During the initial identification of leukemia oncogenes in the 1980s and 1990s, the molecular biology revolution was widely expected to deliver intuitive rules of how gene regulatory networks control normal blood cell function and how mutations in key regulatory genes cause leukemia. A recurrent take-home message from research in the intervening decades, however, is a picture of daunting network complexity, involving thousands of genes and associated regulatory sequences with increasingly more exceptions to once steadfast regulatory principles, leaving the field at times bewildered.

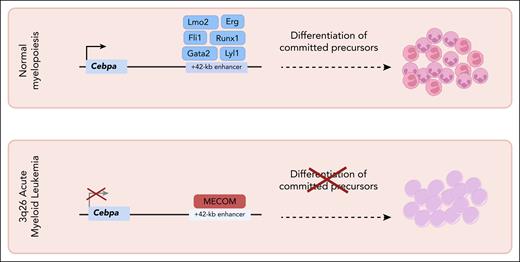

In this issue of Blood, Fleming et al1 and Pastoors et al2 take us back to beautiful simplicity, showing how a single transcriptional repressor acting on a single gene regulatory DNA region constitutes a regulatory switch that single-handedly can shift leukemic cells out of malignant proliferation into benign cellular maturation. The 2 independent studies converge on a strikingly simple mechanism whereby the MECOM protein preserves the leukemic state by binding the lineage-restricted +42-kb enhancer of the CEBPA gene. Removing that repression rapidly restores CEBPA expression, triggering terminal myeloid differentiation. The studies show that this switch can be flipped through either acute MECOM ablation or direct activation of the +42-kb enhancer, both of which induce myeloid maturation and loss of leukemic fitness.

MECOM encodes several isoforms, most notably the zinc-finger transcription factor ecotropic viral integration site 1 and is widely recognized as a key determinant of hematopoietic stem cell fitness.3 MECOM activation via chromosomal translocation in 3q26-rearranged acute myeloid leukemia (AML) represents a case of so-called enhancer hijacking, where ectopic MECOM activation causes highly aggressive disease.4-7 The CEBPA transcription factor, on the other hand, has long been recognized as a key driver of myeloid identity and differentiation, to the extent that ectopic expression of CEBPA in B-cell progenitors could redirect them into functional myeloid cells.8 Mechanistically, CEBPA expression in myeloid cells depends on a single, autonomous +42-kb enhancer, perhaps a prior clue that one regulatory element can dominate hematopoietic lineage choice.

Using an auxin-inducible degron, Pastoors et al acutely degraded MECOM in inv(3)/t(3;3) AML cells followed by subsequent profiling of nascent transcription with SLAMseq and epigenetic characterization. Upon loss of MECOM, CEBPA was identified to be one of the first and most robustly induced transcripts, associated with rapid remodeling of chromatin. Although MECOM is known to bind to the CEBPA +42-kb enhancer, crucially, this study revealed that disruption of MECOM-CTBP2 interactions (a corepressor dependency) was able to partially relieve repression. Furthermore, heterozygous deletion of the +42-kb enhancer blunted CEBPA induction and myeloid differentiation upon MECOM loss, whereas forced CEBPA expression bypassed MECOM to drive maturation.

Independently, Fleming et al used a dTAG degron to remove MECOM with minute-scale kinetics and, coupled with multiomic readouts, showed a predominantly repressive role for MECOM at chromatin. This analysis also converged on the same +42-kb enhancer as necessary and sufficient to maintain a self-renewing leukemic state. Critically, targeted activation of the +42-kb element promoted differentiation and reduced leukemia burden in vivo, arguing that this one enhancer represents an as yet unexploited therapeutic lever (see figure). Of note, the proposed regulatory network node was inferred to be operating across experimental models and primary AML samples, suggesting relevance for a substantially broader range of AML than those carrying the specific translocations.

Repression of CEBPA by MECOM in 3q26 AML leukemia cells represents a central node for therapeutic intervention. The CEBPA +42-kb enhancer is essential for normal hematopoiesis in regulating granulocytic differentiation but thought to be repressed by MECOM in hematopoietic stem cells. Downregulation of MECOM during normal stem cell differentiation results in CEBPA induction. The 3q26 chromosomal translocation co-opts the MECOM regulatory network and is associated with poor-prognosis AML. Sustained MECOM expression promotes an immature and self-renewing cell state, which can be disrupted simply by releasing the repression of the single CEPBA +42-kb enhancer, thus highlighting a key node for the development of new therapeutic strategies.

Repression of CEBPA by MECOM in 3q26 AML leukemia cells represents a central node for therapeutic intervention. The CEBPA +42-kb enhancer is essential for normal hematopoiesis in regulating granulocytic differentiation but thought to be repressed by MECOM in hematopoietic stem cells. Downregulation of MECOM during normal stem cell differentiation results in CEBPA induction. The 3q26 chromosomal translocation co-opts the MECOM regulatory network and is associated with poor-prognosis AML. Sustained MECOM expression promotes an immature and self-renewing cell state, which can be disrupted simply by releasing the repression of the single CEPBA +42-kb enhancer, thus highlighting a key node for the development of new therapeutic strategies.

These results build on long-standing work establishing the +42-kb enhancer as the gatekeeper for CEBPA expression in myeloid cells,9 and they align with broader principles of enhancer pathobiology in blood cancers. They also rationalize long-standing observations that other AML oncoproteins can impinge on CEBPA through distal elements, including the binding of RUNX1-ETO to the same enhancer.8,9

In terms of potential limitations of the studies, much of the deep mechanistic work centers on the rare subtype of 3q26/MECOM–high AML. How broadly MECOM-mediated +42-kb repression extends to MECOM-high cases without classic inv(3)/t(3;3) or to other high-risk AMLs adopting stem cell programs will require further work, including systematic patient stratification. Secondly, the elegant use of degrons minimized secondary effects but models acute repression. Feedback mechanisms, perhaps involving extrinsic inputs, may, however, shape the durability of response during more long-term repression. Furthermore, therapeutic enhancer activation or MECOM disruption using small-molecule strategies is nontrivial. Of note, the corepressor CTBP2 is clearly implicated (as shown in the articles here), but MECOM recruits broader repressive assemblies at chromatin, implying that there will be additional protein-protein interfaces to potentially expand druggability. Finally, as with any differentiation therapy, resistance and relapse remain concerns that will likely necessitate biomarker-guided approaches, including the tracking of CEBPA induction or granulocytic marker expression, as well as combination strategies based on deep mechanistic insights.

Regardless, the main take-home message of the 2 papers is disarmingly clear: a single lineage-defining enhancer can toggle leukemic self-renewal vs maturation. With clarity come experimentally tractable strategies such as MECOM degradation, disruption of MECOM-CTBP2 (or allied corepressors), and targeted activation of the +42-kb enhancer through, for example, genetic editing or locus-targeted transcriptional activation. Each can be paired with biomarker-driven monitoring of CEBPA and myeloid differentiation, echoing the lessons of acute promyelocytic leukemia but now grounded in enhancer logic. By pinpointing the +42-kb CEBPA enhancer, the 2 new studies transform at times bewilderingly complex regulatory networks into a tractable switch, possibly laying the groundwork for a next generation of differentiation therapies in high-risk AML.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

This feature is available to Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account Close Modal