, where it is cleaved by the enzyme dicer into slightly shorter double-stranded fragments of approximately 20 base pairs and separated into single-stranded RNAs, a passenger (sense) strand and guide (antisense) strand. The passenger strand is degraded, and the guide strand binds to cellular ALAS1-mRNA and is incorporated into the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). RISC then cleaves the new double-stranded RNA, resulting in a decrease in the amount of ALAS1 enzyme. Professional illustration by Somersault18:24.

Pathophysiology and Natural History of AHP

Approximately 80% of heme is produced in the bone marrow by developing erythroid cells, and 20% is produced in the liver for use in hemoproteins such as cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes.3 Enzymatic deficiencies in the hepatic compartment are responsible for the pathogenesis of AHP, as demonstrated by the fact that liver transplantation is curative.4 ADP, for which it is unclear to what extent hepatic vs erythroid heme production is responsible for symptoms, is the exception. In AHP, heme production in the liver may vary substantially due to the inducibility of ALAS1, and factors associated with AHP attacks either directly or indirectly increase ALAS1 transcription by increasing the demand for heme or CYP production. Such factors include caloric restriction, alcohol use, smoking, stress, certain medications, acute illnesses, and progesterone related to the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.1,3,5

Although the name “acute hepatic porphyria” suggests a disease of acute attacks, many patients also have chronic symptoms that contribute to the burden of disease and impair quality of life.6 Patients with AHP are also at increased risk of chronic kidney disease, hypertension, and hepatocellular carcinoma.7,8

AHP management

Management options for AHP include fluids, electrolyte repletion, glucose, pain control, hemin, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogs, givosiran, and avoidance of triggers such as harmful drugs (Table 1).5

Glucose exerts its effect by indirectly inhibiting PGC1α, a transcriptional coactivator that increases ALAS1 transcription.5 Because of this effect, glucose can be used as an initial therapy for AHP attacks if hemin is not immediately available.5

Hemin is a human blood derivative that represses the synthesis of hepatic ALAS1 by negative feedback and remains the standard of care for the management of AHP attacks.9-16 Typically, acute attacks are treated with hemin at 3 to 4 mg/kg/d for at least 4 days. Panhematin, the formulation of hemin available in the United States and many other countries, should be dissolved in albumin to decrease the risk of phlebitis, and if prepared in this way, Panhematin can be administered through a peripheral vein. Treatment with hemin may also be complicated by transient coagulopathy and iron overload, especially if given repeatedly.3,15 During acute attacks, patients may require opiate analgesics, electrolyte repletion, and other therapies for symptoms such as nausea.13,14 Alternative explanations for symptoms should be explored and any potential AHP triggers stopped.

Givosiran randomized clinical trials

Because AHP symptoms are mediated by the induction of hepatic ALAS1, this enzyme was a logical target for drug development (Figure 2).17 A phase 1/2 clinical trial was published in 2019 supporting the use of ALAS1 RNAi in patients with AIP.18 Patients with and without recurrent attacks (defined as ≥2 attacks within 6 months), 17 and 23 participants, respectively, were given various doses of givosiran at different time intervals.18 The 17 AIP patients with recurrent attacks received monthly or quarterly placebo or givosiran, either 2.5 mg/kg or 5 mg/kg subcutaneously, over 12 weeks. The 6 AIP patients with recurrent attacks who received monthly givosiran experienced a 79% reduction in median attack rate and a reduction in urinary ALA, urinary PBG, and urine and serum exosomal ALAS1 mRNA over 12 weeks.18 Those without recurrent attacks were studied primarily for the optimization of givosiran dosing. There were no significant safety signals. One patient with recurrent attacks and a complex medical history who was receiving 5 mg/kg of givosiran monthly died of hemorrhagic pancreatitis during the study. It was deemed at the time to be unlikely related to givosiran, though pancreatitis is now considered a potential complication of givosiran and was recently added to the package label.18

The phase 3 ENVISON trial was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial conducted between 2017 and 2018 and included 94 patients with AHP.2 Patients were included if they were aged 12 years or older, had urine ALA and PBG levels greater than 4 times the upper limit of normal (ULN) at the time of screening, and had experienced 2 porphyria attacks involving hospitalization, urgent care, or home hemin within the 6 months prior to enrollment.2 Though patients were required to stop prophylactic hemin prior to enrollment, investigators were able to treat breakthrough AHP attacks with hemin during the study period. Participants received givosiran at 2.5 mg/kg or placebo subcutaneously monthly for 6 months.2 Among participants, 89% were female, and 95% had AIP. Among the 89 participants with AIP, there was a 74% reduction in the mean annualized attack rate (12.4 vs 3.2), which was the study's primary end point (Table 2).2 As for secondary end points, givosiran was associated with an 86% decrease in median urinary ALA (23.2-4.0 mmol/mole creatinine), a 91% decrease in median urinary PBG (35.1-4.4 mmol/mole creatinine), and a 77% decrease in mean days of hemin use (29.7-6.8 days), all with P < .001.2 The worst daily pain score was lower in the givosiran group (P = .046), but there was no change in the worst daily scores for fatigue or nausea.2 Quality-of-life scores indicated a positive effect on quality of life.

Adverse events were reported in 90% of patients in the givosiran group and 80% of the placebo group, including serious adverse events in 21% of the givosiran group and 9% of the placebo group.2 Adverse events reported more commonly in patients treated with givosiran included nausea, injection-site reactions, rash, fatigue, increased alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and increased creatinine. An ALT level of more than 3 times the ULN occurred in 15% of patients in the givosiran group and 2% in the placebo group.2 One patient in the givosiran treatment group permanently discontinued therapy because of the elevation of ALT to 9.9 times the ULN, which subsequently returned to normal 6 months after discontinuing therapy.2 In other patients with ALT abnormalities, the elevations occurred around 3 to 5 months after starting treatment and resolved with continued therapy or after a brief interruption in therapy.2 Abnormal renal function occurred at a median of 3 months of therapy in 15% of patients on givosiran and 7% of placebo and generally resolved with continued dosing.2

Givosiran long-term data and other givosiran trial data

After the completion of the phase 3 ENVISION study, an open-label extension (OLE) was conducted in which all patients received givosiran of 2.5 or 1.25 mg/kg monthly for 6 months or more before transitioning to 2.5 mg/kg for a total of 36 months.19,20 Of the 94 patients enrolled in ENVISION, 79 completed the OLE.20 The median annualized attack rate (AAR) decreased by 92% in the placebo crossover group. The AAR and the annualized days of hemin use for those on givosiran were both 0.4.20 In the final 3 months of the OLE, 86% and 96% of participants in the continuous givosiran group and placebo crossover groups, respectively, experienced 0 attacks.20 At 36 months follow-up, patients had sustained reductions in ALA and PBG and sustained improvements in quality of life.20 Participants with a history of prophylactic hemin use prior to the phase 3 trial had similar outcomes as those without prophylactic hemin use.20 Adverse events were similar to the phase 3 trial ENVISION (Table 2).20 Notably, 3% of patients had treatment-emergent low-titer antigivosiran antibodies without an effect on drug efficacy.20

Because of the concern that hepatic ALAS1 inhibition may lead to medication interactions due to hepatic CYP depletion, a drug-drug interaction study was performed in patients with AIP who were not having porphyria attacks.21 In these patients, 1 dose of givosiran was associated with a moderate effect on the metabolism of drug substrates for CYP1A2 and CYP2D6 substrates, a weak effect on CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 substrates, and no effect on CYP2C9 substrates, suggesting that clearance of some CYP substrates may be impaired after a single dose of givosiran but that marked depletion of hepatic heme is unlikely.21 In AHP patients on both givosiran and CYP2D6/CYP1A2 substrates with a narrow therapeutic index, close monitoring may be needed.

A post-hoc analysis of the ENVISION phase 3 data was performed to better understand the effect of givosiran on the disease burden in AHP.22 At baseline, opioids were used on most days between attacks by 29% of subjects.22 In the givosiran treatment group, opioid use decreased by 12% during attacks and 13% between attacks, with decreases observed both in those with prior hemin prophylaxis and those without.22 Moreover, those in the givosiran group had 50% fewer days with severe pain between attacks vs placebo.22

Homocysteine elevation and givosiran

After the phase 3 trial, investigators noted that patients on givosiran experienced substantial elevations of plasma homocysteine, and this was confirmed by post-hoc measurements of homocysteine levels from samples collected during ENVISION.23-26 Patients with AHP may have elevated homocysteine levels at baseline, but this data demonstrated that givosiran can exacerbate this phenomenon.23 The mechanism by which AHP and givosiran lead to homocysteine elevation is uncertain but is thought to involve the development of B6 and/or heme deficiency.23 B6 is deficient in almost half of all AHP patients, possibly because B6 is a cofactor for ALAS1, whose activity is elevated in AHP.26 Because both heme and vitamin B6 are cofactors for cystathionine β-synthase, the enzyme that forms cystathionine from homocysteine, their depletion in AHP and/or with givosiran may explain the observed homocysteine elevation in these patients.26 The significance of homocysteine elevation in AHP and with givosiran is unclear. Homocysteine elevation was not associated with efficacy or other safety measures in ENVISION, and studies have demonstrated large interpatient and between-day intrapatient variation.23,26 However, thromboembolism, vascular disease, pancreatitis, and renal dysfunction have been associated with elevated homocysteine levels in patients without AHP, and the clinical significance of elevated homocysteine levels in patients with AHP requires further investigation.26

Real-world givosiran case studies and management

Postmarketing case reports and case series describing real-world experience with givosiran are limited.14,27-29 One case series from France demonstrated a therapeutic benefit when givosiran was started early in a patient's disease course.27 In this study ALT elevations were reported in 32% of patients, including 2 with elevations 4 to 5 times the ULN, which all improved with continued dosing.27 Elevations in homocysteine occurred in all patients, with a median of 117 µmol/L (range, 18.4-573; ULN, 10.7), representing an increase from baseline in all who had laboratory values prior to starting givosiran.27 Vitamin B6 improved but did not normalize homocysteine levels.25-27 A moderate initial increase in creatinine was seen in 91% of patients, which was transient.30

Additional case reports have described patients in which givosiran was initially associated with an improvement in symptoms and a reduction in urinary ALA and PBG, only for patients to have a subsequent symptom recrudescence despite continued normalization of ALA and PBG.14,29 Although ALA has traditionally been considered the neurotoxic intermediate primarily responsible for AHP symptoms, the observations of discordantly low ALA and symptoms in patients on givosiran are poorly understood. This may suggest an alternative mechanism of attacks that is not entirely dependent on ALA accumulation, such as neuronal heme deficiency.14,31

Starting givosiran

The optimal time to start givosiran in a patient's disease course is not well-defined. As noted earlier, the ENVISON trial only included patients who had experienced more than 2 attacks in the 6 months prior to enrollment. However, data supporting givosiran use in other types of patients are lacking, such as patients with 1 life-threatening attack or rare attacks despite chronic symptoms impairing quality of life.2,6,14,32 Whether givosiran can be used to treat acute attacks has not been studied, although a decrease in urinary PBG and ALA within hours of dosing suggests that it would be effective in the acute setting.33 Moreover, it is unknown whether givosiran is safe in pregnant or lactating women despite being a disease that primarily affects women of reproductive age.

Givosiran in VP, HCP, and ADP

While neurovisceral symptoms are unifying features that can be present in any AHP, patients with VP and, less commonly, with HCP can experience chronic, blistering cutaneous photosensitivity.14 Whether givosiran is helpful for these cutaneous symptoms is not known. VP and HCP patients composed only 5 out of 94 patients in the ENVISION study and were not included in the statistical analysis for end points, though their response to treatment was consistent with AIP patients.2

ADP is a rare type of AHP that is inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion, with fewer than 10 cases reported to date, all in males.34 Givosiran use was reported in one ADP patient without improvement in symptoms or in urine ALA levels, which suggests that both hepatic and erythropoietic ALAD deficiencies contribute to the accumulation of porphyrins and porphyrin precursors in ADP.34

Management of patients on givosiran

In our patients we monitor complete blood counts, liver biochemistries, kidney function, urine ALA, urine PBG, and homocysteine prior to each givosiran injection. These data are useful in identifying the common side effects of givosiran and evaluating biochemical responses to treatment. Patients are also queried about symptoms and quality of life at each visit. In patients who develop side effects, we consider dose adjustments, dose pauses, and/or referrals to our multidisciplinary team, which includes hepatology and nephrology. For patients with elevated homocysteine levels, we prescribe 100 mg/d of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine).

Further, as patients with AHP have a higher risk of HCC than the general population (adjusted hazard ratio, ~38), we begin screening for HCC at 6-month intervals in all patients over the age of 50, regardless of treatment with givosiran.7 It remains unknown whether givosiran has an effect on the risk of long-term complications of AHP such as HCC, chronic kidney disease, and hypertension.

Patients on givosiran may still have acute attacks, and these attacks should be treated with hemin while continuing monthly givosiran.2 As for all patients with AHP, alternative causes for acute symptoms should be considered. For patients with persistent symptoms and elevated levels of urinary PBG and ALA despite standard givosiran dosing, we consider increasing the dose or frequency of this medication. As noted above, urine ALA and PBG levels may not be elevated in AHP attacks for patients on givosiran, and in this setting, attacks should be diagnosed based on patient symptoms, while being sure to exclude alternative causes, rather than relying on biochemical markers.14,29 New therapies such as PBG mRNA and gene therapy are currently in development and hold promise for patients with AHP.35-39 The role these therapies will play in the AHP treatment paradigm is currently unclear.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

The patient experienced mild elevations in liver biochemistries while on givosiran. She was evaluated by hepatology for alternative causes, with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease a likely alternative explanation. Her urine ALA and PBG remain suppressed, and while on givosiran she has only experienced minor symptoms that have not required hemin. Despite having been on givosiran 2.5 mg/kg monthly for years, after recent doses of givosiran she developed a rash that improved with antihistamine premedication.

Conclusion

Givosiran is a life-changing therapy that leads to decreased AHP attack rates and improved quality of life in patients with AHP. However, much information remains unknown, such as the long-term effects of this therapy on disease burden and AHP complications, when to initiate therapy, and how to effectively manage patients with breakthrough symptoms. Givosiran has revolutionized the management of AHP, and we look forward to future studies to further elucidate the role and impact of this important therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Karl Anderson for his critical review of the article.

Amy K. Dickey receives funding from a National Institutes of Health (NIH) NIAMS K23 grant 1K23AR079586. Dr. Dickey and Rebecca K. Leaf are members of the Porphyrias Consortium (PC). The PC is part of the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network, which is funded by the NIH and led by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) through its Division of Rare Diseases Research Innovation. The PC is funded under grant number U54DK083909 as a collaboration between NCATS and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Amy K. Dickey: consultancy: Alnylam Pharma, Recordati Pharma; research funding: Disc Medicine.

Rebecca K. Leaf: consultancy: Alnylam Pharma, Recordati Pharma; research funding: Disc Medicine.

Off-label drug use

Amy K. Dickey: The use of hemin for prophlaxis of AHP symptoms is off-label.

Rebecca K. Leaf: The use of hemin for prophlaxis of AHP symptoms is off-label.