Key Points

The most common acquired BTK mutations detected at PD during pirtobrutinib treatment were T474X and L528W.

One-third of patients did not acquire any mutations at time of PD, illustrating the complexities of acquired resistance with pirtobrutinib.

Visual Abstract

Pirtobrutinib, a noncovalent, reversible Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi), demonstrated efficacy in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), resistant to covalent BTKi (cBTKi). We analyzed genomic correlations with response and resistance to pirtobrutinib in relapsed/refractory (R/R) patients with CLL pretreated with cBTKi enrolled in the phase 1/2 BRUIN trial. DNA sequencing was performed on peripheral blood mononuclear cells at baseline, on treatment, and at progressive disease (PD). Common alterations at baseline included mutations in BTK (43%), TP53 (38%), SF3B1 (25%), NOTCH1 (23%), ATM (19%), XPO1 (11%), PLCG2 (9%), BCL2 (8%), and 17p deletion (28%). Common baseline BTK mutations included C481S (85%), C481R (10%), C481F (6%), and C481Y (4%). At PD, 60 of 88 patients (68%) acquired ≥1 mutation, including 44% with acquired BTK mutations and 24% with other acquired mutations. A total of 55 acquired BTK mutations were detected in 39 patients, including gatekeeper mutations (T474I/F/S/Y/L, 26%), kinase-impaired L528W (16%), C481S/R/Y (5%), V416L (2%), and A428D (1%) and others proximal to the adenosine triphosphate–binding pocket, D539A/G/H (1%) and Y545N (1%). Decrease or complete clearance of BTK C481x was observed at PD in 36 of 43 patients (84%). Using a more sensitive assay, 37% (18/49) of acquired BTK mutations were detected at baseline at low allele frequency. Using a highly sensitive assay at progression, a similar frequency of acquired BTK mutations (39%) was detected, and all patients had detectable acquired mutations. This study highlights the complex clonal dynamics of BTK mutations in patients with R/R CLL undergoing pirtobrutinib treatment, and the extent of resistance without an obvious genomic driver. Trial registration: #NCT03740529 at www.ClinicalTrials.gov.

Introduction

Management of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and other B-cell malignancies has been transformed in recent years by use of Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi), small-molecule compounds that bind and block the catalytic activity of BTK.1 BTK plays a pivotal role in B-cell maturation by regulating cellular development and differentiation as part of the B-cell receptor (BCR) signaling pathway.2,3 Aberrant signaling through the BCR, including BTK, is central to the phenotype and biology of the malignant clone of CLL and other B-cell malignancies.4

Ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib are covalent BTKis (cBTKi) approved for the treatment of CLL.5-7 These BTKis covalently bind to the cysteine 481 (C481) residue in the BTK active site, inhibiting autophosphorylation and suppressing downstream signaling.8,9 Despite the efficacy of these treatments, progressive disease (PD) can occur because of various resistance mechanisms, most commonly including mutations in BTK or the downstream BTK target phospholipase C gamma 2 (PLCG2).10 Resistance to cBTKi in CLL is predominantly mediated by BTK C481 substitutions that disrupt binding of cBTKi.11,12 BTK L528W mutation has also been reported in the context of zanubrutinib resistance, whereas BTK T474 substitutions have been reported in the context of acalabrutinib resistance.13,14

Unlike cBTKi, non-cBTKi do not require binding to the C481 residue of BTK and inhibit both wild-type and C481-mutant BTK.15,16 Pirtobrutinib is a noncovalent, reversible, and highly selective BTKi that has demonstrated activity in cBTKi pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) CLL.17 In December 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration granted accelerated approval for the treatment of R/R CLL previously treated with at least 2 lines of systemic therapy, such as both BTKi and BCL-2 inhibitor (BCL2i) exposure.18,19

Here, we performed targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) analyses on peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) collected at baseline from a subset of cBTKi pretreated patients with R/R CLL, and at progression in those who had paired samples available at the 2 time points, as part of the multicenter, international, phase 1/2 BRUIN trial (www.ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03740529).

Methods

Study cohort

This study included patients with R/R CLL who were confirmed eligible and treated with pirtobrutinib in the phase 1/2 BRUIN trial.17 The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards or independent ethics committees overseeing each site and was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and local laws. All patients provided written informed consent for clinical research and NGS. Patients enrolled between March 2019 and 5 May 2023 data freeze were included. Pirtobrutinib dose was selected as specified by the protocol in the clinical trial article evaluating the safety and efficacy of this drug. Patients with documented PD were allowed to remain on pirtobrutinib if, in the opinion of the investigator, the patient was tolerating and deriving clinical benefit from continuing the study treatment.20

Samples and genomic analyses

Blood was collected serially for genomic analyses. Genomic DNA was extracted from PBMCs collected at baseline and at progression. Targeted NGS was centrally assessed using 2 different panels containing 218 genes (Cancer Genome Inc, Rutherford, NJ) and 322 genes (NeoGenomics Laboratories, Fort Myers, FL; see supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website, for the list of genes), with a limit of detection (LoD) of 5% variant allele frequency (VAF). For serial paired samples that were sequenced with different panels, analysis was restricted to 74 genes in common between the panels. Fluorescence in situ hybridization and immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IGHV) mutation status were centrally assessed on baseline PBMCs. A more sensitive NGS assay (TruSight Oncology 500 circulating tumor DNA) with a LoD of 0.5% VAF was used to detect the presence of subclonal mutations and is noted when presented. Further details are described in the supplemental Material.

Clinical outcomes

Response was assessed according to criteria from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia, 2018.21 Data analysis cutoff date was 5 May 2023.

Statistical analysis

Overall response rate (ORR) was calculated as the proportion of patients with best overall response (BOR) of partial response with lymphocytosis or better, and was presented with 2-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) based on the exact binomial distribution. Median time on treatment was calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Median follow-up time was calculated using the reverse Kaplan-Meier method. The association between baseline features and progression-free survival (PFS) was assessed using univariable Cox proportional hazards regression models. Comparisons between groups were performed using Fisher exact test for categorical variables. When applicable, multiple testing correction was performed using the false discovery rate (q) method and q < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R software version 4.1.3 (available at www.r-project.org) and Bioconductor version 3.13.

Results

Baseline genomic profile of cBTKi pretreated patients with CLL

A total of 245 cBTKi pretreated patients with R/R CLL who received pirtobrutinib monotherapy in the BRUIN trial and had baseline sequencing data were included in this analysis (supplemental Figure 1). Patient baseline characteristics are described in supplemental Table 2. Patients previously received ≥1 of the following cBTKi: ibrutinib (n = 218 [89%]), acalabrutinib (n = 40 [16%]), and zanubrutinib (n = 7 [3%]). The median number of previous lines of therapy was 4 (range, 1-11). The median time on pirtobrutinib was 19 months (range, 0.2-49). The safety and efficacy of pirtobrutinib in CLL were previously reported.17 At the time of data cutoff, the ORR to pirtobrutinib in these 245 patients was 82%, the median time on pirtobrutinib was 20.7 months (95% CI, 18.4-24.0), and the treatment was ongoing for 33% of patients (supplemental Table 2; Figure 1A).

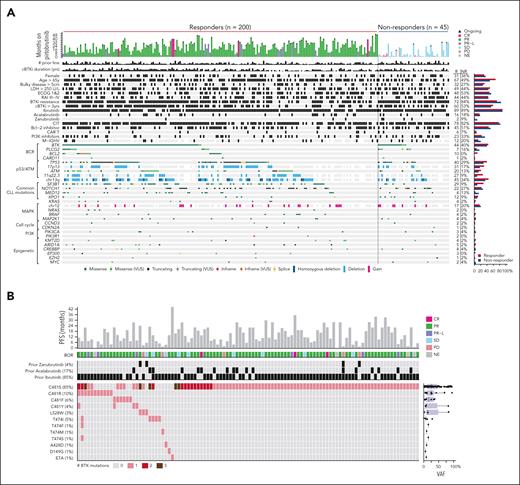

Baseline genomic profile of cBTKi pretreated CLL patients. (A) Oncoprint of genomic alterations at baseline in patients with CLL who responded and those who did not respond to pirtobrutinib. (B) Oncoprint of BTK alterations detected at baseline, pirtobrutinib response, and outcome in patients harboring BTK mutations. CR, complete response; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NE, not evaluable; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PR, partial response; PR-L, partial response with lymphocytosis; SD, stable disease; VUS, variant of unknown significance.

Baseline genomic profile of cBTKi pretreated CLL patients. (A) Oncoprint of genomic alterations at baseline in patients with CLL who responded and those who did not respond to pirtobrutinib. (B) Oncoprint of BTK alterations detected at baseline, pirtobrutinib response, and outcome in patients harboring BTK mutations. CR, complete response; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NE, not evaluable; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PR, partial response; PR-L, partial response with lymphocytosis; SD, stable disease; VUS, variant of unknown significance.

Targeted NGS was performed on PBMCs collected at baseline to investigate the genomic profile of heavily pretreated patients with R/R CLL. Common mutations at baseline were: BTK (43%), TP53 (38%), SF3B1 (25%), NOTCH1 (23%), ATM (19%), XPO1 (11%), PLCG2 (9%), and BCL2 (8%). Fluorescence in situ hybridization abnormalities included del(13q) (43%), del(17p) (28%), del(11q) (23%), and trisomy 12 (17%; Figure 1A). All 19 patients with BCL2 mutation were previously treated with a BCL2i, suggesting prior emergence of resistant clones to venetoclax.22 We detected a total of 24 PLCG2 mutations among 21 patients (R665W [5], L845F [5], S707F [3], D993G [2], D1144G [2], R665Q, D334H, V886A, E1138K, M1141R, D1140G, and D1140E). We observed co-occurrence of TP53 mutations and del(17p) in 50 of 185 patients (27%) and co-occurrence of ATM mutations and del(11q) in 25 of 185 patients (14%), suggesting biallelic inactivation in these tumor suppressor genes.

A total of 148 BTK mutations were detected at baseline in 106 patients (43%), with a LoD of 5% VAF. Two or more BTK mutations in the same baseline sample were observed in 27 patients (11%; Figure 1B). The most common BTK mutations detected at baseline were C481S (85%), C481R (10%), C481F (6%), and C481Y (4%), with the C481S substitution having the highest VAF (median, 25%). Non-C481 BTK mutations primarily included L528W (3%) and T474I (5%). Other BTK mutations (T474F/M/S, A428D, D149G, and E7A) were uncommon. Notably, L528W was detected in 2 of 7 patients previously exposed to zanubrutinib, and T474I was detected in 2 of 40 patients previously exposed to acalabrutinib (Figure 1B; supplemental Figure 2A). Among 3 patients with detectable BTK L528W at baseline, their BOR was partial response, stable disease, and PD. Among 6 patients with detectable BTK T474× at baseline, their BOR was PR (4), SD (1), and PD (1; Figure 1B).

We also investigated the association between the duration of prior cBTKi therapy and the BTK mutational landscape. A longer duration of prior cBTKi therapy was detected among patients with BTK mutations at baseline, compared to those without BTK mutations at baseline (median, 4.1 vs 2.6 years; P < .0001). However, no difference in the duration of prior cBTKi therapy was observed between patients with single BTK mutation compared to those with multiple BTK mutations at baseline (median, 4.0 vs 4.2 years; P = .97). A positive correlation was observed between the duration of prior cBTKi therapy and mean BTK VAF at baseline (Spearman ρ = 0.25; P = .009; supplemental Figure 2B).

We further investigated how the baseline clinical and genomic features of patients differed according to the reason for discontinuation of prior cBTKi treatment (supplemental Figure 2C; supplemental Table 3). A statistically significantly higher frequency of BTK mutations (52% vs 17%; P < .01; q < 0.01) and higher frequency of unmutated IGHV genes (26% vs 9%; P < .01; q < 0.01) were found in patients who discontinued prior cBTKi because of PD compared with those who discontinued due to toxicity/other reasons.

Genomic determinants of response to pirtobrutinib

No statistically significant differences were observed in the frequency of most baseline clinical and genomic features between responders (n = 200) and nonresponders (n = 45) to pirtobrutinib (Figure 1; supplemental Table 3). Discontinuation of prior cBTKi due to PD was reported among 72% of responders and 84% of nonresponders (P = .09; q = 0.51; supplemental Table 3). The frequency of BTK and TP53 mutations was similar between responders and nonresponders (44% vs 40% [P = .74; q = 0.93] and 40% vs 29% [P = .23; q = 0.75]). The frequency of mutated IGHV was similar between responders and nonresponders (12.2% vs 20%; P = .21; q = 0.75). The frequency of SF3B1 mutations (29% vs 9%; P = .004; q = 0.19) and del(11q22) (27% vs 9%; P = .02; q = 0.22) were higher in responders. BCL2 mutations were only detected among responders (10% vs 0%; P = .03; q = 0.22). The frequency of MED12 and PLCG2 mutations was higher in nonresponders (4% vs 13% [P = .017; q = 0.22] and 7% vs 16% [P = .07; q = 0.50]; supplemental Table 3; supplemental Figure 2D). Evaluation of the prognostic value of baseline clinical and genomic features on PFS showed that prior cBTKi resistance; elevated lactate dehydrogenase; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status; prior exposure to BCL2i, phosphoinositide 3-kinase inhibitor, or chemoimmunotherapy; and PLCG2 or EZH2 mutations (q < 0.05) were associated with increased risk of progression in an exploratory analysis (supplemental Table 3).

Mechanisms of resistance to pirtobrutinib

At a median follow-up of 29 months (95% CI, 28.8-31.6), 139 patients (57%) from the overall population experienced PD on pirtobrutinib. A subset of 88 patients had available paired PBMC samples collected at baseline and at PD for sequencing (supplemental Figure 1; Figure 2). Baseline clinical characteristics of these 88 patients were comparable to the overall population with a similar ORR (83% vs 82%, respectively; supplemental Table 2). The median duration of pirtobrutinib treatment was 16.4 months (95% CI, 13.1-18.6), 6 patients were still on treatment at the time of data cutoff, and the median PFS was 10.3 months (95% CI, 9.2-13.6; supplemental Table 2; Figure 2A).

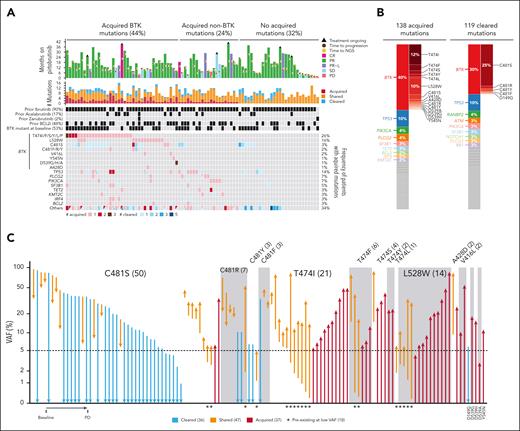

Clonal evolution under pirtobrutinib treatment. (A) Oncoprint of cleared and acquired mutations (C481S, P = 5.8 × 10-6; T474I, P = 6.4 × 10-5; L528W, P = .001, P value derived from the paired t test) (B) Bar plots showing the distribution of acquired mutations and cleared mutations by genes and by BTK residues, each color represents a gene. (C) VAF at baseline and at progression (PD) for 120 BTK mutations detected at baseline and/or PD. For Figure 3C, the high-sensitivity assay (LoD, 0.5% VAF) was used at baseline.

Clonal evolution under pirtobrutinib treatment. (A) Oncoprint of cleared and acquired mutations (C481S, P = 5.8 × 10-6; T474I, P = 6.4 × 10-5; L528W, P = .001, P value derived from the paired t test) (B) Bar plots showing the distribution of acquired mutations and cleared mutations by genes and by BTK residues, each color represents a gene. (C) VAF at baseline and at progression (PD) for 120 BTK mutations detected at baseline and/or PD. For Figure 3C, the high-sensitivity assay (LoD, 0.5% VAF) was used at baseline.

Our analysis demonstrated that 119 mutations in 54 patients (61%) initially found at baseline were not detected at time of PD (ie, cleared), with a LoD of 5% (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Table 4). Pirtobrutinib treatment led to the clearance of 36 BTK mutations among 24 patients. No significant difference in ORR was observed in patients without or with BTK mutation clearance (52/64 [81%] vs 21/24 [88%]; P = .75). Most of these mutations were C481x substitutions, including C481S (30), C481Y (2), C481R (2), C481F (1), and D149G (1) (Figure 2C; supplemental Table 4). In total, 36 of 43 patients (84%) with BTK C481x mutations at baseline showed a decrease or clearance of C481x clones at PD (P = 5.8 × 10-6).

We compared mutations detected in samples collected at baseline and at PD. A total of 138 acquired mutations were detected in 60 of 88 patients (68%): 44% acquired a BTK mutation and 24% acquired a mutation in a different gene, whereas 32% of patients with PD did not acquire mutations in this targeted sequencing panel (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Table 4). The duration of treatment was similar between patients with and without acquired mutations (median, 16.5 vs 16.1 months; P = .91; Figure 2A). A total of 35 of 60 patients (58%) had multiple acquired mutations, with up to 8 mutations identified in a single patient (Figure 2A). The most frequently acquired mutations were in BTK (n = 55 in 39 patients), TP53 (n = 14 in 12 patients), PLCG2 (n = 6 in 6 patients), and PIK3CA (n = 6 in 6 patients; Figure 2A-B; supplemental Table 4). BCL2 mutations were detected at baseline in 19 of 131 patients, all of whom had been previously treated with a BCL2i. We determined that all 3 patients who acquired BCL2 mutations had prior exposure to a BCL2i. The most prevalent residues among acquired BTK mutations were T474x gatekeeper mutations T474I/F/S/Y/L (n = 28 in 23 patients), kinase-impaired L528W (n = 14 in 14 patients), and C481S/R/Y (n = 6 in 4 patients), as well as others proximal to the adenosine triphosphate–binding pocket (n = 7 in 5 patients), including D539A/G/H (n = 3 in 1 patient), V416L (n = 2 in 2 patients), Y545N (n = 1), and A428D (n = 1; Figure 2C). The median VAF of acquired T474x and L528W at PD were 16% (range, 6%-85%) and 20% (range, 4%-87%), respectively (supplemental Table 4). Of interest, while recognizing small numbers of patients, the frequency of patients with acquired BTK mutations was relatively similar across the type of prior cBTKi: ibrutinib (35/79 [44%]), acalabrutinib (8/15 [53%]), and zanubrutinib (1/2 [50%]). These changes overall reflect shifts in the clonal architecture that result from therapeutic pressure of pirtobrutinib on the CLL clones.

Samples from 79 of 88 patients with sufficient material at baseline were resequenced using a more sensitive sequencing assay (10× lower LoD, 0.5% VAF). We assessed whether acquired BTK, PLCG2, and BCL2 mutations preexisted at lower VAFs at baseline. All available patients with acquired PLCG2 (n = 5) and BCL2 (n = 3) mutations had subclonal mutations detected at baseline (supplemental Table 4). Among 39 patients with acquired BTK mutations, 36 had available samples at baseline for resequencing. We determined that 18 of 49 BTK mutations (37%) (T474I [7], L528W [4], T474F [2], T474L, C481S [2], C481Y, and C481R) among 15 patients were preexisting at baseline (VAF range, 0.2%-5.6%; Figure 2C; supplemental Table 4). Of note, among 10 patients who were exposed to ibrutinib only, 13 subclonal BTK mutations were detected with the more sensitive assay, including T474I (4), T474F (2), T474L, and L528W (3). Among 23 T474x acquired mutations, 10 (43%) were detected at baseline at low VAF (range, 0.2%-5.6%), and among 13 L528W acquired mutations, 4 (30%) were detected at baseline at low VAF (range, 0.2%-2.8%). The ORR among patients with preexisting, low VAF T474x (13/14 [93%]) and L528W (3/4 [75%]) mutations was comparable to the PD group. The median PFS among patients with baseline BTK (using standard and high sensitivity) T474x was 9.2 months (95% CI, 7.4-22.3) and L528W was 6.7 months (95% CI, 1.7-not available). Among BTK mutations detected at both time points, we observed that 10 of 16 C481S mutations and 4 of 5 C481R mutations had a lower VAF at PD. In contrast, T474x (n = 16), L528W (n = 4), C481F (n = 2), and A428D (n = 1) mutations identified at baseline had a higher VAF at PD (Figure 2C).

Samples from 31 patients with sufficient DNA available at progression were resequenced using a higher sensitivity sequencing assay. A total of 806 acquired mutations were detected in all 31 patients: 39% acquired a BTK mutation and 61% acquired a mutation in a different gene (supplemental Table 5). A total of 31 acquired BTK mutations were detected in 12 patients, of which 19 were subclonal (<5% VAF) in novel residues such as T316A, G389D, V416M, T474N (2), T474P, L528S, K433_E434insKK, and T474_M477delinsIEYI (supplemental Figure 3A). A total of 21 acquired PLCG2 mutations were detected in 8 patients and were all subclonal, as is common with PLCG2 mutations (VAF range, 0.08%-1.34%). Additionally, 8 acquired subclonal (<1%) KRAS mutations were identified in 5 patients, and 5 acquired BCL2 mutations were identified in 4 patients (supplemental Table 5).

Notably, most acquired BTK resistance-associated mutations were in the kinase domain within the adenosine triphosphate–binding pocket or activation loop (supplemental Figure 3). To characterize the catalytic activity of BTK mutants, a representative subset was evaluated in enzyme and cellular assays (supplemental Tables 6 and 7). In agreement with previous findings,12 both catalytically active and inactive variants were observed, including the novel Y545N (active) and D539G/H (inactive) variants (supplemental Table 6; supplemental Figure 4). Selected BTK variants were expressed in BTK knockout Ramos B cells and evaluated for rescue of calcium flux after immunoglobulin M stimulation. All single-mutation BTK variants increased calcium flux to similar levels as wild-type BTK, indicating that downstream signaling was maintained with both catalytically active and inactive variants (supplemental Figure 4C). Consistent with a role in promoting resistance, pirtobrutinib binding affinity was reduced (wild-type BTK dissociation constant = 0.4 nM; variants range dissociation constant = 2.1-36.4 nM), residence time decreased (wild-type BTK t1/2 = 5.6 hours; variants range t1/2 = 0.9 seconds to 0.5 hour), and variants with kinase activity were less sensitive to pirtobrutinib inhibition in cellular BTK phosphorylation assays (supplemental Tables 7 and 8; supplemental Figure 5).

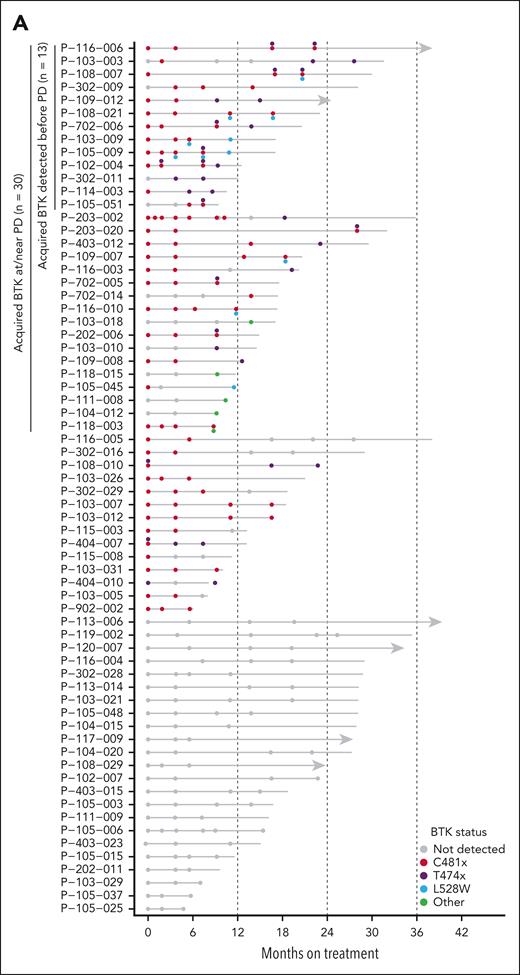

To further evaluate the longitudinal patterns of pirtobrutinib resistance, we sequenced additional time points before PD. In total, 67 of 88 patients who demonstrated PD had available samples collected before PD, ranging from 1 to 6 additional time points (Figure 3). Thirty of these 67 patients had acquired BTK mutations at PD. Among these 30 patients, 13 (43%) had acquired BTK mutations detected in time points collected prior to PD, up to 7.6 months preceding PD (Figure 3B). Notably, for patients with multiple emerging BTK mutations, it appears that these mutations are present in distinct subclones, as indicated by their different VAF, and by their presence on different alleles when this could be assessed (supplemental Figure 6). This has also been previously described in patients receiving pirtobrutinib treatment.23

Longitudinal patterns of pirtobrutinib resistance. (A) Timeline showing BTK mutations detected at multiple time points in 67 PD patients with available intermediate time points. (B) VAF at multiple time points in 13 patients with acquired BTK mutations detected in time points collected before PD.

Longitudinal patterns of pirtobrutinib resistance. (A) Timeline showing BTK mutations detected at multiple time points in 67 PD patients with available intermediate time points. (B) VAF at multiple time points in 13 patients with acquired BTK mutations detected in time points collected before PD.

Clonal evolution associated with LTR to pirtobrutinib

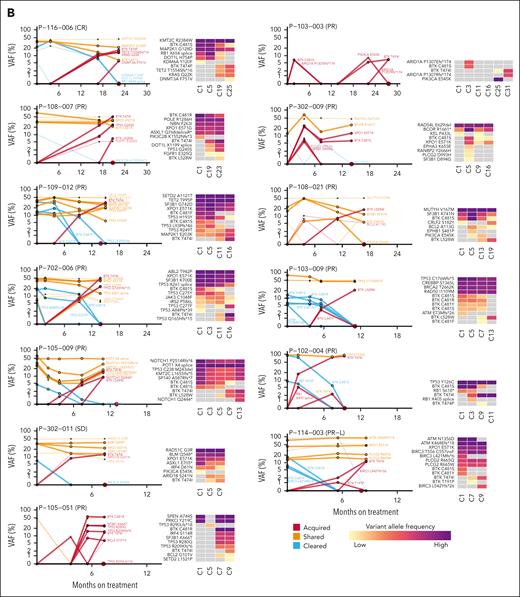

The clonal evolution of CLL in patients with long-term response (LTR) to pirtobrutinib was also assessed. A total of 54 responders were on pirtobrutinib for >24 months and were alive without documented PD on or before data cutoff. Of these, 16 LTR patients had available longitudinal sequencing data from samples collected at last visit (supplemental Figure 1). Samples collected at baseline and at last visit were compared, and 25 acquired mutations were identified in 14 of 16 LTR patients (88%; Figure 4; supplemental Table 9). Among these 14 patients with LTR, 8 (57%) had multiple acquired mutations, with up to 3 mutations. However, analysis of additional longitudinal samples obtained between baseline and last visit revealed that acquired BTK mutations did not emerge at the intermediate time points evaluated (cycle 5), in contrast to what was observed in 43% of patients with progression (Figure 4B). Our analysis also revealed that long-term pirtobrutinib treatment cleared a total of 35 mutations in 12 LTR patients, including 8 BTK mutations (6 C481S and 2 C481Y) among 6 patients. Clearance of mutations in LTR is likely because of clearance of circulating CLL cells.

Acquired resistance in long-term responders. (A) Acquired, shared, and cleared mutations in 16 LTR patients. (B) Timeline showing BTK mutations detected at multiple time points in 16 LTR patients.

Acquired resistance in long-term responders. (A) Acquired, shared, and cleared mutations in 16 LTR patients. (B) Timeline showing BTK mutations detected at multiple time points in 16 LTR patients.

Discussion

We report, to our knowledge, the largest study of mechanisms of response and resistance to pirtobrutinib. The most common mechanisms of acquired resistance are BTK T474x mutations in 26% and BTK L528W mutations in 16% of patients. Using a highly sensitive assay, we find that 37% of these mutations can be detected at baseline, likely having emerged on prior cBTKi therapy.

Among baseline characteristics, mutations in BTK, TP53, PLCG2, and BCL2 in patients with prior venetoclax exposure were prominent. In this study, 43% patients had BTK mutations and 9% had PLCG2 mutations at baseline, consistent with a recent analysis of 98 patients with CLL who progressed on ibrutinib,24 suggesting other mechanisms do drive a significant fraction of cBTKi resistance. Previously described mechanisms included mutations in the downstream NF-κB pathway or outside of the BCR pathway,25 increased BTK synthesis,26 or alternative-site BTK mutations.23

Pirtobrutinib efficacy was observed regardless of baseline clinical characteristics or mutations (such as BTK, TP53, SF3B1, and del(11q)), consistent with prior ibrutinib studies.27 The small number of BTK T474x and L528W mutations detected at baseline, even with the highly sensitive assay, does not allow direct comparison between nonresponders and responders, although ORR appeared similar regardless of these mutations. However, patients with L528W mutation appeared to have a short PFS, needing confirmation in larger studies. Additionally, BCL2 mutations, probably emerging on prior venetoclax, were observed in patients responding to pirtobrutinib. PLCG2 mutations were more frequent among nonresponders, consistent with prior studies.17 Several studies have reported that PLCG2 mutations increase the activity of the associated phospholipase enzyme and promote BCR signaling, despite BTK inhibition.11,28,29 It is important to note that while many associations between baseline features and PFS were observed, these associations are based on a subset analysis of a phase 1/2 study and will need to be confirmed in larger or randomized studies. Although ORR and PFS are correlated endpoints, PFS captures more nuanced information than ORR, and differences in association with baseline characteristics may therefore be observed.

Our analyses revealed that most patients acquired at least 1 mutation, with BTK mutations being the most frequently acquired. The BTK T474x gatekeeper mutations can reduce the affinity of pirtobrutinib but preserve BTK kinase activity.30 Mutations at BTK L528W result in kinase-impaired BTK12 and were observed among patients progressing on zanubrutinib and occasionally ibrutinib.13 Other acquired mutations including BTK C481R/Y, V416L, A428D, and D539G/A/N also impair BTK kinase activity. Notably, kinase-impaired mutations detected at baseline in BTK C481R/Y were cleared or decreased with pirtobrutinib treatment, suggesting that not all kinase-impaired BTK mutations confer resistance to pirtobrutinib. Several studies investigating the novel scaffolding functions of kinase-impaired BTK mutants suggest HCK and ILK as surrogate kinases to maintain BCR signaling.14,31 Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells with BTK kinase-impaired mutations continue to proliferate but remain sensitive to BTK degradation, suggesting a potential role of BTK degraders as next-line of treatment.32 In vitro studies have suggested activity of cBTKi against specific mutations, such as acalabrutinib against L528W, suggesting that therapeutic sequencing back to cBTKi may be possible depending on mutation and warrants clinical testing. We also evaluated sequencing data from long-term responders to pirtobrutinib. Clearance of BTK and TP53 mutations was observed for ∼2 years, highlighting sustained suppression of these clones by pirtobrutinib. Nonetheless, new mutations were observed in most cases, indicating ongoing clonal evolution during response.33

A limitation noted in other studies12 was the lack of sensitivity of the sequencing assay for detecting subclonal mutations. We addressed this by resequencing available baseline and PD samples with a 10 times more sensitive NGS method. The high-sensitivity assay revealed that 37% of acquired BTK mutations were present at a lower VAF at baseline. This underscores the presence of subclonal populations, likely emerging during prior cBTKi treatments. Importantly, ORR among patients with subclonal BTK T474x and BTK L528W mutations detected at baseline was 93% and 75%, respectively. However, sample sizes limit the interpretation of these results. The high-sensitivity assay revealed a similar frequency of patients with acquired BTK mutations, but also identified novel subclonal mutations in BTK, PLCG2, and BCL2 that standard clinical sequencing assays would have missed. All acquired PLCG2 mutations were subclonal (VAF < 2%), and 4 of 5 BCL2 acquired mutations were detected in patients with prior exposure to BCL2i. Other subclonal mutations, such as KRAS, were identified, although their clinical significance in the context of pirtobrutinib resistance remains unclear. Another limitation is that this study only accessed PBMCs, capturing only the genomic picture of circulating malignant cells. A few C481S clones rose at PD, perhaps related to another cooperating associated driver, such as TP53 mutations.23

Using the standard clinical sequencing assay, 32% of patients with progression on pirtobrutinib had no detectable acquired mutations. However, the high-sensitivity assay revealed that all carried acquired mutations, mostly subclonal, with unclear clinical significance. Therefore, additional transcriptomic and/or epigenetic mechanisms of resistance cannot be ruled out and warrant future investigation. The genomic landscape of resistance described is seen in heavily pretreated patients with prior cBTKi exposure. Future studies need to address resistance mechanisms with pirtobrutinib in treatment-naïve patients with CLL. Ongoing clinical trials evaluating pirtobrutinib in the first-line setting (BRUIN CLL-313 and BRUIN CLL-314) will provide valuable insights.

Our results demonstrate that treatment with pirtobrutinib in cBTKi pretreated patients leads to clearance of preexisting C481x mutations and the outgrowth of the gatekeeper T474x mutation or the kinase dead L528W mutation in about half of patients, raising questions about optimizing the sequence of covalent and non-cBTKi, the impact of venetoclax on clonal evolution, and the potential activity of new investigational BTK degraders.34,35

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the clinical trial participants and their caregivers, without whom this work would not have been possible. The authors also thank Mary S. Rosendahl and Kevin Ebata of Eli Lilly and Company for preclinical analyses; Abby Atwater and Lynn Naughton, employees and shareholders at Eli Lilly and Company, for providing medical writing and editorial support throughout the development of this article; and Hannah M. Messersmith, employee and shareholder at Eli Lilly and Company, for providing medical writing support and editorial support during early drafting.

This study was supported by funding from Eli Lilly and Company and supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Center support grant (P30CA008748). J.A.W. is a clinical scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. V.G. is supported by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center support grant (P30CA016672) from MD Anderson Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) Moon Shot Program; and has received an NCI-R21 grant, a CLL Global Research Fundation Alliance Grant, and a CLL-GRF postdoctoral fellowship. This study was supported by funding from Loxo Oncology, a wholly owned subsidiary of Eli Lilly and Company. W.G.W. was supported by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (Chair, CLL), NIH/NCI (award number P30CA016672), and used MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant shared resources.

The funder had a role in study design, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and approved the submission of the manuscript for publication. Employees of the sponsor contributed to the development of the study, samples and clinical data collection, laboratory analyses, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript.

Authorship

Contribution: B. Nguyen, H.W., and W.G.W. conceptualized the study; H.W., S.C.M., H.S.R., L.M.H., A.P., and V.G. designed the study; J.R.B., H.S.R., S.C.B., T.A.E., and W.G.W. acquired, analyzed, and interpreted study data; B. Nguyen, S.P.D., M.B., B.N., P.A., C.W., and V.G. analyzed and interpreted study data; S.C.M., K.P., C.S.T., N.N.S., and W.J. acquired and interpreted study data; L.M.H. and A.P. acquired and analyzed study data; C.Y.C. and L.E.R. acquired study data; S.I.T. interpreted study data; B. Nguyen, H.W., H.S.R., L.M.H., A.P., and S.C.B. drafted the manuscript; and all authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version, vouched for the completeness and accuracy of the data and adherence to the protocol, and agreed to the content of the manuscript and submission.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.R.B. reports grants or contracts paid to her institution from BeiGene, Gilead Sciences, iOnctura, Loxo/Lilly, MEI Pharma, Secura Bio, and TG Therapeutics; reports royalty payments from UpToDate; reports personal consulting fees received from AbbVie, Acerta Pharma/AstraZeneca, Alloplex Biotherapeutics, BeiGene, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Galapagos NV, Genentech/Roche, Grifols Worldwide Operations, Hutchmed, InnoCare Pharma Inc, iOnctura, Janssen, Kite Pharma, Eli Lilly and Company, MEI Pharma, Merck, Numab Therapeutics, Pfizer, and Pharmacyclics; and is a paid member on the data safety monitoring committee (ad-hoc) at Grifols Therapeutics. B. Nguyen and H.W. report stock or stock options from Eli Lilly and Company. S.C.M. reports support for this article from Eli Lilly and Company; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Eli Lilly and Company; stock or stock options at Eli Lilly and Company; and receipt of equipment, materials, drugs, medical writing, gifts, or other services from Eli Lilly and Company. N.M. reports support for the this article, support for attending meetings, and stock or stock options from Eli Lilly and Company. H.S.R. reports support for this study in the form of employee salary and employee stock or stock options from Eli Lilly and Company. L.M.H. reports support for this article from Eli Lilly and Company; and stock or stock options from Eli Lilly and Company. S.C.B. reports support for this article from Eli Lilly and Company; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Eli Lilly and Company for attendance at American Association for Cancer Research 2023; and stock or stock options at Eli Lilly and Company. J.A.W. reports grants or contracts from the National Cancer Institute, Leukemia and Lymphoma Society, and CLL Global Society; consulting fees from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Genentech, Janssen, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck, Newave, and Pharmacyclics; and participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board at Gilead Sciences. K.P. reports grants or contracts paid to the institution from AstraZeneca and Adaptive; consulting fees from AbbVie, Adaptive, ADC, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Caribou, Fate Therapeutics, Genentech/Roche, Janssen/Pharmacyclics, Kite Pharma, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck, MorphoSys, Sana Biotechnology, and Xencor; and payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from AstraZeneca and Kite Pharma. C.S.T. reports support for this article in the form of medical writing and honoraria from Eli Lilly and Company. T.A.E. reports grants or contracts from AstraZeneca and BeiGene; consulting fees from Roche, Gilead Sciences, Kite Pharma, Janssen, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, and BeiGene; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from Roche, Gilead Sciences, Kite Pharma, Janssen, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, and BeiGene; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Roche; and participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board at Roche, Gilead Sciences, Kite Pharma, Janssen, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, and BeiGene. C.Y.C. reports research funding from BMS, Roche, AbbVie, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Lilly; and consulting/advisory/honoraria from Roche, Janssen, Gilead Sciences, AstraZeneca, Lilly, BeiGene, Menarini, Dizal Pharma, AbbVie, Genmab, and BMS. N.N.S. reports support for this article in the form of medical writing from Lilly Oncology; research support in the form of grants or contracts from Lilly Oncology, Miltenyi Biomedicine, and Genentech; consulting fees from Miltenyi Biomedicine and Lilly Oncology; participation on an advisory board at Gilead/Kite, Novartis, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, BMS/Juno, Seattle Genetics, Galapagos, BeiGene, AbbVie, and Cargo; and stock or stock options and scientific advisory board member at Tundra Therapeutics. P.G. reports grants or contracts from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BMS, and Janssen; and consulting fees and payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Galapagos, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Roche. W.J. reports support this article from Lilly; grants or contracts from AstraZeneca and BeiGene; and participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board at Lilly, AstraZeneca, and BeiGene. M.B. is a Eli Lilly and Company employee and stockholder at Lilly. B.N. reports stock or stock options from Lilly. P.A. is an employee and stockholder at Lilly. C.W. reports support for this article from, and is an employee and stockholder at, Lilly. D.W. reports support for this article, stock or stock options, and other financial interests as an employee at Lilly. L.E.R. reports research funding paid to the institution for this sponsored study from Eli Lilly and Company; grants or contracts in the form of research funding paid to the institution from Adaptive Biotechnologies, AstraZeneca, Genentech, AbbVie, Pfizer, Eli Lilly and Company, Aptose Biosciences, Dren Bio, and Qilu Puget Sound Biotherapeutics; consulting fees from AbbVie, Ascentage, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, Janssen, Eli Lilly and Company, Pharmacyclics, Pfizer, and TG Therapeutics; payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing, or educational events from AbbVie, Pharmacyclics, Dava Oncology, Curio, Medscape, and PeerView; support for attending meetings and/or travel from Eli Lilly and Company; participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board at Ascentage; and stock or stock options at Abbott Laboratories. V.G. reports a sponsored research agreement to MD Anderson from Eli Lilly and Company; consulting fees received from AbbVie; payment or a speakers’ bureaus from Dava Oncology; associate editor payments from Informa and editor-in-chief payments from Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; other financial or nonfinancial interests in the form of a sponsored research agreement from AbbVie, Acerta Pharma, AstraZeneca, Clear Creek Bio, Gilead Sciences, Eli Lilly and Company, Pharmacyclics, Sunesis, and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK); honoraria from AstraZeneca; and consultancy roles at Atomwise and Clear Creek Bio. W.G.W. reports grants or contracts in the form of research affiliations from GSK/Novartis, AbbVie, Genentech, Pharmacyclics LLC, AstraZeneca/Acerta Pharma, Gilead Sciences, BMS (Juno and Celgene), Kite Pharma, Oncternal Therapeutics Inc, Cyclacel Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Xencor, Janssen Biotech, Nurix Therapeutics, and Numab Therapeutics; and no fee collected for consulting at AbbVie, Acerta Pharma, BMS, and Cyclacel Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Jennifer R. Brown, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School, 450 Brookline Ave, Boston, MA 02215; email: jennifer_brown@dfci.harvard.edu.

References

Author notes

V.G. and W.G.W. are joint senior authors.

Eli Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the United States and the European Union and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data-sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data-sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal