Abstract

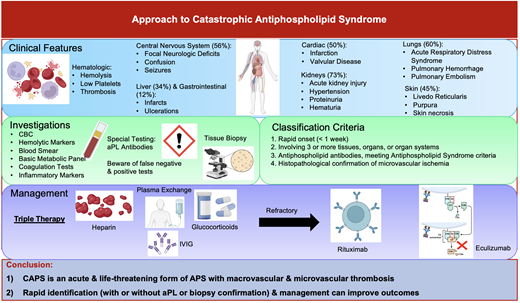

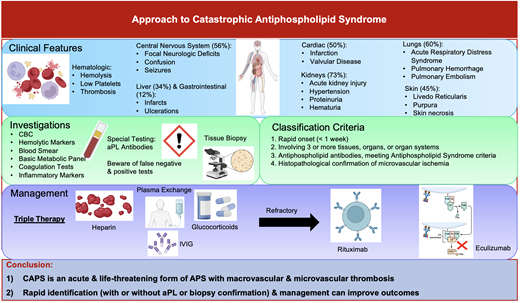

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is a rare but life-threatening form of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) defined by the rapid onset of large and small vessel thrombosis occurring simultaneously across multiple sites, resulting in multiorgan dysfunction. The presence of underlying immune dysfunction causing activation of coagulation and, in many cases, abnormal complement regulation predisposes these patients to thrombotic events. CAPS is often preceded by triggering factors such as infection, surgery, trauma, anticoagulation discontinuation, and malignancy. Given the high mortality rate, which may exceed 50%, prompt recognition and initiation of management is required. The detection of antiphospholipid antibodies and the histopathologic identification of microvascular ischemia via tissue biopsy are required to diagnose CAPS. However, these patients are often too unwell to obtain results and wait for them. As such, investigations should not delay CAPS therapy, especially if there is strong clinical suspicion. Management of CAPS requires “triple therapy” with glucocorticoids, intravenous heparin, therapeutic plasma exchange, and/or intravenous immunoglobulin. Treatment for refractory disease is based on poor-quality evidence but includes anti-CD20 (rituximab) or anticomplement (eculizumab) monoclonal antibodies and other immunosuppressant agents, either alone or in combination. The rarity of this syndrome and the subsequent lack of randomized clinical trials have led to a paucity of high-quality evidence to guide management. Continued international collaboration to expand ongoing CAPS registries will allow a better understanding of the response to newer targeted therapy.

Learning Objectives

Identify patterns in clinical presentation for catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome

Explain the approach to investigating, classifying, and managing catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome

CLINICAL CASE

A 35-year-old woman presented with sudden confusion, dyspnea, progressive weakness, and purpura on her lower extremities. She had systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Initial findings included hypoxia, hypertension, resting tachycardia, and fever. Laboratory testing revealed an elevated D-dimer, thrombocytopenia, positive lupus anticoagulant (LAC), a moderate titer immunoglobulin G (IgG) anticardiolipin (aCL) antibody, and a negative anti–beta-2 glycoprotein I (aβ2GPI) antibody. Imaging studies showed bilateral pleural effusions and patchy splenic and renal infarcts, supporting a probable catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS). Upon consideration of the diagnosis, aggressive management included pulse- and maintenance-dose corticosteroids, daily therapeutic plasma exchange (TPE), and intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH). Given the refractory nature of her condition, she additionally received rituximab, intravenous IG (IVIG), and numerous immunosuppressive agents, including azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil. Her disease course was complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and multiorgan failure, necessitating intensive care admission and multidisciplinary involvement, including critical care, rheumatology, hematology, and nephrology.

Introduction

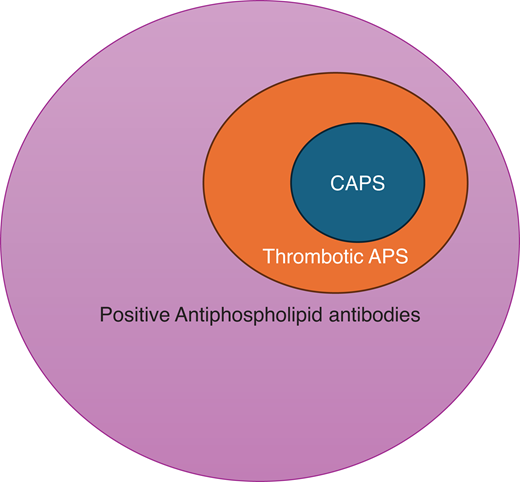

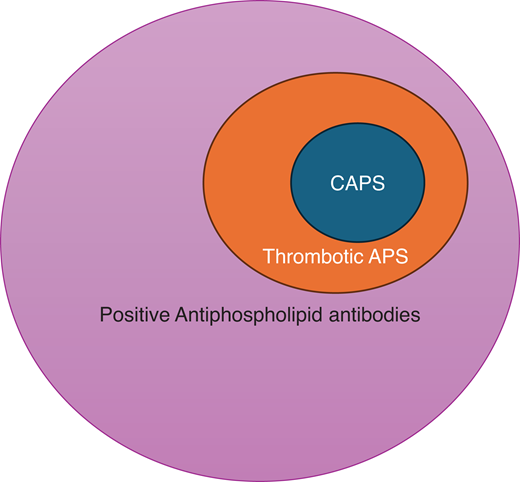

CAPS is an acute and severe form of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) marked by the rapid onset of multiple organ dysfunction, usually driven by microvascular ischemia (Figure 1). Although patients may present with simultaneous large- and small-vessel thrombosis, its sine qua non is microvascular thrombosis in multiple organs.

The overlap of CAPS and thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome. The presence of aPLs and complement gene abnormality fosters a procoagulant and proinflammatory environment, which increases the risk for macrovascular (venous and arterial) thrombotic events in APS. Approximately 1% of patients with APS develop a severe picture of catastrophic APS (CAPS). The “2-hit” theory suggests that the presence of additional precipitating factors (including infection, inflammation, pregnancy, surgery, trauma, etc) leads to a domino effect that results in activation of the complement system, endothelium, and coagulation cascade, as well as immune cell activation, which are key contributors to the pathogenesis of CAPS.

The overlap of CAPS and thrombotic antiphospholipid syndrome. The presence of aPLs and complement gene abnormality fosters a procoagulant and proinflammatory environment, which increases the risk for macrovascular (venous and arterial) thrombotic events in APS. Approximately 1% of patients with APS develop a severe picture of catastrophic APS (CAPS). The “2-hit” theory suggests that the presence of additional precipitating factors (including infection, inflammation, pregnancy, surgery, trauma, etc) leads to a domino effect that results in activation of the complement system, endothelium, and coagulation cascade, as well as immune cell activation, which are key contributors to the pathogenesis of CAPS.

APS is an autoimmune disorder characterized by thrombosis and obstetric morbidity in the presence of persistent antiphospholipid antibodies (aPLs). The syndrome's clinical and scientific foundations were first identified in the 1950s.1 The 1980s marked the identification of aPL as a distinct pathological phenomenon, leading to the formal recognition of APS as a unique clinical entity. Establishing APS as a syndrome has highlighted the complex interplay between the immune system and coagulation, resulting in significant advancements in diagnosis and management.

CAPS was distinguished in the medical literature in the 1990s when clinicians documented cases of APS patients experiencing sudden, severe, and widespread thrombotic events. This variant accounts for fewer than 1% of all APS cases but is notable for its rapid progression and high mortality rate, ranging from 37% to 48%.2,3 This clinical behavior underscores the critical role of early detection and aggressive treatment.

Clinical manifestations

Accumulating evidence from the International CAPS Registry, which includes voluntarily reported cases and published case reports, has shown that CAPS commonly affects women in the first 4 decades of life; however, cases have been described across all ages.3 There is great heterogeneity in the clinical presentation of CAPS. The predominant feature is the occurrence of thrombotic events within the small vessels over a short period at multiple sites. This contrasts with APS, which predominantly affects large vessels, with thrombosis typically limited to a single site. The stereotypical manifestations of CAPS have been identified from a large international registry of patients known as the CAPS Registry.3 Diffuse thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is characteristic of CAPS and can occur in virtually every organ but most frequently affects the kidneys (73%),4 lungs (60%),4 brain (56%),3,5 and heart (50%).6 Less frequently reported involvement includes the skin (45%), liver (34%), and gastrointestinal tract (12%), as well as the bone marrow, spleen, and adrenal gland.3,7,8 Patients may also present with intracranial, pulmonary, or retroperitoneal bleeding, which is, confusingly, due to underlying cerebral vein thrombosis, pulmonary microvascular thrombosis, and adrenal vein thrombosis, respectively. In addition, thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, and DIC can occur but are nonspecific and seen with other hematologic and nonhematologic disorders (Tables 1 and 2).9

Although CAPS may occur without an identifiable precipitant, most cases are associated with risk factors, including infection, surgery, trauma, malignancy, estrogen use, pregnancy, vaccination, active SLE, and many others.8 Of note, approximately 50% of patients are diagnosed with CAPS as their first manifestation of APS, and 28% of patients are known to have a prior diagnosis of SLE.3,8 An important and underestimated risk factor for CAPS is the discontinuation of anticoagulation in a patient with APS.8 For example, we previously published a case of a 42-year-old man with APS who developed CAPS 3 weeks following the sudden discontinuation of long-term low-molecular-weight heparin.10 His case was severe, with evidence of multisite microvascular thrombosis in the skin (acral purpuric lesions), mesentery, kidneys, central nervous system, and heart, along with marked thrombocytopenia. Given its severity, we maintain a strong clinical suspicion for CAPS in patients with a compatible presentation, particularly those with prior APS or SLE and especially in the setting of new-onset thrombocytopenia.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of CAPS relies heavily on clinical presentation, imaging, histopathological evidence (where available), and laboratory testing, including aPL. The classification criteria for CAPS have been previously proposed by the international congress on aPL in 2003 (Table 3).11 CAPS should be considered in a patient presenting with involvement of 3 or more organs or systems, an acute onset within 1 week, and confirmation of small vessel ischemia either on histopathology or appropriate imaging.11 Best practices for diagnosing and managing CAPS were articulated in a clinical practice guideline published in 2018.12 The guideline recommended that patients with suspected CAPS have a tissue biopsy to confirm microvascular involvement. However, the low sensitivity of the biopsy, in combination with the complexity of obtaining the sample (bleeding risk related to anticoagulation and/or thrombocytopenia, identification of a site to biopsy, and potential impact on delaying empiric treatment) reduces its utility for “real-time” management.

In our practice we consider the histopathological examination unnecessary in the setting of typical radiological findings and if obtaining an appropriate sample would interrupt or delay definitive therapy.

For laboratory evaluation, the panel recommended using aPL to confirm the diagnosis of CAPS without delaying empiric treatment, which is frequently required before laboratory test results have returned.12 The panel further suggested that testing be carried out as per accepted guidelines, with consideration for the appropriate timing of sample collection (ie, before initiating anticoagulation or TPE).13-15 aPL testing involves the assessment of aCL, aβ2GPI, and LAC. As per the 2020 International Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis guidelines, the LAC assay should involve a 3-step procedure with 2 test systems, including diluted Russell's viper venom time and silica clotting time.13 aCL and aβ2GPI are measured by solid-phase assays via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or automated systems techniques.14 Caution should be exercised when interpreting the positivity or negativity of aPL. Various clinical factors can influence aPL testing and result in a false positive, including infection, inflammation, TPE, and anticoagulant treatment (ie, warfarin and direct oral anticoagulants).13,16-18 In contrast, acute thrombotic events can result in falsely negative aPL.19,20 Unsurprisingly, how to interpret these tests and how much weight they should bear in such a high-stakes situation with an acutely unwell patient can be unclear. Although aPL positivity is required to establish the diagnosis of CAPS,12 based on our practice we suggest that in rapidly deteriorating patients, a presumptive clinical diagnosis can be made, and empiric treatment may be initiated before receipt and interpretation of aPL results.

The development of the 2023 American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) criteria has resulted in a fundamental change in how physicians classify APS.15 Notable laboratory changes include the following: 1) defining a clinically significant aCL or aβ2GPI as a titer greater than or equal to 40 based on the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and 2) asserting that an isolated IgM APL no longer confers sufficient points within the laboratory domain for classification. Several important clinical criteria changes have also occurred, including the deprioritization of venous thrombosis embolism with a high-risk venous thrombosis embolism profile and arterial thrombosis with high-risk cardiovascular disease. These aforementioned changes may lead to the incorrect use of these criteria and result in patients being reclassified as “non-APS” with the discontinuation of anticoagulation, which may inadvertently trigger CAPS. In contrast, the criterion has expanded to the clinical domain for microvascular thrombosis. We suspect that including microvascular events in the 2023 ACR/EULAR classification criteria will likely have significant, yet unrealized, future implications for approaching APS. On the one hand, these classification criteria may help facilitate APS identification, especially in critical situations. However, the inclusion of microvascular events as a clinical domain may increase the diagnosis of APS and thus increase the clinical consideration of CAPS when compatible manifestations occur. Conversely, misusing 2023 ACR/EULAR criteria as a diagnostic tool instead of classification criteria may increase the incorrect labeling of APS cases. The criteria were designed to prioritize specificity for homogenous research cohorts of true APS patients rather than be literally employed as strict clinical diagnostic criteria. We want to emphasize that the 2023 ACR/EULAR criteria should be used to explicitly classify APS and not interchangeably to diagnose CAPS. To prevent spuriously ruling CAPS in or out, it is important to use the diagnostic criteria specific to CAPS and to asses APS separately.

Management

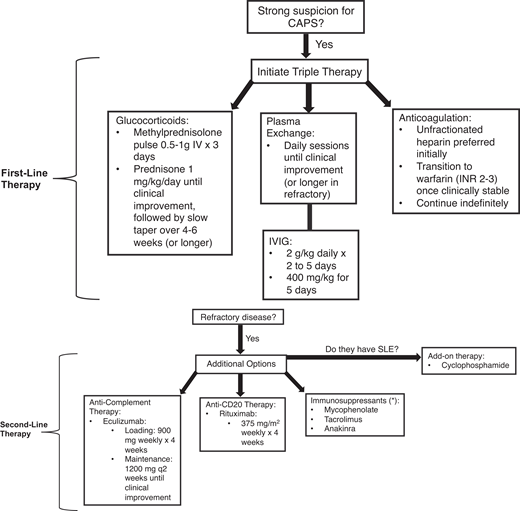

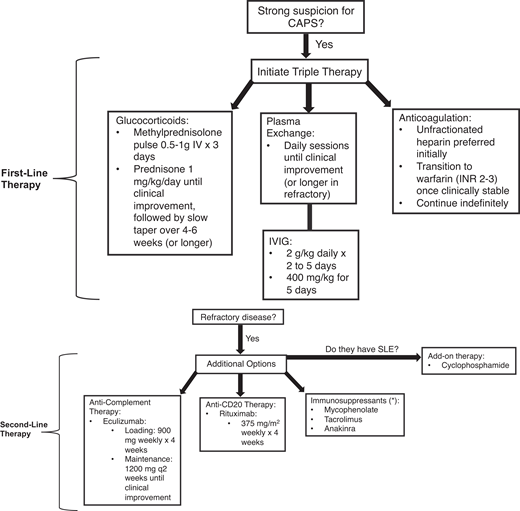

Management requires a multifaceted approach to mitigate life-threatening thrombotic events by addressing the hypercoagulable state, reducing inflammation, and removing circulating autoantibodies and coagulation components. The McMaster RARE-Bestpractices clinical practice guideline emphasizes the use of “triple therapy” first-line treatment, which includes high-dose glucocorticoids, anticoagulation, and TPE and/or IVIG (Figure 2).12

Recommended approach to managing CAPS. The following figure outlines our recommended approach to managing patients with CAPS. If there is a strong suspicion of CAPS, including characteristic clinical features and acute onset (within 1 week), then initiation of triple therapy may be warranted prior to confirmation of CAPS with histopathological or laboratory findings (ie, antiphospholipid antibodies). Triple therapy involves management with glucocorticoids, plasma exchange, and/or IVIG, as well as anticoagulation (preferably heparin). If there is a lack of clinical response (ie, progressive multiorgan failure, additional thrombotic events, or lack of improvement in complete blood count and hemolytic markers), then consider additive therapy with second-line options, including anti-CD20 (rituximab) or anticomplement (eculizumab) therapy or other immunosuppressive agents (either alone or in combination). If the patient has systemic lupus erythematous (SLE), in addition to the standard of care with hydroxychloroquine the use adjunct therapy with cyclophosphamide could be considered. If the patient remains refractory despite second-line therapy, then experimental agents or clinical trials would be warranted.

Recommended approach to managing CAPS. The following figure outlines our recommended approach to managing patients with CAPS. If there is a strong suspicion of CAPS, including characteristic clinical features and acute onset (within 1 week), then initiation of triple therapy may be warranted prior to confirmation of CAPS with histopathological or laboratory findings (ie, antiphospholipid antibodies). Triple therapy involves management with glucocorticoids, plasma exchange, and/or IVIG, as well as anticoagulation (preferably heparin). If there is a lack of clinical response (ie, progressive multiorgan failure, additional thrombotic events, or lack of improvement in complete blood count and hemolytic markers), then consider additive therapy with second-line options, including anti-CD20 (rituximab) or anticomplement (eculizumab) therapy or other immunosuppressive agents (either alone or in combination). If the patient has systemic lupus erythematous (SLE), in addition to the standard of care with hydroxychloroquine the use adjunct therapy with cyclophosphamide could be considered. If the patient remains refractory despite second-line therapy, then experimental agents or clinical trials would be warranted.

We administer a glucocorticoid pulse involving methylprednisolone at 0.5 to 1 g/d intravenously for 3 days, followed by maintenance with oral prednisone at 1 mg/kg/d (or equivalent) until clinical improvement, after which it can be slowly tapered over 4 to 6 weeks. Concerning anticoagulation, the agent of choice is intravenous UFH at therapeutic dosing, followed by a transition to warfarin (INR 2-3) indefinitely once clinically stable. In patients with prolonged activated prothrombin time (aPTT) at baseline due to the presence of the LAC antibody, we recommend monitoring anti-Xa levels as opposed to aPTT for therapeutic monitoring of UFH. To date, no randomized trials have compared TPE to IVIG. TPE and IVIG are generally not given at the same time. However, IVIG can be given following TPE, and the decision to use one over the other should be based on individual factors.10 In those with TMA, TPE is recommended over IVIG, whereas IVIG may be considered in patients with major bleeding with severe thrombocytopenia and poor access.12 TPE is typically performed once daily for 5 days but can be given longer in patients with refractory disease. TPE will typically involve a 1 to 1.5 plasma volume exchange per session. There is no consensus on the ideal replacement solution during TPE; solvent-detergent plasma and a 5% albumin solution have been proposed.21 At our center we typically use solvent-detergent plasma as the replacement fluid, based on the hypothesis that the removal of inhibitors of coagulation can predispose CAPS patients to further thrombosis and vice versa, that the removal of coagulation factors may add to the potential bleeding risk in thrombocytopenia. Concerning IVIG, despite the lack of high-quality evidence the general dosing is 2 g/kg/d for 2 to 5 days or 400 mg/kg for 5 days.12 Monitoring for treatment response typically involves daily blood work with a complete blood count and hemolytic markers and basic metabolic parameters reflective of end-organ function.

The role of adjunctive treatments such as antiplatelet agents is unclear; although they are widely used, good-quality evidence is lacking to guide this. When used in combination with systemic anticoagulation, they pose a significant risk of bleeding.16 Their use requires individualized risk assessment and monitoring. We suggest that antiplatelet therapy could be considered in patients in whom anticoagulation is contraindicated.

Refractory CAPS is exceedingly challenging to manage and is defined as the lack of improvement or worsening in clinical status despite triple therapy. Rituximab has been used in patients with either refractory disease or concurrent autoimmune conditions like SLE. Its inclusion in treatment protocols reflects a growing interest in targeting the underlying autoimmune mechanisms of APS. However, the evidence to guide its use is very anecdotal.12,22-25 High-quality evidence is unlikely to become available given the rarity of this condition and the acuity of the patients suffering from it. There is no current consensus on the ideal dosing regimen.12 We generally use a dose of 375 mg/m2 once weekly for 4 weeks. Alternatively, 500 to 1000 mg can be given twice, separated by 7 or 14 days.23 Given the observed abnormalities in complement regulatory pathways within APS pathogenesis, complement activation may be a fundamental precipitant in some patients.26 Anticomplement agents, including eculizumab, have been proposed for refractory CAPS. The evidence for eculizumab in CAPS is based on low-quality evidence with small case series and the CAPS Registry but could be considered in patients with a TMA phenotype with severe renal involvement.27-31 Although not formally assessed in clinical trials, the currently proposed regimen is loading with 900 mg/wk for 4 weeks, followed by maintenance with 1200 mg once every 2 weeks until clinical improvement. The ongoing evaluation of multiple complement-modulating therapies in a spectrum of seemingly unrelated diseases (eg, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome) provides an interesting perspective on this disorder's biology and potential management.

Other forms of single-agent or combination immunosuppression can be utilized for refractory disease or for those who do not respond quickly to TPE. In these circumstances we have reached for calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus), antinucleotide agents (azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil), or an anti–interleukin-1 monoclonal antibody (anakinra). Other biologics and immunosuppressive agents have been proposed in the literature for APS, including mTOR inhibitors (sirolimus),32 anti-CD20 (obinutuzumab),33 anti-CD38 (daratumumab),34 and anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF; adalimumab) monoclonal antibodies,35 but there is little supportive evidence for their use in CAPS. Defibrotide has been shown to modulate endothelial function, resulting in antithrombotic, anti-ischemic, and anti-inflammatory effects.36,37 It has demonstrated antineutrophil extracellular traps activity in APS.36,37 Patients with SLE and CAPS may benefit from cyclophosphamide,7,38 hydroxychloroquine,39 or the anti–B-cell-activating factor monoclonal antibody belimumab.40 Whether the therapies mentioned above provide meaningful clinical benefit is difficult to estimate given the critical illness experienced by these patients and the fact that, in most cases, multiple simultaneous interventions are implemented to save a patient's life. Teasing out which of these interventions have provided benefits usually proves impossible. Ongoing treatment is usually characterized by a sequential withdrawal of interventions, with those likely to be most toxic or most complex to administer withdrawn first as the patient's condition improves.

CAPS during pregnancy accounts for approximately 6% of all cases and represents a life-threatening situation with a high mortality rate for both mother (46%) and fetus (54%).41 Patients at risk for CAPS have been shown to have APS or the presence of aPL.41,42 The hypercoagulable state of pregnancy itself may pose a trigger for CAPS, but additional triggers have been hypothesized, including infection, flare in SLE, and anticoagulation withdrawal during delivery.41,42 Every effort should be made to reduce potential triggers for CAPS during pregnancy, including infection. Of note, hemolysis elevated liver enzymes and low platelet (HELLP) syndrome has been shown to precede CAPS, with a delay of days to weeks.42 Patients with a history of APS who develop HELLP syndrome should receive careful monitoring in the postpartum period for signs of CAPS. Further, anticoagulants should be resumed promptly in the postpartum period, even in those with thrombocytopenia, to reduce the risk of CAPS. For women with APS or a history of CAPS, the implications for subsequent pregnancies are significant. Pregnancy in APS patients is considered high risk due to the increased potential for maternal thrombosis and adverse obstetric outcomes, including recurrent miscarriage, preterm birth, preeclampsia, and fetal growth restriction. Careful prepregnancy planning and multidisciplinary management during pregnancy are crucial. Treatment typically involves low-dose aspirin and ongoing anticoagulation, usually with low-molecular-weight heparin. Frequent monitoring throughout pregnancy, with attention to both thrombotic and obstetric risks, is essential for optimizing maternal and fetal health, and such monitoring involves obstetrical ultrasounds to monitor placental blood flow and fetal health. In patients in which there is a high suspicion of active CAPS, treatment with triple therapy should be initiated. In addition, careful attention should be given to the well-being of the fetus, and delivery should be preplanned and strongly considered if the mother has refractory disease.

Prognosis

The outcomes for CAPS are poor, with an overall mortality of 36%. Triple therapy provides the best chance of survival and has been shown to significantly reduce mortality compared to no treatment (ie, 28.6% vs 75% mortality, respectively).43 In patients who do survive a first episode of CAPS, recurrence is relatively rare, but when it occurs, it presents similarly to the initial episode, with widespread thrombosis and the potential for severe multiorgan dysfunction and death. The risk of recurrence underscores the importance of continued anticoagulation therapy tailored to the patient's risk profile. Patients with recurrent disease frequently present earlier than their initial presentation, so therapy can be implemented more rapidly. Enabling patients to access advanced care, rather than seeking care through their usual care pathway, will mitigate avoidable complications.

The long-term implications of APS and CAPS necessitate a comprehensive, patient-centered approach to care that addresses the disease's physical and psychological impacts. For patients with a history of CAPS, this includes individualized risk assessment for recurrent disease and thrombosis, the management of long-term complications, and specialized care during subsequent pregnancies to minimize risks to both the mother and fetus. Continuous research and advances in understanding APS and CAPS are key to improving outcomes for these patients.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

Ultimately, after a rocky 6-week stay in the intensive care unit, including a below-knee amputation, the patient recovered. She eventually came off dialysis but continued to suffer from chronic renal insufficiency, persistent and variable thrombocytopenia, and flares of her SLE. Repeat APS testing revealed high-titer IgG aCL, whereas LAC testing was not repeated to avoid interruption in anticoagulant therapy. During a subsequent pregnancy, she developed severe hypertension and microangiopathic anemia with worsening renal function. An elective cesarean birth at 29 weeks' gestation was required. She eventually recovered with the use of TPE and pulse corticosteroids. Tubal ligation was performed at the time of the cesarean delivery, and long-term anticoagulation was maintained.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Brittany M. Salter: no competing financial interests to declare.

Mark Andrew Crowther: research funding/advisory board/ honoraria: Bayer, Astra Zeneca, Pfizer, Hemostasis Reference Laboratories, Eversana.

Off-label drug use

Brittany M. Salter: There are no drugs that are on label for these conditions; all the drugs are off label for this indication.

Mark Andrew Crowther: There are no drugs that are on label for these conditions; all the drugs are off label for this indication.