Abstract

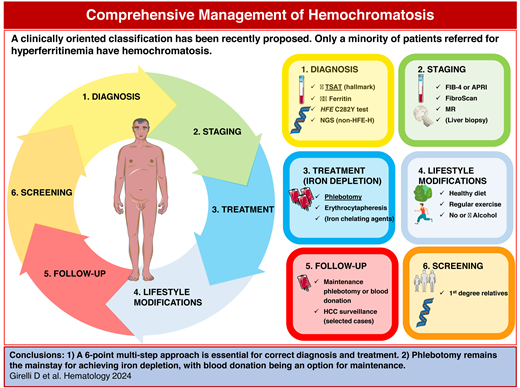

The term hemochromatosis refers to a group of genetic disorders characterized by hepcidin insufficiency in the context of normal erythropoiesis, iron hyperabsorption, and expansion of the plasma iron pool with increased transferrin saturation, the diagnostic hallmark of the disease. This results in the formation of toxic non–transferrin-bound iron, which ultimately accumulates in multiple organs, including the liver, heart, endocrine glands, and joints. The most common form is HFE-hemochromatosis (HFE-H) due to p.Cys282Tyr (C282Y) homozygosity, present in nearly 1 in 200 people of Northern European descent but characterized by low penetrance, particularly in females. Genetic and lifestyle cofactors (especially alcohol and dysmetabolic features) significantly modulate clinical expression so that HFE-H can be considered a multifactorial disease. Nowadays, HFE-H is mostly diagnosed before organ damage and is easily treated by phlebotomy, with an excellent prognosis. After iron depletion, maintenance phlebotomy can be usefully transformed into a blood donation program. Lifestyle changes are important for management. Non-HFE-H, much rarer but highly penetrant, may lead to early and severe heart, liver, and endocrine complications. Managing severe hemochromatosis requires a comprehensive approach optimally provided by consultation with specialized centers. In clinical practice, a proper diagnostic approach is paramount for patients referred for hyperferritinemia, a frequent finding that reflects hemochromatosis only in a minority of cases.

Learning Objectives

Recognize clinical and biochemical hallmarks of hereditary hemochromatosis

Assess the risk of organ damage in hereditary hemochromatosis and set appropriate staging, treatment, follow-up, and familiar screening

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 56-year-old Caucasian man presented to the general practitioner for fatigue experienced over the last few months. His family and past medical history were unremarkable. The physical examination showed mild hepatomegaly but no skin discoloration, scleral jaundice, edema, splenomegaly, or ascites. He did not take any medication or illicit drugs; his alcohol intake was moderate (1 to 2 drinks daily). No other risk factor for liver disease was apparent. His lifestyle was sedentary, and his body mass index was 25.3 kg/m2. Initial blood tests showed a normal complete blood count (hemoglobin [Hb] level, 15.9 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume, 98 fL), C-reactive protein, AST, albumin level, glucose level, and prothrombin time. Hyperferritinemia (890 µg/L; normal value <300) and mildly increased ALT (46 U/L; normal value <40) were noted. The patient was referred to our center for a suspected iron overload (IO) disorder.

Introduction—hemochromatosis definition and classification

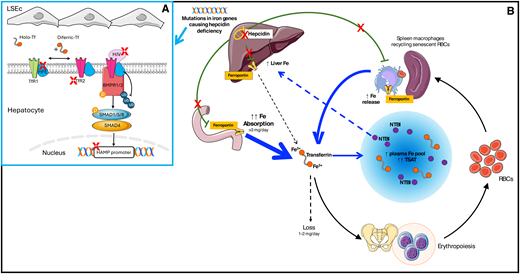

The discovery of hepcidin at the beginning of this century was a turning point in understanding iron homeostasis disorders.1,2 Nowadays, the term hemochromatosis is reserved for a group of genetically determined IO disorders sharing the common pathophysiology of insufficient hepcidin production or activity in the absence of a primary red blood cell disorder.3 This specification is important to distinguish hemochromatosis from other disorders due to hepcidin suppression by factors released during ineffective erythropoiesis, like non–transfusion-dependent thalassemias or myelodysplastic syndromes.3-5 The liver hormone hepcidin physiologically maintains body iron content in the optimal range of 3 to 4 g by negatively modulating ferroportin, the main cellular iron exporter.2 Insufficient ferroportin inhibition in duodenal enterocytes leads to lifelong hyperabsorption of dietary iron that accumulates as humans lack mechanisms for excreting excess iron. Central to the pathogenesis of hemochromatosis is the expansion of the plasma iron pool, also due to the uncontrolled release by macrophages (Figure 1), resulting in increased transferrin saturation (TSAT). Values above 45% to 50% represent a diagnostic hallmark, far more than hyperferritinemia. Exceeding the transferrin-binding capacity promotes the formation of non–transferrin-bound iron, which is avidly taken up by hepatocytes, cardiomyocytes, and endocrine cells,6 where it causes damage likely through oxidant stress and/or ferroptosis.7

Pathophysiology of hemochromatosis. (A) Hepcidin production by hepatocytes is feedback-regulated by iron through complex multimolecular pathways. Interaction between BMPs (especially BMP2 and BMP6) produced by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC) and BMP receptors 1-2 is the main pathway controlling basal hepcidin production. Hemojuvelin is a BMP coreceptor. High Fe (HFE) and transferrin receptor 2 (TFR2) participate in iron sensing and modulate the response to increased circulating iron. For a comprehensive review, see Galy et al.9 Mutations in heterogenous genes (red X) lead to hepcidin deficiency (B). Iron hyperabsorption and excess iron release from macrophages expand the plasma iron pool (blue arrows) with the formation of toxic non-transferrin-bound iron (NTBI), which accumulates in the liver and other organs. Fe, iron; RBC, red blood cell.

Pathophysiology of hemochromatosis. (A) Hepcidin production by hepatocytes is feedback-regulated by iron through complex multimolecular pathways. Interaction between BMPs (especially BMP2 and BMP6) produced by liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSEC) and BMP receptors 1-2 is the main pathway controlling basal hepcidin production. Hemojuvelin is a BMP coreceptor. High Fe (HFE) and transferrin receptor 2 (TFR2) participate in iron sensing and modulate the response to increased circulating iron. For a comprehensive review, see Galy et al.9 Mutations in heterogenous genes (red X) lead to hepcidin deficiency (B). Iron hyperabsorption and excess iron release from macrophages expand the plasma iron pool (blue arrows) with the formation of toxic non-transferrin-bound iron (NTBI), which accumulates in the liver and other organs. Fe, iron; RBC, red blood cell.

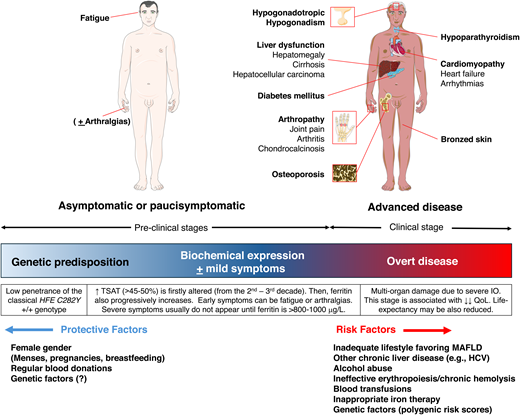

Table 1 shows the classification of hemochromatosis proposed by the International BIOIRON Society in 2022, now universally adopted.8 Apart from the genes encoding the key players of the hepcidin/ferroportin axis (HAMP and SLC40A1), HFE and TFR2 encode membrane proteins involved in sensing iron levels for homeostatic hepcidin regulation. HJV encodes a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) coreceptor (Figure 1). The exact molecular mechanisms underlying hepcidin regulation are still incompletely understood (reviewed elsewhere).9 All hemochromatosis forms are autosomal recessive, except for dominant ultrarare gain-of-function SLC40A1 mutations leading to hepcidin resistance, which functionally recapitulates hepcidin deficiency. SLC40A1 loss-of-function mutations cause ferroportin disease, a distinct disorder characterized by normal TSAT, predominant macrophage iron accumulation, and low to normal Hb levels, possibly resulting in poor phlebotomy tolerance.3,10 In hemochromatosis, conversely, macrophages are generally iron-poor due to uncontrolled ferroportin release.10 The most common hemochromatosis form is, by far, HFE related due to homozygosity for the p.Cys282Tyr (C282Y) variant of Celtic origin,7 present in more than 80% of patients of Northern European descent. The other forms are rare and collectively designed as “non-HFE.” The clinical manifestations are common to all hemochromatosis types but vary from asymptomatic mild elevation of iron tests to multiorgan failure (Figure 2). This is mainly related to the penetrance of the genetic defect, minimal in HFE and maximal in HJV and HAMP (also called “juvenile” forms). The C282Y disrupts a cysteine bond on the HFE protein, preventing its membrane localization. This blunts hepcidin response to increased serum iron, but hepcidin baseline levels are only slightly reduced or inappropriately normal.11 This mild defect explains the long-delayed onset of HFE-H so that only a minority of C282Y homozygotes, prevalently males after the fourth through sixth decade, develop a clinical disease. The testosterone inhibition of hepcidin also likely contributes to the different gender penetrance.12 Iron losses with menses generally protect females until menopause. HFE-H resembles a multifactorial rather than a monogenic disorder. Acquired cofactors like alcohol and hepatitis C virus, which both inhibit hepcidin synthesis, as well as other causes of liver morbidity, especially metabolic-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), amplify the genetic defects.12 As MAFLD is estimated to affect approximately 25% of the world's adult population,13 the coexistence with HFE-H is anything but rare, underscoring the relevance of lifestyle modification. Genetic modifiers also play a role. A recent analysis from the UK Biobank (including 2890 C282Y homozygotes) has shown a significant contribution of a polygenic risk score built up with common polymorphisms in many iron-regulating genes.14 The risk of developing clinically relevant IO in subjects with the relatively common C282Y/H63D HFE genotype is exceedingly low unless cofactors clearly predominate.3,7,8

Clinical manifestations and cofactors influencing the penetrance of HFE-hemochromatosis. Most patients are now diagnosed in the early phase before the development of organ damage-related symptoms. Heart and endocrine manifestations are often the presenting symptoms in severe (juvenile) non-HFE hemochromatosis forms. They can also be seen in patients with severe HFE- hemochromatosis and substantial cofactors burden,34 but they are now exceedingly rare. HCV, hepatitis C virus; QoL, quality of life.

Clinical manifestations and cofactors influencing the penetrance of HFE-hemochromatosis. Most patients are now diagnosed in the early phase before the development of organ damage-related symptoms. Heart and endocrine manifestations are often the presenting symptoms in severe (juvenile) non-HFE hemochromatosis forms. They can also be seen in patients with severe HFE- hemochromatosis and substantial cofactors burden,34 but they are now exceedingly rare. HCV, hepatitis C virus; QoL, quality of life.

BIOIRON classification of hemochromatosis

| . | Gene/mutations . | Molecular diagnosis . | Clinical features . | Pathophysiology . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFE-H | HFE (High Fe) | First-level genetic test for C282Y (widely available) | Common In populations of Northern European descent Low penetrance, often requiring cofactors. Adults, typically after the fourth-sixth decades, predominantly in males | Mild hepcidin deficiency, with blunted feedback response to increasing plasma Fe. Hepcidin level mildly reduced or inappropriately normal for iron stores. |

| Non–HFE-H | HJV (hemojuvelin) HAMP (hepcidin) TFR2 (transferrin receptor 2) SLC40A1 (ferroportin)a Digenic inheritance possible (PIG-A)b (other still unknown) | Second-level genetic test (NGS panel looking for “private” mutations in iron genes) available at referral centers and requiring expert interpretation | Rare or ultrarare Any population High penetrance (negligible role for cofactors) Juvenile onset (esp. HJV and HAMP) Both sexes equally affected Heart and endocrine complications often predominant (esp. HJV and HAMP) | Severe hepcidin deficiency (or, rarely, hepcidin resistance in gain-of-function SLC40A1 mutations). Hepcidin levels very low to undetectable (increased in hepcidin resistance). |

| . | Gene/mutations . | Molecular diagnosis . | Clinical features . | Pathophysiology . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HFE-H | HFE (High Fe) | First-level genetic test for C282Y (widely available) | Common In populations of Northern European descent Low penetrance, often requiring cofactors. Adults, typically after the fourth-sixth decades, predominantly in males | Mild hepcidin deficiency, with blunted feedback response to increasing plasma Fe. Hepcidin level mildly reduced or inappropriately normal for iron stores. |

| Non–HFE-H | HJV (hemojuvelin) HAMP (hepcidin) TFR2 (transferrin receptor 2) SLC40A1 (ferroportin)a Digenic inheritance possible (PIG-A)b (other still unknown) | Second-level genetic test (NGS panel looking for “private” mutations in iron genes) available at referral centers and requiring expert interpretation | Rare or ultrarare Any population High penetrance (negligible role for cofactors) Juvenile onset (esp. HJV and HAMP) Both sexes equally affected Heart and endocrine complications often predominant (esp. HJV and HAMP) | Severe hepcidin deficiency (or, rarely, hepcidin resistance in gain-of-function SLC40A1 mutations). Hepcidin levels very low to undetectable (increased in hepcidin resistance). |

The main features of HFE—and non-HFE-H—are illustrated. Decreased production of hepcidin is the common pathophysiological background.

Rare gain-of-function mutations in the gene encoding ferroportin (SLC40A1) give rise to a decreased hepcidin effect because of ferroportin resistance. Loss-of-function SLC40A1 mutations lead to ferroportin disease, a distinct disorder.3

Recently, a new pediatric form of iron overload due to constitutional PIGA (phosphatidylinositol glycan anchor biosynthesis class A) mutations affecting membrane binding of hemojuvelin has been described.40At variance with hemochromatosis, it is mainly characterized by neurologic dysfunction.40 In rare cases of hemochromatosis no mutation is found in the listed genes, indicating the role of still unknown gene(s).

Fe, iron.

Adapted from Girelli et al.3

At the opposite end of the spectrum, HJV (and HAMP) mutations impair the major regulatory axis, resulting in very low to undetectable hepcidin levels (Table 1). In general, non-HFE hemochromatosis is characterized by high penetrance in both genders with minimal or no influence by cofactors, early onset (second through third decade for HJV and HAMP, third through fourth for TFR2), and predominant hypogonadism and heart failure.15,16 Consanguinity is not infrequent, and mutations are distributed worldwide. Due to genetic heterogeneity, digenic inheritance is possible, and some cases remain molecularly undefined after extensive next-generation sequencing (NGS) analyses.3

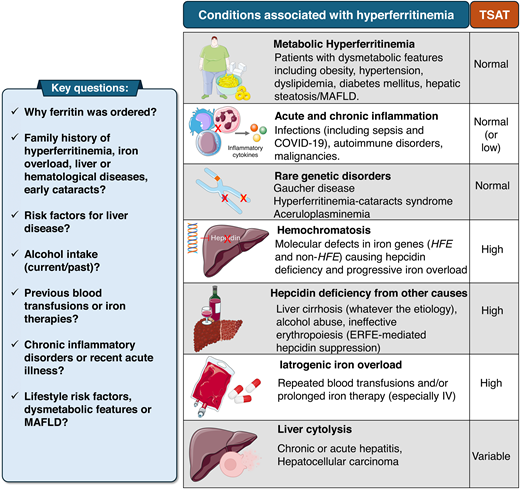

How to approach hyperferritinemia

This middle-aged man presented with mild nonspecific symptoms and hyperferritinemia, a common cause of hematological consultation with a wide differential diagnosis.17 Ferritin can increase because of inflammation, cytolysis, and several inherited or acquired metabolic alterations.18,19 Only a minority of patients have a true IO disorder. The differential diagnosis is based on clinical history and the measurement of TSAT.3,4,17 Metabolic hyperferritinemia (MHF, according to a recent consensus statement) is by far the most common cause in daily practice.20 TSAT is typically normal, and the patient shows 1 or multiple dysmetabolic features, including MAFLD (Figure 3).21 The pathogenesis of MHF is complex and incompletely understood, likely reflecting subtle alterations of iron trafficking and/or inflammation,20 with poor correlation with histologically proven liver iron deposits.22 No clear benefit for iron depletion has been demonstrated. Rather, as MHF is consistently associated with the risk of cardiovascular complications (particularly if ferritin is >500 mg/L), lifestyle amelioration is mandatory and often reduces ferritin.22 Patients with the triad high ferritin/normal TSAT/absence of dysmetabolic features fall in the category of “unexplained hyperferritinemia” related to rare disorders and should be referred to specialized centers.3,23

Approach to the patient referred for hyperferritinemia. Most patients do not have IO or hemochromatosis. The differential diagnosis relies on clinical history and TSAT measurement. The most common cause in clinical practice is (MHF, reviewed in Valenti et al20), typically with normal TSAT, frequently observed in individuals with 1 or more dysmetabolic features.

Approach to the patient referred for hyperferritinemia. Most patients do not have IO or hemochromatosis. The differential diagnosis relies on clinical history and TSAT measurement. The most common cause in clinical practice is (MHF, reviewed in Valenti et al20), typically with normal TSAT, frequently observed in individuals with 1 or more dysmetabolic features.

In the index case, elevated TSAT (88%) indicated HFE-H as the likely diagnosis. The first-level genetic test confirmed C282Y homozygosity.

Management of hemochromatosis

Staging

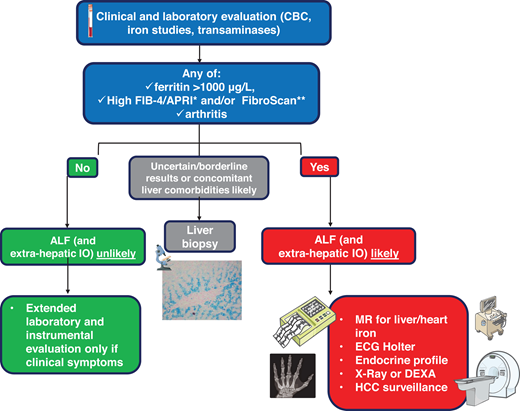

Appropriate staging is crucial after the diagnosis of hemochromatosis. Nowadays, most patients are diagnosed in an early or preclinical phase due to increased awareness and iron studies prescribed during “routine” analyses (Figure 2).24 Except for the rare “juvenile” forms, hemochromatosis is generally a mild disease with an excellent prognosis. Advanced liver fibrosis (ALF) or cirrhosis implies a less favorable prognosis and the need for surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) even after iron depletion.4,23 Tools for staging are summarized in Figure 4. Arthropathy and/or ferritin levels higher than 1000 mg/L can be informative, being associated with ALF.4,23,25 Noninvasive tools recently proposed include FibroScan and simple scores like FIB-4/APRI but require validation in large cohorts.4,23

Hemochromatosis staging. Predicting the presence of ALF is important since it increases the risk of HCC and requires adequate surveillance. Noninvasive tools include APRI (aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index) and FIB-4 (patient age, platelet count, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine aminotransferase) scores, and FibroScan (measuring liver stiffness through transient elastography).4,8,23 A liver biopsy is rarely performed in uncertain cases. Extrahepatic complications should be properly investigated in patients with ascertained or likely ALF. The endocrine profile should include follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), testosterone, or estrogens, looking at possible hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, especially in juvenile forms. CBC, complete blood count; DEXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, measuring bone mineral density; ECG, electrocardiogram.

Hemochromatosis staging. Predicting the presence of ALF is important since it increases the risk of HCC and requires adequate surveillance. Noninvasive tools include APRI (aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index) and FIB-4 (patient age, platelet count, aspartate aminotransferase, and alanine aminotransferase) scores, and FibroScan (measuring liver stiffness through transient elastography).4,8,23 A liver biopsy is rarely performed in uncertain cases. Extrahepatic complications should be properly investigated in patients with ascertained or likely ALF. The endocrine profile should include follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), testosterone, or estrogens, looking at possible hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, especially in juvenile forms. CBC, complete blood count; DEXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, measuring bone mineral density; ECG, electrocardiogram.

Magnetic resonance is widely used to estimate liver iron content and iron in the heart and pancreas.3,4 Different algorithms based on signal alteration induced by ferromagnetic iron are used according to local equipment and expertise.26 A liver biopsy is now reserved for cases with equivocal results after noninvasive evaluations. Extrahepatic complications should be searched in patients with advanced disease or symptoms suggesting organ damage.

We did not perform further evaluations in our patient with a ferritin level lower than 1000 mg/L, no symptoms, and reassuring tests for ALF (FIB-4 score and FibroScan).

Iron-depletion therapy

Notwithstanding the advance in hemochromatosis' pathophysiology, phlebotomy that mobilizes iron for erythropoiesis remains the mainstay of treatment.4,23,27 It is relatively easy, cheap, and highly effective in most patients. The classical induction, maintenance, and monitoring schedules are summarized in Table 2. In the index case, the ferritin target (50 mg/L) was reached after 29 phlebotomies (corresponding to ~4.8 g removed iron). Tolerance was excellent and the fatigue resolved. Note that the patient's high-normal Hb level and mean corpuscular volume values are frequent in HFE-C282Y individuals,3,8,28 reflecting a tendency to sustained erythropoiesis, likely contributing to their unique tolerance of phlebotomies. Maintenance phlebotomy to avoid reaccumulation was 3 per year, with on-target ferritin levels (50-100 mg/L) and normal transaminases. The patient was eventually enrolled as a blood donor according to local protocol.4 The benefits of phlebotomy in hemochromatosis have been systematically reviewed.29 Improved survival was reported in patients adequately phlebotomized.29 Reversal of liver fibrosis and sometimes even cirrhosis is documented,4,23 significantly reducing the long-term risk of HCC.30 Current guidelines suggest that all patients with high ferritin (>200 or >300 mg/L in females and males, respectively), even if asymptomatic, should be treated to prevent progressive iron accumulation.4,23,31 Management during pregnancy should be individualized, but most patients can suspend phlebotomy.4

Treatment of hemochromatosis

| Optimization of: . | Treatment and prevention of: . | Treatment of: . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIFESTYLE . | IRON OVERLOAD . | COMPLICATIONS . | |

| • MINIMIZE OR AVOID ALCOHOL • HEALTHY DIET • REGULAR PHYSICAL ACTIVITY, MAINTAIN IDEAL WEIGHT • AVOID RAW OR UNDERCOOKED SEAFOOD AND WOUND CONTACT WITH SEAWATER | • PHLEBOTOMY | Induction phase 350-500 mL (according to sex/weight) every 1-2 weeks. Check Hb before each phlebotomy (discontinue/delay if <11-12 g/dL) and ferritin every 4 phlebotomies (more frequently when ferritin <200 mg/L). Goal: ferritin ~50 mg/L. Maintenance phase 2-4 phlebotomies per year to keep ferritin within the goal of ~50-100 mg/L. Patients may be usefully enrolled as regular blood donors. Typically well tolerated. Problematic if hemodynamic instability (advanced liver or heart failure), poor venous access, needle phobia, living away from health care facilities. | • LIVER AND HEART FAILURE Erythrocytapheresis preferable over phlebotomy (isovolemic procedure). Deferoxamine in heart failure during the first phases. • HORMONE REPLACEMENT THERAPY (Eg, insulin, androgens) • ARTHROPATHY (May not respond to phlebotomy). Analgesia, physiotherapy, joint replacement • OSTEOPOROSIS Biphosphonates, vitamin D |

| • ERYTHROCYTAPHERESIS | More rapid iron depletion. Cost issues (equipment, personnel). It can preserve blood volume. | ||

| • IRON-CHELATING AGENTSa | Deferoxamine (parenteral), or deferasirox and deferiprone (oral). Use limited to patients with severe life-threatening IO (alone or in combination) or intolerant to phlebotomy. A careful evaluation of the risk-benefit ratio is needed, and they should be prescribed by clinicians with expertise in IO disorders. | ||

| • HEPCIDIN MIMETICS | Rusfertide (weekly SC injections) promising for maintenance phase (needs confirmation). | ||

| Optimization of: . | Treatment and prevention of: . | Treatment of: . | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LIFESTYLE . | IRON OVERLOAD . | COMPLICATIONS . | |

| • MINIMIZE OR AVOID ALCOHOL • HEALTHY DIET • REGULAR PHYSICAL ACTIVITY, MAINTAIN IDEAL WEIGHT • AVOID RAW OR UNDERCOOKED SEAFOOD AND WOUND CONTACT WITH SEAWATER | • PHLEBOTOMY | Induction phase 350-500 mL (according to sex/weight) every 1-2 weeks. Check Hb before each phlebotomy (discontinue/delay if <11-12 g/dL) and ferritin every 4 phlebotomies (more frequently when ferritin <200 mg/L). Goal: ferritin ~50 mg/L. Maintenance phase 2-4 phlebotomies per year to keep ferritin within the goal of ~50-100 mg/L. Patients may be usefully enrolled as regular blood donors. Typically well tolerated. Problematic if hemodynamic instability (advanced liver or heart failure), poor venous access, needle phobia, living away from health care facilities. | • LIVER AND HEART FAILURE Erythrocytapheresis preferable over phlebotomy (isovolemic procedure). Deferoxamine in heart failure during the first phases. • HORMONE REPLACEMENT THERAPY (Eg, insulin, androgens) • ARTHROPATHY (May not respond to phlebotomy). Analgesia, physiotherapy, joint replacement • OSTEOPOROSIS Biphosphonates, vitamin D |

| • ERYTHROCYTAPHERESIS | More rapid iron depletion. Cost issues (equipment, personnel). It can preserve blood volume. | ||

| • IRON-CHELATING AGENTSa | Deferoxamine (parenteral), or deferasirox and deferiprone (oral). Use limited to patients with severe life-threatening IO (alone or in combination) or intolerant to phlebotomy. A careful evaluation of the risk-benefit ratio is needed, and they should be prescribed by clinicians with expertise in IO disorders. | ||

| • HEPCIDIN MIMETICS | Rusfertide (weekly SC injections) promising for maintenance phase (needs confirmation). | ||

Lifestyle measures are an integral part of the treatment. Patients are often worried about the need to avoid iron-rich foods, particularly red meat. There is no reason to prescribe drastic diets, as iron is ubiquitous in foods.

SC, subcutaneous.

The only clinical manifestation that may not respond to phlebotomy is arthropathy,4 nowadays a major determinant of impaired quality of life.32 Occasionally, it can appear after successful iron depletion and has been associated with prolonged TSAT greater than 50%.23 However, lowering TSAT below 50% is difficult in most patients, even if ferritin is kept near the iron- deficiency range. From a pathophysiology standpoint, it must be remembered that phlebotomy-induced iron deficiency can further aggravate hepcidin deficiency.12 Whether innovative therapeutic approaches with hepcidin agonists (see below) will be useful remains to be determined.

Blood donations

Accepting hemochromatosis individuals as blood donors has long been debated for possible safety and ethical concerns regarding nonaltruistic donation. No real risk in both aspects has ever been demonstrated.33 Current US Food and Drug Administration policies (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=630.15) and most European countries allow blood donation from uncomplicated patients, although statements and applications vary, leaving some discretion at single centers. Some guidelines explicitly support the adoption of “hemochromatosis donor programs.”4 This might counterbalance the lack of motivation to pursue lifelong health care attendance in asymptomatic patients. Moreover, a reverse ethical argument is the possible underutilization of a precious resource in the context of progressively shrinking donations.33

Alternative to phlebotomies

Erythrocytapheresis is an isovolemic procedure that can remove nearly 4-fold more red blood cells than 1-unit phlebotomy, preserving patients' plasma proteins, clotting factors, and platelets and reducing the time frame of the induction phase.4,23 Disadvantages include cost and the need for specialized equipment and staff. A blinded study comparing erythrocytapheresis vs sham treatment (plasmapheresis) in C282Y homozygotes with moderate hyperferritinemia (300-1000 mg/L) showed a significant reduction of fatigue score,31 supporting treatment in paucisymptomatic cases. We use erythrocytapheresis only in selected patients with advanced liver or heart complications with poor tolerance to phlebotomy-induced hypovolemia. Similarly, iron chelators are generally restricted to severe cases, especially with advanced heart failure.4,15,16,23,34 Continuous intravenous deferoxamine has been reported to reverse end-stage heart failure in patients initially listed for transplantation.15 In less severe settings, oral iron chelators can be considered when phlebotomy is problematic (Table 2).4,23

Hepcidin agonists

Rusfertide, a hepcidin mimetic peptide successfully used in polycythemia vera,28 has been recently employed in a proof-of- concept trial enrolling HFE-H patients in the maintenance phase.35 Compared to phlebotomy alone, adding rusfertide reduced the rates of phlebotomy. It also decreased TSAT, which could be advantageous in the long term. A reduced need for attending health care facilities may improve the quality of life, especially in patients living in remote areas. Further studies are needed to corroborate these results and demonstrate cost-effectiveness.36 Rusfertide slows iron absorption and facilitates redistribution but does not induce iron loss. Thus, it is likely useless for the depletion phase.

Lifestyle modifications

Lifestyle measures are integral to the appropriate management of hemochromatosis (Table 2). Being both common in the general population, C282Y homozygosity and MAFLD may coexist. The same may be true for alcohol liver injury. Body weight should be kept normal through regular physical activity and a healthy diet. There is no reason to prescribe drastic diets (eg, devoid of red meat), as iron is ubiquitous in foods. We generally advise a Mediterranean diet with low consumption of meats and processed foods. Alcohol should be avoided in patients with signs of liver disease and during the induction phase, while moderate consumption can be allowed in uncomplicated cases after iron depletion. Attention should be paid to dietary supplements, often containing iron. Patients should avoid raw or undercooked shellfish and contact of wounds with seawater, both possibly contaminated by Vibrio vulnificus, an iron-avid pathogen that may cause life-threatening infections.37 Proton pump inhibitors decrease iron absorption and can reduce the need for phlebotomy when prescribed for other reasons. However, their specific use in hemochromatosis is not recommended.4

Since our patient was overweight, regular physical activity was recommended.

Family screening

Cascade first-degree family screening is indicated whenever hemochromatosis is diagnosed. Due to the low/delayed clinical penetrance, in HFE-H analyses of children can be deferred until late adolescence.4,23 For the same reason, population screening is usually not recommended.4 However, the recent UK Biobank follow-up study has shown increased morbidity (especially osteoarthritis and the need for joint replacement) and a slightly increased mortality in unrecognized older C282Y homozygous males.38 Future guidelines may reconsider this point, at least in Caucasian males after the fifth and sixth decades.23

The index patient had a 62-year-old brother living in a rural area whose test results indicated C282Y homozygosity. His biochemical profile showed ferritin level, 1020 mg/L; TSAT, 78%; and a mild elevation of transaminases. Two years before, he had received a diagnosis of seronegative undifferentiated arthritis with poor response to hydroxychloroquine. A physical examination and plain radiogram showed typical hemochromatosis arthropathy of the hands (Figure 5). The Fib-4 score and FibroScan confirmed the high probability of ALF,25 making a liver biopsy unnecessary. There were no clinical or biochemical signs of other relevant complications. Phlebotomy, surveillance for HCC, and physiotherapy of involved joints were started.

Hemochromatosis arthropathy. Typical bilateral involvement of the metacarpophalangeal joints, especially the second and third, with plain radiogram showing the classical “hook” osteophytes. Hemochromatosis arthropathy can involve multiple other joints, including the hip, ankle, knee, elbow, shoulder, and spine.

Hemochromatosis arthropathy. Typical bilateral involvement of the metacarpophalangeal joints, especially the second and third, with plain radiogram showing the classical “hook” osteophytes. Hemochromatosis arthropathy can involve multiple other joints, including the hip, ankle, knee, elbow, shoulder, and spine.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 27-year-old woman of Greek origin was referred to our center because of marked hyperferritinemia (1340 µg/L) and a moderate elevation of transaminases, performed because of fatigue and the recent onset of shortness of breath during exercise. She also reported oligomenorrhea in the last year. The parents, both in good health, were first cousins. The physical examination showed nuanced skin hyperpigmentation and mild hepatomegaly. Her lungs were clear, and no peripheral edema was evident, ruling out overt heart decompensation. TSAT was 93% and the HFE C282Y negative. An MR T2* scan revealed severe liver and heart IO. A liver biopsy showed grade 4-plus siderosis, especially in periportal hepatocytes and bile duct cells, and mild fibrosis. Iron depletion was immediately started by erythrocytapheresis, which was well tolerated and followed by standard phlebotomy. A total of approximately 5.5 g of iron were removed in the following 6 months. The patient recovered a good exercise tolerance and menses gradually normalized. An in-house NGS iron panel revealed homozygosity for the HJV missense variant p.Gly320Val.39

The diagnosis of non–HFE-H is based on clinical and laboratory elements, and treatment must be prioritized over molecular characterization.3 A comprehensive approach is needed to properly manage non–HFE-H cases, which can be severe or life-threatening. Nevertheless, the prognosis can still be reverted in advanced cases.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Prof. Clara Camaschella for lifelong invaluable mentoring and for critical review of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Domenico Girelli: no competing financial interests to declare.

Giacomo Marchi: no competing financial interests to declare.

Fabiana Busti: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Domenico Girelli: nothing to disclose.

Giacomo Marchi: nothing to disclose.

Fabiana Busti: nothing to disclose.