Key Points

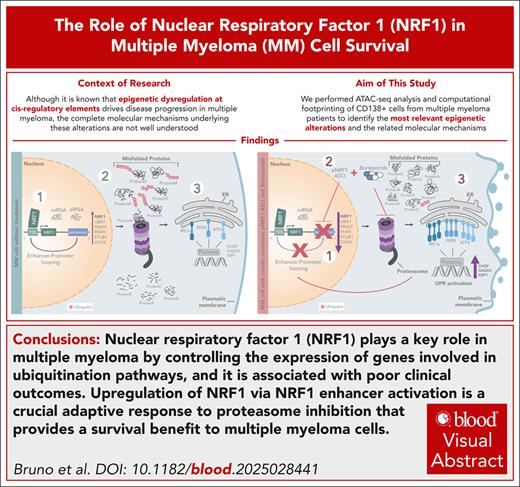

NRF1 orchestrates essential functions in MM by targeting gene promoters linked to ubiquitination and predicts poor outcome prognosis.

NRF1 upregulation serves as a crucial adaptive response under proteasome inhibition, providing a survival advantage to the cells.

Visual Abstract

Multiple myeloma (MM) continues to be an incurable malignancy, even with recent therapeutic advancements. Although epigenetic dysregulation at cis-regulatory elements is known to drive disease progression, the complete molecular mechanisms underlying these alterations are poorly understood. Using Assay for Transposase-Accessible Chromatin with high-throughput sequencing analysis combined with the computational footprinting of CD138+ cells from 55 patients with MM, we depicted the dynamic changes in chromatin accessibility during disease progression and identified nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1) as a master regulator of vital MM survival pathways. We demonstrated that NRF1 maintains proteasome homeostasis by orchestrating the ubiquitination pathway, which is essential for MM cell survival. We discovered a novel enhancer element that physically interacts with the NRF1 promoter, sustaining its expression. Targeting this enhancer RNA reduced NRF1 levels and increased tumor cell sensitivity to bortezomib (BTZ), suggesting therapeutic potential. In xenograft models, we showed that antisense oligonucleotides targeting the NRF1 enhancer, either alone or combined with BTZ, significantly decreased tumor burden and improved survival. Our findings reveal a previously unknown NRF1-dependent mechanism regulating MM cell survival and present a promising therapeutic approach through the manipulation of its regulatory network.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a hematologic disease characterized by clonal expansion of plasma cells (PCs) within the bone marrow (BM) resulting in elevated immunoglobulin levels.1-3 This pathology is usually preceded by the preneoplastic stage, monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), with a highly heterogeneous risk of progression.2,4,5 Recent evidence reveals that MM pathogenesis is more complex than previously understood, extending beyond traditional genetic explanations.5,6 Emerging research highlights how epigenetic changes can enable transcription factors (TFs) to establish novel binding sites, effectively hijacking regulatory elements to enhance tumor survival pathways.7-11

Various therapies have emerged, with bortezomib (BTZ) being a leading anti-MM agent and foundational for current and future treatments.12-14 The high production of immunoglobulin in MM makes cells dependent on proteasome activity. Proteasome inhibitors lead to the accumulation of misfolded proteins, activate endoplasmic reticulum stress, and result in MM cell death.15-17 However, acquired resistance to BTZ is observed in nearly all patients treated with this drug.18,19 Consequently, new therapeutic options are essential for overcoming resistance.

This study profiled a large cohort of MM samples using the assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing (ATAC-seq) to depict the chromatin accessibility profile from MGUS to refractory samples. Through multiomics data integration and statistical modeling, we emphasized the role of nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF1), distinct from nuclear factor erythroid 2–like 1 (NFE2L1). Notably, these genes have long shared the same name in bibliographic databases with nomenclature confusion up to the present day.20 NRF1 is an essential TF21 for early embryogenesis in mammals22 and is implicated in cell proliferation,23 cell differentiation,24 and innate antiviral immunity.22 In melanoma, NRF1 regulates CD47 expression and influences immune evasion.25

Through comprehensive analysis, we identified a distinctive NRF1-bound gene signature that links MM aggressiveness to patient mortality. Mechanistically, NRF1 depletion disrupted protein ubiquitination homeostasis and triggered endoplasmic reticulum stress, revealing its critical regulatory role. Furthermore, we demonstrated that NRF1 mediates resistance to proteasome inhibitors in both in vitro and in vivo models, establishing its potential as a therapeutic target for overcoming drug resistance.

Methods

Human specimens

To assess the pathological immune phenotype of PCs, surface and intracytoplasmic markers were identified through flow cytometry, following the methodology described by Cordone et al,26 which is the current protocol applied to patients with MM at our hospital. To differentiate between normal and neoplastic PCs, the κ-to-λ ratio was assessed on the entire CD138+ PCs and subpopulations. The CD19+ BM lymphocytes (identified by strong CD45 expression and intermediate side scatter signals) were used as internal controls for κ:λ ratio staining. For sequencing, BM aspirates were enriched for PCs by magnetic cell separation using a human CD138+ selection kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) and a MACS separator (Miltenyi Biotec). Patient clinical data are provided in supplemental Table 1, available on the Blood website.

Viral production and dCas9-KRAB system development

Glycerol stocks for dCas9-BFP-KRAB were obtained from Addgene (plasmid catalog no. 46911). To produce lentiviral particles, DNA obtained with Nucleo Bond Xtra Midi kit (Macherey-Nagel) was transfected into human embryonic kidney 293 T (HEK293-T) cells with a pPACKH1 packaging plasmid mix (System Biosciences) and Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Viral-containing supernatant was collected 48 and 72 hours after transfection and concentrated with PEG-it Virus Precipitation Solution (System Biosciences) for 18 hours at 4°C. Subsequently, the supernatant was centrifuged at 1500g for 30 minutes and stored at –80°C in cold phosphate-buffered saline. Kms18 and Kms27 were infected with dCas9-BFP-KRAB virus particles in the presence of 5 μg/mL of Polybrene for 48 hours, followed by sorting with flow cytometry using a BD FACS Melody for stable BFP expression to obtain a pure population of both cell lines. Three specific sgRNAs targeting the NRF1 gene and its enhancer were custom designed using the CHOPCHOP algorithm27 (used primers are listed in supplemental Table 3).

ATAC-seq

To profile open chromatin, we used the ATAC-seq protocol developed by Buenrostro et al28 with minor modifications. Malignant and control BM aspirates were isolated for progenitor cells by magnetic cell separation using a human CD138+ selection kit (Miltenyi Biotec) and a MACS separator (Miltenyi Biotec).

ChIP-seq

The ChIP-seq experiments for NRF1 on MM cell lines, as well as samples from MGUS and onset patients were performed following ChIPmentation protocol.29 The final libraries were controlled on 4200 TapeStation System (Agilent Technologies) and sequenced on a NextSeq 6000.

ATAC-seq and ChIP-seq data analysis

The ATAC and ChIP sequencing reads quality for each sample was assessed using FastQC v.0.11.9. Reads were aligned to the hg19 reference genome using BWA30 version 0.7.17 with default parameters. SAM files were converted into BAM format, sorted, and indexed using Samtools,31 version 1.2. Peaks were called using MACS232 version 2.2.6 (parameters: -B--SPMR--broad--broad-cutoff 0.1; ChIP-seq parameters: B--broad-q 0.1). Genome-wide coverage was saved in bedGraph format files and subsequently converted to BigWig format using bedGraphToBigWig33 version 2.10, with hg19 chromosome size reference. Blacklisted regions were filtered out with the "intersect" function of bedtools34 version 2.29.2.

PI scoring assessment and analysis

All peaks representing accessible regions in each sample of the tumor cohort were used to create a master list by concatenating, sorting, and merging them. The merging procedure was conducted using the merge function of bedtools34 version 2.29.2. The number of samples overlapping each peak in the master list was calculated and referred to as the penetrance index (PI).35

Results

Chromatin accessibility profiling of MM via ATAC-seq and footprinting analysis

We performed ATAC-seq on 55 CD138+ MM samples (Figure 1A) to identify active loci and TFs that regulate MM transformation and progression. The cohort included 27 newly diagnosed MM (NDMM) samples and 28 MM samples collected after pharmacological treatment, referred to as treated, including 11 matched NDMM-treated samples with detailed clinical and cytogenetic data (Figure 1B bottom; supplemental Table 1). We then applied TF footprinting and assessed the chromatin accessibility landscape by assigning a penetrance score,35,36 a measure of how frequently accessible sites were active across the samples (Figure 1A; supplemental Methods). ATAC-seq identified 231 017 accessible sites, averaging 24 000 peaks per sample (Figure 1A-B top) and covering about 150 megabases cumulatively (supplemental Figure 1A). Signal saturation analysis showed that 6 samples were sufficient for depicting all active promoters, whereas 55 samples did not plateau for all regulatory regions (supplemental Figure 1A), consistent with prior studies in MM and other cancers.35,37 This result suggests, as predicted by Nasser et al,38 a ratio of 1:10 for the promoter and regulatory elements, thereby providing a robust representation of the accessibility landscape.

NRF1 binding sites are highly enriched in multiple myeloma. (A) Schematic representation of the strategy used to identify TFs involved in MM disease and stratify them by their PI. (B) Heat map depicting the patient data set. Bar chart shows the number of significant accessible regions for each of the 55 samples investigated in this study and cytogenetics via fluorescence in situ hybridization coupled with clinical information (disease status, purple for NDMM and orange for treated MM; sex, light blue for male [M] and pink for female [F]; percentage of malignant PCs, purple gradient; age, green gradient) (top to bottom). (C) Heat map of unsupervised clustering analysis showing the enrichment score of each TF detected at each PI value (range, 1-55). The enrichment score represents the ratio between observed enrichment in open chromatin regions from our in-house MM cohort and expected enrichment in random chromatin accessibility sampling scenarios, with red at PI 55 and white at PI 1. Each row represents a TF, and their clustering across PI groups used the WardD method with Euclidean distance for similarity. The clustering analysis identified 3 groups: C1 containing TFs (n = 120) with heterogeneous PI, C2 containing TFs (n = 45) with high PI, and C3 containing TFs (n = 143) with low PI. The enlargement of C2 displays the detailed enrichment scores (right). (D) MSigDB pathway ontology analysis of TFs that are highly shared (PI between 36 and 55) among patients in our in-house cohort. The x-axis represents the –log10 of the FDR. (E) Motif analysis at the most penetrating loci showing the NRF1 motif (top) detected by an independent methodology using TOBIAS69 from the BAM file of each sample. Footprinting calls were performed using all 55 BAM at the most penetrant location from PI 36 to PI 55. (F) Correlation analysis of TF enrichment scores calculated at increasing population percentiles (5% increments from 5% to 100%) between our in-house MM cohort and the Lund MM cohort. The x-axis indicates the rank index for each TF assigned based on the Spearman correlation coefficient shown on the y-axis. Both cohorts have been preprocessed with the same pipeline as described in “Methods.” ATR, ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein; C1, cluster 1; FDR, false discovery rate; MSigDB, molecular signatures database; Obs/Exp, observed vs expected; PLK, polo-like kinase.

NRF1 binding sites are highly enriched in multiple myeloma. (A) Schematic representation of the strategy used to identify TFs involved in MM disease and stratify them by their PI. (B) Heat map depicting the patient data set. Bar chart shows the number of significant accessible regions for each of the 55 samples investigated in this study and cytogenetics via fluorescence in situ hybridization coupled with clinical information (disease status, purple for NDMM and orange for treated MM; sex, light blue for male [M] and pink for female [F]; percentage of malignant PCs, purple gradient; age, green gradient) (top to bottom). (C) Heat map of unsupervised clustering analysis showing the enrichment score of each TF detected at each PI value (range, 1-55). The enrichment score represents the ratio between observed enrichment in open chromatin regions from our in-house MM cohort and expected enrichment in random chromatin accessibility sampling scenarios, with red at PI 55 and white at PI 1. Each row represents a TF, and their clustering across PI groups used the WardD method with Euclidean distance for similarity. The clustering analysis identified 3 groups: C1 containing TFs (n = 120) with heterogeneous PI, C2 containing TFs (n = 45) with high PI, and C3 containing TFs (n = 143) with low PI. The enlargement of C2 displays the detailed enrichment scores (right). (D) MSigDB pathway ontology analysis of TFs that are highly shared (PI between 36 and 55) among patients in our in-house cohort. The x-axis represents the –log10 of the FDR. (E) Motif analysis at the most penetrating loci showing the NRF1 motif (top) detected by an independent methodology using TOBIAS69 from the BAM file of each sample. Footprinting calls were performed using all 55 BAM at the most penetrant location from PI 36 to PI 55. (F) Correlation analysis of TF enrichment scores calculated at increasing population percentiles (5% increments from 5% to 100%) between our in-house MM cohort and the Lund MM cohort. The x-axis indicates the rank index for each TF assigned based on the Spearman correlation coefficient shown on the y-axis. Both cohorts have been preprocessed with the same pipeline as described in “Methods.” ATR, ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein; C1, cluster 1; FDR, false discovery rate; MSigDB, molecular signatures database; Obs/Exp, observed vs expected; PLK, polo-like kinase.

As expected from previous studies,39,40 most of the detected genomic sites were uniquely active in individual samples, with only 8933 regions shared among more than 41 samples. This result highlights the significant heterogeneity in chromatin accessibility across the cohort (supplemental Figure 1A-B) and reveals a core of active loci that are essential for the MM phenotype. To further explore the regulatory landscape, we applied TF motif footprinting, which identified 171 334 distinct ∼10–base-pair motifs. These motifs were then classified into 3 primary unsupervised clusters based on their penetrance score (Figure 1C).

Cluster 1 is enriched for TF binding motifs at sites with heterogeneous (variable) penetrance (supplemental Figure 1C). This cluster includes key regulators of MM pathogenesis, such as IRF4,41 MYC,42 and NF-κB.43 Cluster 2 is enriched at highly penetrant sites and involves crucial cell survival pathways such as cell cycle regulation and ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein surveillance (Figure 1D). Cluster 3 contains unique TFs binding to private sites not further explored (supplemental Figure 1C right). NRF1 is a top regulator in cluster 2 (Figure 1C,E; supplemental Figure 1D), highlighting its role in coordinating gene expression in essential cellular processes. To validate our findings, we independently reanalyzed the largest publicly available ATAC-seq MM data set44 to date, which corroborated NRF1 enrichment at the most penetrant sites (Figure 1F).

Collectively, our integrated approach identified highly penetrant regulatory regions significantly enriched for NRF1 binding, pointing to a potential role for NRF1 in MM pathogenesis.

Expression and clinical significance of NRF1 in MM

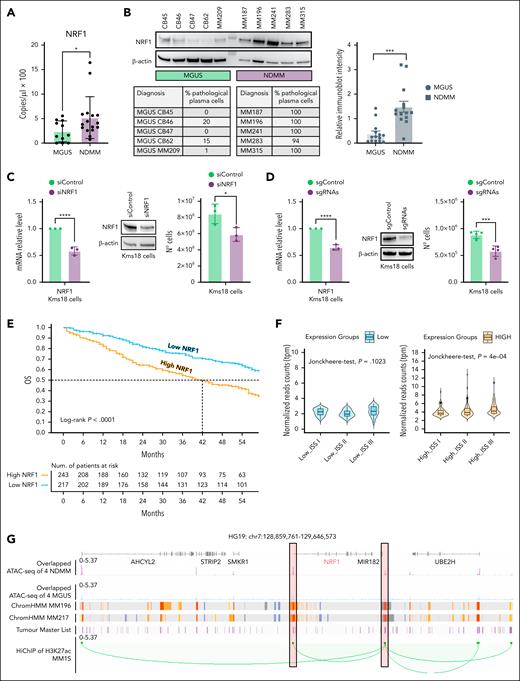

NRF1 is critical for cancer cell survival, particularly in MM (supplemental Figure 2A). We theorized that NRF1 has specific activity in MM, comparing its expression levels in premalignant states (MGUS). RNA and protein levels were higher at NDMM stages than in MGUS (Figure 2A-B; supplemental Figure 2B). Similar results were observed in the Vk∗Myc mice,45,46 a genetically engineered mouse, compared with the wild type, suggesting a potential involvement of NRF1 in neoplastic activity (supplemental Figure 2C). Accordingly, NRF1 depletion in commercial and primary MM cell lines46 led to a marked loss in cell proliferation (Figure 2C-D; supplemental Figure 2D-F).

A novel enhancer RNA sustains NRF1 transcription. (A) Digital polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results showing DNA concentration of NRF1 (copies per microliter × 100) of CD138+ PCs isolated from the BM of 11 patients with MGUS and 16 patients with NDMM. Student t test ∗P < .05. (B) Western blot (WB) analysis of NRF1 of total cellular extracts (TCEs) of CD138+ PCs purified as above for comparing expression between 5 MGUS and 5 NDMM (the percentage of mPC is showed in the corresponding table) (left). Densitometric analysis of NRF1 protein expression from the WB previously described (right). Each dot represents an individual patient. Student t test ∗∗∗P < .005. (C) Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) (left) and WB (middle) analyses of NRF1 and cell proliferation assay (right) in Kms18 MM cell line transiently transfected with siNRF1 or siControl for 72 hours. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 3 independent experiments, with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (D) qRT-PCR (left) and WB (middle) analyses of NRF1 and cell proliferation assay (right) in Kms18 MM cells stably expressing the dCas9-KRAB transcriptional repressor complex and transiently transfected with control (scramble) or NRF1 targeting sgRNAs for 72 hours. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments, with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗∗∗P < .005; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curve showing OS in the CoMMpass cohort (n = 460). Patients were stratified into 2 groups based on NRF1 expression: NRF1 high (n = 243, orange) and NRF1 low (n = 217, light blue), using the median expression value as the threshold. Patients have a maximum survival time of 60 months. (F) Box plot displaying the normalized read counts (transcripts per million [TPM]) for sample groups with low (top) and high (bottom) NRF1 expression, organized by disease stages (ISS I, ISS II, and ISS III). Statistical significance was calculated using a Kruskal-Wallis and Jonckheere-Terpstra trend tests (P value depicted in the figure). (G) Snapshots reporting genomic regions containing NRF1 promoter and its enhancer regulator. From top to bottom: gene annotation based on hg19 reference; overlapped profile of ATAC-seq from 4 NDMM samples (purple) and 4 MGUS samples (light blue); ChromHMM tracks in 2 primary MM cell lines MM196 and MM217; track showing the open chromatin sites from our in-house MM cohort (dark purple); and H3K27ac HiChIP interaction loops in MM1S (green loops). (H) Combinatorial pattern of histone marks derived from a ChromHMM model with 6 states. Heat maps display the frequency of histone modifications found in each state (left) and the probability of a state being located near another state (right). (I) qRT-PCR analysis showing the levels of eNRF1 in patients with MGUS (n = 10) and NDMM (n = 15). qRT-PCR was preceded by amplification using nested PCR. For graphical representation, the y-axis of the plot depicts the –ΔCt values with the addition of a constant (k = 15). Values were normalized to actin expression. Student t test, P value depicted in the figure. (J) Comparison of NRF1 enhancer expression levels in NDMM and matched treated samples (n = 11). Each dot represents the log-transformed normalized expression level of the NRF1 enhancer for a sample, with dashed lines connecting paired pretreated and posttreated measurements. A statistically significant reduction in NRF1 enhancer expression was observed after treatment, as determined by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P = .0068). Data points are color coded by treatment status, with red indicating pretreated and yellow indicating posttreated samples (left). Table showing the respective mPC percentages for each patient analyzed (right). (K) Expression levels of NRF1 and eNRF1 transcript (qRT-PCR) in Kms18 and Kms27 transiently transfected with si-eNRF1 or siControl (left). Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments, with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .005; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. WB analysis of NRF1 (middle) and cell proliferation assay (right) of Kms18 and Kms27 transiently transfected as previously described. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .005. Chr7, chromosome 7; H3K27ac, histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation; mPC, malignant plasma cell; mRNA, messenger RNA; N°, number of cells; sgControl, single-guide control; sgRNA, single-guide RNA; si-eNRF1, small interfering enhancer nuclear respiratory factor 1; siControl, small interfering control; TMM, trimmed mean of M-values; TSS, transcription starting site.

A novel enhancer RNA sustains NRF1 transcription. (A) Digital polymerase chain reaction (PCR) results showing DNA concentration of NRF1 (copies per microliter × 100) of CD138+ PCs isolated from the BM of 11 patients with MGUS and 16 patients with NDMM. Student t test ∗P < .05. (B) Western blot (WB) analysis of NRF1 of total cellular extracts (TCEs) of CD138+ PCs purified as above for comparing expression between 5 MGUS and 5 NDMM (the percentage of mPC is showed in the corresponding table) (left). Densitometric analysis of NRF1 protein expression from the WB previously described (right). Each dot represents an individual patient. Student t test ∗∗∗P < .005. (C) Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) (left) and WB (middle) analyses of NRF1 and cell proliferation assay (right) in Kms18 MM cell line transiently transfected with siNRF1 or siControl for 72 hours. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of 3 independent experiments, with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (D) qRT-PCR (left) and WB (middle) analyses of NRF1 and cell proliferation assay (right) in Kms18 MM cells stably expressing the dCas9-KRAB transcriptional repressor complex and transiently transfected with control (scramble) or NRF1 targeting sgRNAs for 72 hours. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments, with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗∗∗P < .005; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (E) Kaplan-Meier survival curve showing OS in the CoMMpass cohort (n = 460). Patients were stratified into 2 groups based on NRF1 expression: NRF1 high (n = 243, orange) and NRF1 low (n = 217, light blue), using the median expression value as the threshold. Patients have a maximum survival time of 60 months. (F) Box plot displaying the normalized read counts (transcripts per million [TPM]) for sample groups with low (top) and high (bottom) NRF1 expression, organized by disease stages (ISS I, ISS II, and ISS III). Statistical significance was calculated using a Kruskal-Wallis and Jonckheere-Terpstra trend tests (P value depicted in the figure). (G) Snapshots reporting genomic regions containing NRF1 promoter and its enhancer regulator. From top to bottom: gene annotation based on hg19 reference; overlapped profile of ATAC-seq from 4 NDMM samples (purple) and 4 MGUS samples (light blue); ChromHMM tracks in 2 primary MM cell lines MM196 and MM217; track showing the open chromatin sites from our in-house MM cohort (dark purple); and H3K27ac HiChIP interaction loops in MM1S (green loops). (H) Combinatorial pattern of histone marks derived from a ChromHMM model with 6 states. Heat maps display the frequency of histone modifications found in each state (left) and the probability of a state being located near another state (right). (I) qRT-PCR analysis showing the levels of eNRF1 in patients with MGUS (n = 10) and NDMM (n = 15). qRT-PCR was preceded by amplification using nested PCR. For graphical representation, the y-axis of the plot depicts the –ΔCt values with the addition of a constant (k = 15). Values were normalized to actin expression. Student t test, P value depicted in the figure. (J) Comparison of NRF1 enhancer expression levels in NDMM and matched treated samples (n = 11). Each dot represents the log-transformed normalized expression level of the NRF1 enhancer for a sample, with dashed lines connecting paired pretreated and posttreated measurements. A statistically significant reduction in NRF1 enhancer expression was observed after treatment, as determined by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P = .0068). Data points are color coded by treatment status, with red indicating pretreated and yellow indicating posttreated samples (left). Table showing the respective mPC percentages for each patient analyzed (right). (K) Expression levels of NRF1 and eNRF1 transcript (qRT-PCR) in Kms18 and Kms27 transiently transfected with si-eNRF1 or siControl (left). Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments, with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .005; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. WB analysis of NRF1 (middle) and cell proliferation assay (right) of Kms18 and Kms27 transiently transfected as previously described. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .005. Chr7, chromosome 7; H3K27ac, histone H3 lysine 27 acetylation; mPC, malignant plasma cell; mRNA, messenger RNA; N°, number of cells; sgControl, single-guide control; sgRNA, single-guide RNA; si-eNRF1, small interfering enhancer nuclear respiratory factor 1; siControl, small interfering control; TMM, trimmed mean of M-values; TSS, transcription starting site.

Subsequently, we investigated patient survival data in the MMRF-CoMMpass data set, finding that NRF1 inversely correlated with overall survival (OS) in 460 patients based on its transcript abundance (Figure 2E). Interestingly, we observed a significant increase in NRF1 expression in patients classified as International Staging System stage III (ISS III) compared with those classified as ISS I, suggesting a potential role in MM progression (Figure 2F).

Our data show that NRF1, linked to cell survival, is associated with cancer progression and may serve as a disease marker.

A novel enhancer element in sustaining NRF1 expression

To investigate the regulatory mechanisms underlying NRF1 upregulation in MM, we integrated chromatin accessibility profiling with histone mark analyses in 2 primary MM cell lines (MM196 and MM217) developed in our laboratory46 (Figure 2G). Our data showed that the NRF1 promoter is active in all samples, including patients with MM and MGUS. However, Hi-C coupled with ChIP-seq data from MM1.S cells47 identified a regulatory region with enhancer-like features looping toward the NRF1 promoter. This enhancer region, located ∼170 kilobase (kb) downstream of the NRF1 promoter and upstream of the UBE2H gene, was found open across 41 patients in our MM cohort but not in MGUS samples (Figure 2G). Interestingly, this region exhibited an enrichment proportional to the percentage of pathological cells in treated samples, whereas the NRF1 promoter remained uniformly active across all disease categories (supplemental Figure 2G). ChromHMM model,48 trained on ChIP-seq data from 2 primary MM cell lines, further confirmed the enrichment of H3K4me1-3 and H3K27me3 histone marks at this enhancer site, suggesting a configuration typical of active enhancers (Figure 2H).

Enhancer RNAs are emerging as potential therapeutic targets or biomarkers.40,49 Therefore, we hypothesized that this region might produce enhancer RNAs (eNRF1). We analyzed eNRF1 expression in patients with MGUS and NDMM, finding a trend toward increased expression associated with the disease (Figure 2I). Chromatin accessibility at the eNRF1 site was significantly decreased in 9 of the 11 matched samples after treatment (Figure 2J). This result indicates that enhancer activity is directly dependent on malignant PCs, which decline after treatment. Notably, this does not apply to samples MM_046 and MM_071, which showed varied behavior likely because of the CD138+dim50 (low) condition of MM_046 during diagnosis, preventing sequencing of a large amount of malignant plasma cells. The analysis of Vk∗Myc mice further confirmed a critical alteration in this genomic region during disease progression (supplemental Figure 2H). Notably, despite the transient nature of enhancer RNA (eRNA) with its characteristically short half-life,51,52 our data suggest an unexpectedly robust eRNA production at this locus. We then inhibited eNRF1 in Kms18 and Kms27 cells through both RNA interference and CRISPR interference (Figure 2K; supplemental Figure 2I). eNRF1 inhibition significantly reduced NRF1 transcript and protein levels, thereby decreasing cell proliferation in MM cells but not in cell lines ranked as poorly H3K27ac-enriched (supplemental Figure 2J), such as HepG2 and other tested lines (supplemental Figure 2K). Notably, we also tested the top H3K27ac-enriched cell lines, specifically breast cancer MCF7, which showed a strong decrease in NRF1 expression upon short interfering RNA–mediated eNRF1 knockdown (supplemental Figure 2K). eNRF1 specificity was confirmed by the transcriptional analysis of UBE2H, not STRIP2, aligning with HiChIP data (Figure 2G; supplemental Figure 2L).

Our findings showed that NRF1 is a key gene in the MM ecosystem, regulated by a newfound enhancer, revealing an essential mechanism for MM pathogenesis.

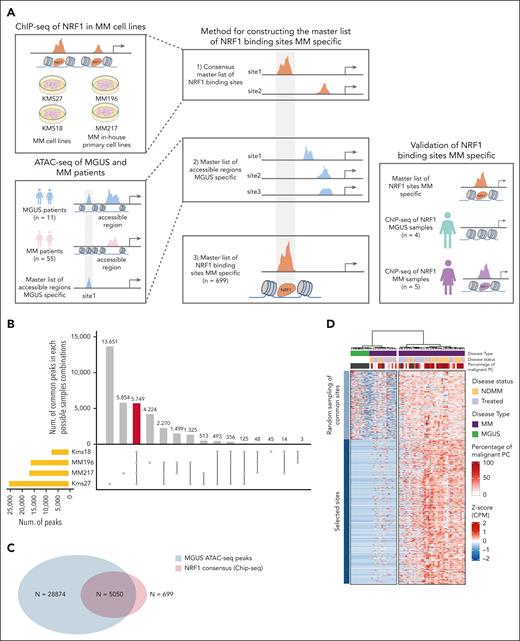

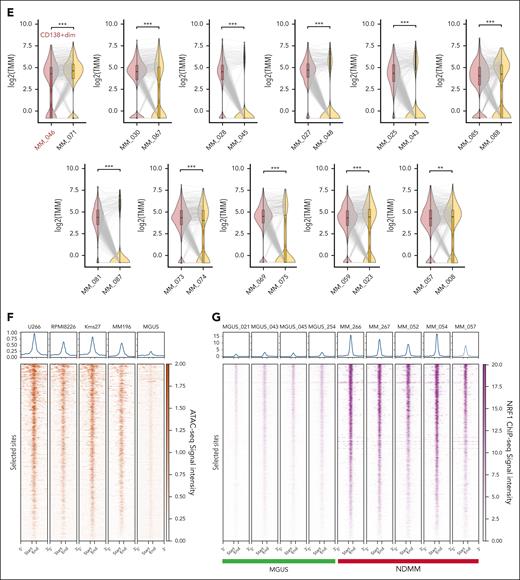

NRF1 binding at MM-specific loci

NRF1 is an essential TF (supplemental Figure 2A). We sought to identify specific NRF1-binding sites unique to MM (Figure 3A). Therefore, we performed NRF1 ChIP-seq on 2 commercial and 2 primary MM cell lines, finding 5749 common binding sites (Figure 3B). In parallel, we performed ATAC-seq on 11 MGUS samples (supplemental Figure 3A-B), integrating these into our MM chromatin accessibility map. This revealed 699 sites accessible in MM but not in MGUS (Figure 3C-D), suggesting NRF1-dependent regulatory mechanisms during MM progression. The analysis of matched NDMM and treated samples showed that 9 of the 11 patients transitioned this site to a closed state after treatment (Figure 3E). ATAC-seq on MM cell lines confirmed that these genomic regions were poorly enriched in MGUS samples compared with MM samples (Figure 3F), further establishing a disease-specific role for NRF1 binding in MM. ChIP-seq of NRF1 in both patients with MGUS and MM confirmed that NRF1 binding is significantly higher in MM than in MGUS at the selected loci (Figure 3G).

NRF1 binding sites contribute to multiple myeloma pathogenesis. (A) Schematic representation of the workflow followed in the building of the MM-specific master list of NRF1-binding sites by combining consensus NRF1 binding peaks with MGUS-specific accessible regions. (B) UpSet plot depicting the overlap of NRF1-binding sites across varied MM cell lines (Kms18, MM196, MM217, and Kms27). The bar plot above represents the number of common peaks in each intersection group, with the total number of peaks in each cell line shown in the horizontal bar chart (left). The highlighted bar indicates the intersection of consensus peaks shared by all 4 cell lines (n = 5749). (C) A Venn diagram showing the number of MM-specific NRF1 binding peaks emerged by intersecting the cumulative MGUS ATAC-seq peaks (blue) with the MM NRF1-binding sites (red). (D) Unsupervised clustering heat map showing normalized scaled accessibility counts (z score of CPM) of NRF1 MM-specific binding sites (n = 699, left bar in blue) and randomly selected NRF1-binding sites common between MM and MGUS samples (n = 300, light blue). Top bar annotations represent the disease type (MM, purple; MGUS, green), MM disease status (NDMM, orange; treated, light purple), and the percentage of malignant PCs (red-to-white gradient, 100%-0%). Accessibility data come from ATAC-seq of MM (n = 55) and MGUS (n = 11) samples. Each column corresponds to a patient sample, and the entire cohort was clustered using the Ward D method with Euclidean distance to assess similarity. (E) Violin plots comparing chromatin accessibility at NRF1 MM-specific binding sites in matched NDMM and treated samples (n = 11), based on ATAC-seq data. Each panel represents a matched pair of samples, with corresponding Wilcoxon P values indicating significant differences in chromatin accessibility of selected sites (∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .005). The y-axis of each panel shows the log-transformed CPM of ATAC-seq signal intensity. Sample MM_046 is highlighted for its peculiarity in being CD138+dim (low). (F) Heat maps (bottom) and aggregate profiles (top) showing ATAC-seq signal intensity at NRF1 MM-specific binding sites across MM cell lines (U266, RPMI8266, Kms27, and MM196) and merged MGUS (n = 11) samples. The aggregate profiles display signal intensity from 0 (weak) to 1 (strong), whereas the heat maps use a dark red to white gradient to indicate high to low accessibility. (G) Heat maps (bottom) and aggregate profiles (top) displaying ChIP-seq signal intensity at NRF1 MM-specific binding sites across NDMM (n = 5) and MGUS (n = 4) samples. The aggregate profiles display signal intensity from 1 (weak) to 15 (strong), whereas the heat maps use a dark purple to white gradient to indicate high to low NRF1 occupancy. CPM, counts per million; TMM, trimmed mean of M-values.

NRF1 binding sites contribute to multiple myeloma pathogenesis. (A) Schematic representation of the workflow followed in the building of the MM-specific master list of NRF1-binding sites by combining consensus NRF1 binding peaks with MGUS-specific accessible regions. (B) UpSet plot depicting the overlap of NRF1-binding sites across varied MM cell lines (Kms18, MM196, MM217, and Kms27). The bar plot above represents the number of common peaks in each intersection group, with the total number of peaks in each cell line shown in the horizontal bar chart (left). The highlighted bar indicates the intersection of consensus peaks shared by all 4 cell lines (n = 5749). (C) A Venn diagram showing the number of MM-specific NRF1 binding peaks emerged by intersecting the cumulative MGUS ATAC-seq peaks (blue) with the MM NRF1-binding sites (red). (D) Unsupervised clustering heat map showing normalized scaled accessibility counts (z score of CPM) of NRF1 MM-specific binding sites (n = 699, left bar in blue) and randomly selected NRF1-binding sites common between MM and MGUS samples (n = 300, light blue). Top bar annotations represent the disease type (MM, purple; MGUS, green), MM disease status (NDMM, orange; treated, light purple), and the percentage of malignant PCs (red-to-white gradient, 100%-0%). Accessibility data come from ATAC-seq of MM (n = 55) and MGUS (n = 11) samples. Each column corresponds to a patient sample, and the entire cohort was clustered using the Ward D method with Euclidean distance to assess similarity. (E) Violin plots comparing chromatin accessibility at NRF1 MM-specific binding sites in matched NDMM and treated samples (n = 11), based on ATAC-seq data. Each panel represents a matched pair of samples, with corresponding Wilcoxon P values indicating significant differences in chromatin accessibility of selected sites (∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .005). The y-axis of each panel shows the log-transformed CPM of ATAC-seq signal intensity. Sample MM_046 is highlighted for its peculiarity in being CD138+dim (low). (F) Heat maps (bottom) and aggregate profiles (top) showing ATAC-seq signal intensity at NRF1 MM-specific binding sites across MM cell lines (U266, RPMI8266, Kms27, and MM196) and merged MGUS (n = 11) samples. The aggregate profiles display signal intensity from 0 (weak) to 1 (strong), whereas the heat maps use a dark red to white gradient to indicate high to low accessibility. (G) Heat maps (bottom) and aggregate profiles (top) displaying ChIP-seq signal intensity at NRF1 MM-specific binding sites across NDMM (n = 5) and MGUS (n = 4) samples. The aggregate profiles display signal intensity from 1 (weak) to 15 (strong), whereas the heat maps use a dark purple to white gradient to indicate high to low NRF1 occupancy. CPM, counts per million; TMM, trimmed mean of M-values.

In summary, NRF1 binds to 699 MM regulatory regions, including 411 promoters. These sites lack active chromatin in MGUS samples and those with few malignant PCs.

Identification of the NRF1-dependent signature and its clinical significance

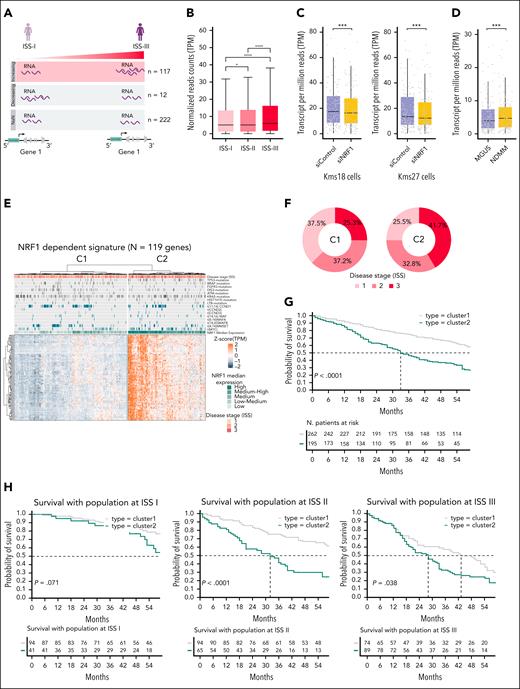

We explored NRF1 binding at key regulatory regions within 2 kb of the nearest gene. A total of 411 genes were found to have NRF1 bound at their promoters in MM, but not in premalignant lesions (supplemental Table 2). To refine our analysis, we selected genes with increased expression from early (ISS I) to advanced (ISS III) disease stages by leveraging the MMRF-CoMMpass data set (Figure 4A). After confirming that no systematic genetic bias was introduced by the selection (supplemental Figure 4A), we further filtered based on strong intergene correlations (supplemental Figure 4B). This gene selection ensured that we focused on a cohesive set of transcriptionally coregulated genes that are strongly associated with NRF1 binding and the MM aggressive phenotype.

NRF1-dependent transcriptional signature correlates with poor survival in multiple myeloma. (A) Schematic representation of the workflow used to identify genes that are regulated by NRF1 and show increased (n = 117), decreased (n = 12), or constant (n = 222) expression during disease progression. (B) Box plot reporting the normalized expression levels (TPM) of NRF1-regulated genes showing increased activity as the disease progresses through stages ISS I, ISS II, and ISS III. Paired significance between stages was computed using the Wilcoxon test (∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001). (C) Box plot depicting the TPM values of the 119 genes associated with NRF1 in Kms18 and Kms27 under siControl (violet) and siNRF1 (yellow). Wilcoxon rank-sum test (∗∗∗P < .001). (D) Box plot depicting the TPM values of the 119 genes associated with NRF1 in MGUS (violet, n = 9) and NDMM (yellow, n = 12). Wilcoxon rank-sum test (∗∗∗P < .001). (E) Heat map depicting the unsupervised clustering of the normalized scaled expression (TPM) of the highly correlated NRF1-regulated genes signature (n = 119) in the MMRF-CoMMpass cohort. Patients with MM were assigned into 2 clusters: C1 characterized by the low expression of the gene signature (blue) and C2 with high expression levels (orange). The top panel displays clinical features (ISS stage: red, ISS III; orange, ISS II; light orange, ISS I), key MM-associated mutations and translocations (dark gray, present; light gray, absent), and molecular features (NRF1 expression levels). NRF1 expression levels were categorized into 5 groups based on quantile thresholds derived from its expression distribution in the cohort (low ≤ Q20; Q20 < low_medium ≤ Q40; Q40 < medium ≥ Q60; Q60 < high_medium ≤ Q80; and high < 80). (F) Donut plots showing the percentage of patients with MM per ISS stage in C1 (left) and C2 (right) from panel E. (G) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis comparing the OS of patients with MM from the MMRF-CoMMpass cohort grouped into 2 clusters, C1 (gray) and C2 (dark green), from the panel E. C2 exhibits significantly worse survival compared with C1 (P < .0001). In the top panel, x-axis represents months, and the y-axis shows the probability of survival for each patient. The table below the plot indicates the number of patients at risk over time in each cluster. (H) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis comparing the OS of patients with MM from the MMRF-CoMMpass with patients grouped into C1 and C2 and stratified by ISS stages I, II, and III. C2 consistently shows worse survival outcomes across all ISS stages, with P values of 0.071 (ISS I), <0.0001 (ISS II), and 0.038 (ISS III). The tables below each plot indicate the number of patients at risk over time in each cluster and stage.

NRF1-dependent transcriptional signature correlates with poor survival in multiple myeloma. (A) Schematic representation of the workflow used to identify genes that are regulated by NRF1 and show increased (n = 117), decreased (n = 12), or constant (n = 222) expression during disease progression. (B) Box plot reporting the normalized expression levels (TPM) of NRF1-regulated genes showing increased activity as the disease progresses through stages ISS I, ISS II, and ISS III. Paired significance between stages was computed using the Wilcoxon test (∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001). (C) Box plot depicting the TPM values of the 119 genes associated with NRF1 in Kms18 and Kms27 under siControl (violet) and siNRF1 (yellow). Wilcoxon rank-sum test (∗∗∗P < .001). (D) Box plot depicting the TPM values of the 119 genes associated with NRF1 in MGUS (violet, n = 9) and NDMM (yellow, n = 12). Wilcoxon rank-sum test (∗∗∗P < .001). (E) Heat map depicting the unsupervised clustering of the normalized scaled expression (TPM) of the highly correlated NRF1-regulated genes signature (n = 119) in the MMRF-CoMMpass cohort. Patients with MM were assigned into 2 clusters: C1 characterized by the low expression of the gene signature (blue) and C2 with high expression levels (orange). The top panel displays clinical features (ISS stage: red, ISS III; orange, ISS II; light orange, ISS I), key MM-associated mutations and translocations (dark gray, present; light gray, absent), and molecular features (NRF1 expression levels). NRF1 expression levels were categorized into 5 groups based on quantile thresholds derived from its expression distribution in the cohort (low ≤ Q20; Q20 < low_medium ≤ Q40; Q40 < medium ≥ Q60; Q60 < high_medium ≤ Q80; and high < 80). (F) Donut plots showing the percentage of patients with MM per ISS stage in C1 (left) and C2 (right) from panel E. (G) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis comparing the OS of patients with MM from the MMRF-CoMMpass cohort grouped into 2 clusters, C1 (gray) and C2 (dark green), from the panel E. C2 exhibits significantly worse survival compared with C1 (P < .0001). In the top panel, x-axis represents months, and the y-axis shows the probability of survival for each patient. The table below the plot indicates the number of patients at risk over time in each cluster. (H) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis comparing the OS of patients with MM from the MMRF-CoMMpass with patients grouped into C1 and C2 and stratified by ISS stages I, II, and III. C2 consistently shows worse survival outcomes across all ISS stages, with P values of 0.071 (ISS I), <0.0001 (ISS II), and 0.038 (ISS III). The tables below each plot indicate the number of patients at risk over time in each cluster and stage.

This approach identified 177 NRF1-bound genes at promoters in patients with MM, but absent in MGUS. These genes showed an expression increase from ISS I to ISS III (Figure 4B). The depletion of NRF1 in MM cell lines resulted in a significant reduction in the transcriptional output of these genes (Figure 4C; supplemental Figure 4C). Conversely, gene expression levels were markedly higher in NDMM than in MGUS (Figure 4D).

We used an unsupervised clustering method to classify 457 patients from the MMRF-CoMMpass data set with the NRF1-dependent signature. This method divided patients into 2 groups, unlike the multiple groups from the genetic-dependent signature in MM transcriptome clustering53-55 (supplemental Figure 5A). Clade 2 exhibited a notably higher expression of the NRF1 signature genes compared with that of clade 1, where NRF1 expression was at its lowest (Figure 4E). The 2 clades had balanced patient percentages across ISS stages, ensuring no bias from disease severity (Figure 4F), whereas a significantly higher presence of MYC translocation and TP53 mutation in clade 2 may be linked to increased disease severity45 (supplemental Figure 5B).

Subsequently, we evaluated the association between NRF1 signature expression and survival outcomes in the MMRF-CoMMpass. Survival analysis revealed that patients with high NRF1 gene signature expression had significantly shorter OS than those with lower expression levels (log-rank P < .001; Figure 4G). To ensure the robustness of this finding, we performed a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to evaluate the impact of NRF1 gene signature expression and other relevant clinical variables (supplemental Figure 5C) that were significant at the univariate analysis on the OS (supplemental Table 2). The results confirmed that high NRF1 signature expression correlates with poor survival outcomes, regardless of other factors. Subgroup analysis by ISS stage revealed survival differences: ISS I patients showed no significant OS differences, whereas those at ISS II and III with high NRF1 expression had shorter survival than those with lower expression. (OS log-rank P < .001 for ISS II and P = .038 for ISS III; Figure 4H).

NRF1 depletion impacts ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and induces unfolded protein response activation

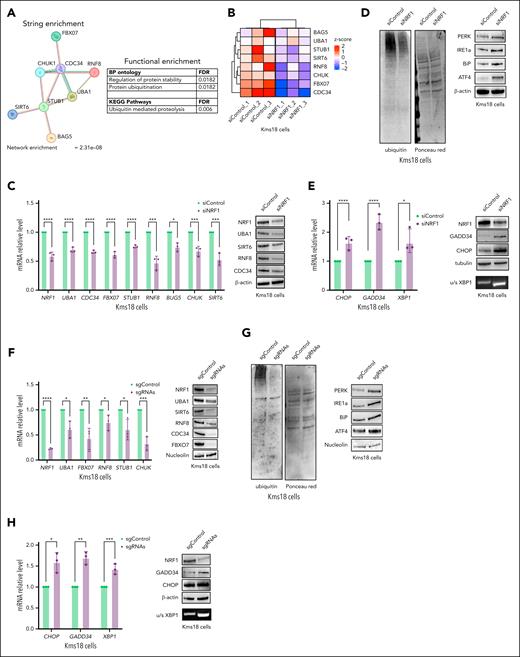

We analyzed relationships among selected genes to identify significant pathways driven by the NRF1-dependent signature, unveiling 4 main networks enriched for protein ubiquitination, RNA splicing, the cell cycle, and respiratory function (supplemental Figure 6A). Within the ubiquitination pathway, we identified a robust association among a cluster of genes that are intimately linked to the regulation of protein stability and ubiquitin function (Figure 5A) and confirmed this using RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analyses in MM cell lines (Figure 5B; supplemental Figure 6B). Furthermore, the ubiquitin-related NRF1-dependent signature was strongly enriched in patients of clade 2, previously described as having a worse prognosis (supplemental Figure 6C).

NRF1 is fundamental for ubiquitin-proteasome pathway function. (A) STRING70 enrichment regulatory network identified among the 8 NRF1 dependent genes associated with the ubiquitin pathway. Biological process and KEGG pathway analysis of 8 NRF1 dependent genes associated with the ubiquitin pathway (right). (B) Heat map depicting RNA-seq Kms18 cells at siControl (left) and siNRF1 (right). Color scheme: red for higher z score, and blue for lower z score of TPM. (C) Relative mRNA levels (qRT-PCR) of the indicated genes in Kms18 MM cell line transiently transfected with siNRF1 or siControl (left). Values were normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the standard error of 3 separate experiments. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .005; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. Representative WB analysis of Kms18 MM cell line TCEs transfected as above and probed for the indicated antibodies (right). (D) Total cell lysates from Kms18 cell depleted or not for NRF1 expression were subjected to immunoblot analysis with indicated antibodies and Ponceau staining. (E) The analysis of relative mRNA levels (qRT-PCR) (left) and WB analysis (right) for the indicated genes in Kms18 MM cell line transiently transfected with siNRF1 or siControl. Values were normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the standard error of 3 separate experiments. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (F) qRT-PCR (left) and WB analysis (right) of Kms18 MM cells stably expressing the dCas9-KRAB transcriptional repressor complex and transiently transfected with control (scramble) or targeting sgRNAs (NRF1) for the expression levels of indicated genes and antibodies. Values were normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the standard error of 3 separate experiments. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .005; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (G) Immunoblot analysis of TCE from dCas9-KRAB Kms18 MM cells transiently transfected as in panel F and analyzed for the indicated antibodies and Ponceau staining. (H) qRT-PCR (left) and WB analysis (right) of Kms18 MM cells stably expressing the dCas9-KRAB transcriptional repressor complex and transiently transfected as in panel F for the expression levels of indicated genes and antibodies. Values were normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the standard error of 3 separate experiments. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .005. (I) Proliferation assay (left), qRT-PCR (middle), and WB analysis (right) of Kms18 MM cells transiently transfected with siControl or si-NRF1-3′UTR and MycNRF1 as indicated. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the SD. Values were normalized to actin expression. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test (∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .005; ∗∗∗∗P < .001). (J) Kms18 MM cells transfected as above and analyzed for Ponceau staining, semi-qPCR (u/s XBP1), WB, and qRT-PCR for antibodies and genes specified. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments, with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the SD. ANOVA test ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (K) Proteasome activity in Kms18 and Kms27 MM cells transiently transfected with siControl or siNRF1. Proteasome-specific chymotryptic, trypsin-like, and caspase-like activities were assessed in cell extracts and expressed on a per-protein basis. The histogram shows the relative quantification of all 3 activities within each line. The average of at least 3 independent experiments (SD) is shown. Student t test, not significant. (L) Protein degradation of Kms18 MM cells transiently transfected with siControl or siNRF1. The cells were pulsed for 30 minutes with 35S amino acids and chased for the indicated times with or without MG132 (4 μM). The data showed indicate the percentage of trichloroacetic acid–insoluble radioactivity, the disappearance of which was inhibited by MG132 at any given time point, relative to the total radioactivity present at the end of the pulse. Error bars represent the standard error of 2 separate experiments. Student t test ∗P < .05. BP, biological process; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; mRNA, messenger RNA; N°, number of cells; sgControl, single-guide control; u/s XBP1, unspliced/spliced XBP1.

NRF1 is fundamental for ubiquitin-proteasome pathway function. (A) STRING70 enrichment regulatory network identified among the 8 NRF1 dependent genes associated with the ubiquitin pathway. Biological process and KEGG pathway analysis of 8 NRF1 dependent genes associated with the ubiquitin pathway (right). (B) Heat map depicting RNA-seq Kms18 cells at siControl (left) and siNRF1 (right). Color scheme: red for higher z score, and blue for lower z score of TPM. (C) Relative mRNA levels (qRT-PCR) of the indicated genes in Kms18 MM cell line transiently transfected with siNRF1 or siControl (left). Values were normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the standard error of 3 separate experiments. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .005; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. Representative WB analysis of Kms18 MM cell line TCEs transfected as above and probed for the indicated antibodies (right). (D) Total cell lysates from Kms18 cell depleted or not for NRF1 expression were subjected to immunoblot analysis with indicated antibodies and Ponceau staining. (E) The analysis of relative mRNA levels (qRT-PCR) (left) and WB analysis (right) for the indicated genes in Kms18 MM cell line transiently transfected with siNRF1 or siControl. Values were normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the standard error of 3 separate experiments. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (F) qRT-PCR (left) and WB analysis (right) of Kms18 MM cells stably expressing the dCas9-KRAB transcriptional repressor complex and transiently transfected with control (scramble) or targeting sgRNAs (NRF1) for the expression levels of indicated genes and antibodies. Values were normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the standard error of 3 separate experiments. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .005; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (G) Immunoblot analysis of TCE from dCas9-KRAB Kms18 MM cells transiently transfected as in panel F and analyzed for the indicated antibodies and Ponceau staining. (H) qRT-PCR (left) and WB analysis (right) of Kms18 MM cells stably expressing the dCas9-KRAB transcriptional repressor complex and transiently transfected as in panel F for the expression levels of indicated genes and antibodies. Values were normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the standard error of 3 separate experiments. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .005. (I) Proliferation assay (left), qRT-PCR (middle), and WB analysis (right) of Kms18 MM cells transiently transfected with siControl or si-NRF1-3′UTR and MycNRF1 as indicated. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the SD. Values were normalized to actin expression. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) test (∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .005; ∗∗∗∗P < .001). (J) Kms18 MM cells transfected as above and analyzed for Ponceau staining, semi-qPCR (u/s XBP1), WB, and qRT-PCR for antibodies and genes specified. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments, with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the SD. ANOVA test ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (K) Proteasome activity in Kms18 and Kms27 MM cells transiently transfected with siControl or siNRF1. Proteasome-specific chymotryptic, trypsin-like, and caspase-like activities were assessed in cell extracts and expressed on a per-protein basis. The histogram shows the relative quantification of all 3 activities within each line. The average of at least 3 independent experiments (SD) is shown. Student t test, not significant. (L) Protein degradation of Kms18 MM cells transiently transfected with siControl or siNRF1. The cells were pulsed for 30 minutes with 35S amino acids and chased for the indicated times with or without MG132 (4 μM). The data showed indicate the percentage of trichloroacetic acid–insoluble radioactivity, the disappearance of which was inhibited by MG132 at any given time point, relative to the total radioactivity present at the end of the pulse. Error bars represent the standard error of 2 separate experiments. Student t test ∗P < .05. BP, biological process; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; mRNA, messenger RNA; N°, number of cells; sgControl, single-guide control; u/s XBP1, unspliced/spliced XBP1.

The depletion of NRF1 diminished the transcription of ubiquitin-associated genes in the identified signature (Figure 5C; supplemental Figure 6A-D,G). Similarly, the ubiquitin complex analysis revealed a significant reduction in ubiquitinated proteins in NRF1-depleted cells. Accordingly, we observed a strong upregulation of the 3 unfolded protein response pathways upon NRF1 depletion (Figure 5D-H; supplemental Figure 6E-I) in both the interference systems, as expected when the ubiquitination process is perturbed.56 Notably, MM196 cells depleted for NRF1 showed the same results obtained above (supplemental Figure 6J-K). Strikingly, exogenous NRF1 overexpression plasmid (Myc-NRF1) was able to rescue endogenous NRF1 depletion (Figure 5I-J). Moreover, when the plasmid was transfected in Kms18 and Kms27 cells, the expression of RNA, protein levels, and the global levels of ubiquitination (supplemental Figure 6L-M) increased. These results were further validated through a rescue experiment using siNRF1 with a PERK inhibitor (supplemental Figure 6N). We then assessed NRF1’s effect on proteasome capacity by measuring 26S-specific peptidase activities57,58 in Kms18 and Kms27 extracts. NRF1 depletion did not significantly change any proteasome peptidase activity, but NRF1 inhibition significantly reduced protein degradation (Figure 5K-L; supplemental Figure 6O).

In summary, our findings reveal a novel and important mechanism by which NRF1 sustains the ubiquitination pathway and maintains unfolded protein response levels, without directly affecting proteosome activity.

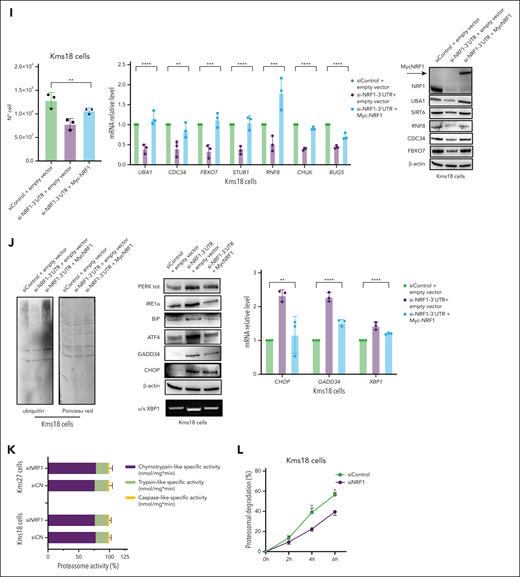

NRF1 protects MM cells against BTZ

Proteasome inhibitors have proven essential in the treatment of MM, and BTZ remains a paramount antimyeloma drug.59 Our findings suggest that NRF1 is critical in protecting MM cells from ubiquitin/proteasome stress. Consequently, we investigated whether NRF1 is involved in the response to BTZ treatment, hypothesizing that it may confer a survival advantage to the cells. Treatment with this drug in both commercial and primary MM cells resulted in a significant upregulation of NRF1, along with a concomitant increase in NRF1-dependent gene signatures linked to the ubiquitin pathway at both RNA and protein levels (Figure 6A; supplemental Figure 7A-B). This upregulation was further validated in patient-derived CD138+ cells from 9 individuals with distinct cytogenetic lesions, where NRF1 RNA levels showed a marked increase after 24 hours of BTZ exposure (Figure 6B-C) in all patient-derived cells, suggesting a linear dependency between BTZ exposure and NRF1 expression genetically independent.

NRF1 upregulation mediates adaptive resistance to proteasome inhibition. (A) qRT-PCR of the indicated genes (left) and WB analysis with the indicated antibodies (right) of Kms18 MM cells untreated or treated with 5 nM BTZ for 48 hours. qRT-PCR data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments, with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the standard error of 3 separate experiments. Student t test (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .001). (B) Schematic representation of the experimental setup for detecting NRF1 transcript levels in NDMM samples treated and untreated with BTZ. PCs (CD138+) isolated from a cohort of 9 patients with NDMM were maintained in culture for 24 hours and then untreated or treated with 5 nM BTZ for 24 hours. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of NRF1 expression levels in the cohort described in panel B. Values were normalized to actin expression. Student t test ∗∗∗∗P < .001 (left). Table showing the cytogenetic profiles detected at the time of the patient's diagnosis (right). (D) qRT-PCR analysis of the indicated genes in MM196 primary and resistant to BTZ (MM196-RS) cell lines. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .001 (left). WB analysis of TCE from primary and adapted MM196 cells to BTZ for the indicated antibodies (right). (E) Proliferation analysis at the indicated points of Kms18 MM cell transiently transfected with siControl and siNRF1 and treated or not with 5 nM BTZ. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (F) Kms18 MM cells transiently transfected with siControl or siNRF1 were treated with increasing BTZ concentrations. Cell viability and IC50 were measured after 48 hours. Values were calculated from the fitted curves. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .005. Bar plot (middle) showing IC50 levels obtained in the figure on the left. WB analysis (right) of NRF1 protein levels upon siNRF1. (G) Proliferation assay of primary MM196 and resistant MM196-RS cell lines transiently transfected with siControl or siNRF1. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; n.s., not significant.

NRF1 upregulation mediates adaptive resistance to proteasome inhibition. (A) qRT-PCR of the indicated genes (left) and WB analysis with the indicated antibodies (right) of Kms18 MM cells untreated or treated with 5 nM BTZ for 48 hours. qRT-PCR data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments, with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the standard error of 3 separate experiments. Student t test (∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .001). (B) Schematic representation of the experimental setup for detecting NRF1 transcript levels in NDMM samples treated and untreated with BTZ. PCs (CD138+) isolated from a cohort of 9 patients with NDMM were maintained in culture for 24 hours and then untreated or treated with 5 nM BTZ for 24 hours. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of NRF1 expression levels in the cohort described in panel B. Values were normalized to actin expression. Student t test ∗∗∗∗P < .001 (left). Table showing the cytogenetic profiles detected at the time of the patient's diagnosis (right). (D) qRT-PCR analysis of the indicated genes in MM196 primary and resistant to BTZ (MM196-RS) cell lines. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .001 (left). WB analysis of TCE from primary and adapted MM196 cells to BTZ for the indicated antibodies (right). (E) Proliferation analysis at the indicated points of Kms18 MM cell transiently transfected with siControl and siNRF1 and treated or not with 5 nM BTZ. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (F) Kms18 MM cells transiently transfected with siControl or siNRF1 were treated with increasing BTZ concentrations. Cell viability and IC50 were measured after 48 hours. Values were calculated from the fitted curves. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗∗P < .005. Bar plot (middle) showing IC50 levels obtained in the figure on the left. WB analysis (right) of NRF1 protein levels upon siNRF1. (G) Proliferation assay of primary MM196 and resistant MM196-RS cell lines transiently transfected with siControl or siNRF1. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. IC50, half maximal inhibitory concentration; n.s., not significant.

To further confirm these results, we took advantage of a BTZ-resistant primary MM cell line, MM196-RS, produced in our laboratory.46 In these cells, which showed an increased IC50 and higher expression of 2 resistance markers, NFE2L1 and NFE2L260,61 (supplemental Figure 7C-D), we observed a significant rise in NRF1 and its downstream gene signatures at both the RNA and protein levels compared with their drug-sensitive counterparts (Figure 6D). Notably, similar results were observed when MM cells were treated with other proteasome inhibitors. In contrast, no significant differences were detected with the treatment of thalidomide (supplemental Figure 7E). We hypothesized that inhibiting NRF1 during BTZ treatment would improve therapy efficacy. A proliferation assay showed that NRF1-depleted MM cells treated with BTZ quickly reduced IC50 (Figure 6E; supplemental Figure 7F-G) and cell numbers (Figure 6F; supplemental Figure 7H). In addition, NRF1 depletion in resistant MM196 cells demonstrated increased sensitivity to BTZ compared with the wild-type counterpart (Figure 6G). Finally, overexpressing Myc-NRF1 in NRF1-depleted Kms18 cells restored cell proliferation, as shown in supplemental Figure 7I.

These data suggest NRF1 upregulation is a key adaptive response in MM cells under proteasome inhibition, providing a survival advantage. Therefore, targeting the NRF1 pathway may improve the effectiveness of proteasome inhibitor treatments in MM.

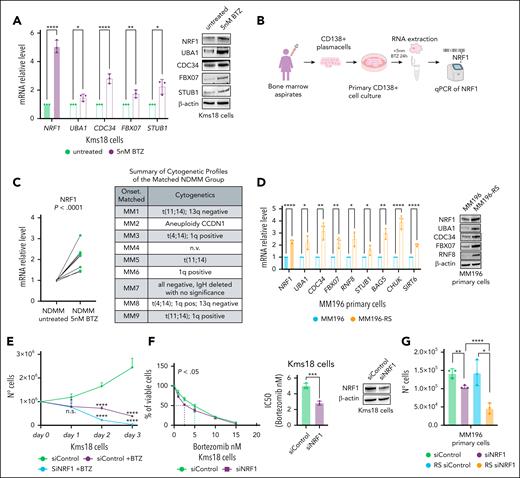

Inhibiting NRF1-related enhancer sensitizes human MM cells to BTZ in vitro and in vivo

Targeting NRF1 is challenging due to its essential cellular functions. Therefore, we decided to inhibit the eNRF1-regulating NRF1 expression to modulate transcription in MM cells, sensitizing them to BTZ. By focusing on the highly conserved NRF1 enhancer region (supplemental Figure 8A) instead of the NRF1 gene, we aimed to therapeutically manipulate this crucial regulator. BTZ treatment significantly increased eNRF1 expression in Kms18 and Kms27 cells (Figure 7A; supplemental Figure 8B). The results were corroborated in cells derived from patients, where the expression of this eRNA was observed to increase in response to pharmacological treatment (Figure 7B). Furthermore, we found that the expression of eRNA increases in MM196-RS cells compared with the sensitive counterpart (supplemental Figure 8C), and its depletion dramatically increased the sensitivity to BTZ in Kms27 cells (Figure 7C).

NRF1 enhancer inhibition sensitizes MM cells to bortezomib in vitro and in vivo. (A) qRT-PCR of Kms18 treated or not with 5 nM BTZ and analyzed for eNRF1 expression. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗∗P < .01. (B) Evaluation of mRNA level of eNRF1 in 6 patients with NDMM treated or not treated with 5 nM of BTZ for 24 hours. Student t test ∗∗∗P < .005. (C) Evaluation of Kms27 cell line proliferation transiently transfected with siControl or si-eNRF1 after BTZ treatment or no treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗∗∗P < .005; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (D) Schematic representation of in vivo experiments for silencing the NRF1 enhancer using ASO-eNRF1. (E) Tumor volumes over time in ASO scramble (blue, n = 5), ASO scramble + BTZ (purple, n = 5), ASO-eNRF1 (pink, n = 5), and ASO-eNRF1 + BTZ (green, n = 5) were calculated from caliper measurements every 3 to 4 days. Diamonds represent the timing of ASO administration. ANOVA test ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (F) Representative excised tumors (left) and tumor weight (right) at the termination of the experiments. The Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied ∗∗∗P < .001. (G) Survival analysis of previously described mice. N°, number of cells.

NRF1 enhancer inhibition sensitizes MM cells to bortezomib in vitro and in vivo. (A) qRT-PCR of Kms18 treated or not with 5 nM BTZ and analyzed for eNRF1 expression. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments and error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗∗P < .01. (B) Evaluation of mRNA level of eNRF1 in 6 patients with NDMM treated or not treated with 5 nM of BTZ for 24 hours. Student t test ∗∗∗P < .005. (C) Evaluation of Kms27 cell line proliferation transiently transfected with siControl or si-eNRF1 after BTZ treatment or no treatment. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments with values normalized to actin expression. Error bars represent the SD. Student t test ∗∗∗P < .005; ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (D) Schematic representation of in vivo experiments for silencing the NRF1 enhancer using ASO-eNRF1. (E) Tumor volumes over time in ASO scramble (blue, n = 5), ASO scramble + BTZ (purple, n = 5), ASO-eNRF1 (pink, n = 5), and ASO-eNRF1 + BTZ (green, n = 5) were calculated from caliper measurements every 3 to 4 days. Diamonds represent the timing of ASO administration. ANOVA test ∗∗∗∗P < .001. (F) Representative excised tumors (left) and tumor weight (right) at the termination of the experiments. The Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was applied ∗∗∗P < .001. (G) Survival analysis of previously described mice. N°, number of cells.

We next determined whether eNRF1 depletion could be used to inhibit MM cell growth and sensitize this disease to BTZ treatment in vivo. To this aim, we synthesized a 2′-MOE phosphorothioate–modified antisense oligos (ASO) aspecific (scramble) or against NRF1-eRNA (ASO-eNRF1) and tested them in Kms27 cells (Figure 7D). The gymnosis of ASO-eNRF1 in these cells significantly reduced eNRF1 and NRF1 expression, concomitantly decreasing NRF1 protein levels and cell growth (supplemental Figure 8D). Therefore, Kms27 cells were subcutaneously inoculated into CD-1 nude mice and treated with ASOs and subsequently with BTZ (Figure 7D). Compared with mice injected with scramble ASO, xenografted mice treated with ASO-eNRF1 showed a significant reduction in tumor growth, volume, and the weights of the excised tumor masses (Figure 7E-F), together with an increase in survival (Figure 7G). Similar results were obtained when we used MM196-RS BTZ-resistant cells, demonstrating an impact of ASO-eNRF1 on overcoming BTZ resistance (supplemental Figure 8E-H).

Overall, these results confirm the important role of NRF1 in MM growth and resistance to proteasome inhibitors and suggest the possibility of designing new specific therapeutic strategies for treating this disease.

Discussion

In this study, we have identified NRF1 as a crucial transcriptional coordinator supporting the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway by binding at the promoters of selected genes in MM. We reveal a dynamic adaptive mechanism during BTZ therapy, in which NRF1 enhances its transcriptional and translational levels, enabling MM cells to manage proteasome stress induced by proteosome inhibitor-based therapy. This response is mediated by a unique enhancer at 169 kb from the NRF1 promoter, offering insights into how malignant PCs adapt during MM development and treatment. We noted differing accessibility and transcription patterns related to eNRF1. The enhancer is transcriptionally inactive in MGUS and treated samples but becomes accessible and active in therapy-resistant and relapse samples, indicating its role in MM progression and resistance. These accessibility patterns may represent a molecular signature distinguishing disease stages and treatment responses.

Notably, the study challenges the “undruggable” TF paradigm62 by demonstrating a targeted intervention strategy. Limiting eNRF1 production could potentially weaken the survival mechanisms of MM cells without directly inhibiting the protein. Emerging targeted interventions have successfully modulated previously intractable transcriptional regulators, such as NOTCH inhibitors,63,64 and the downregulation of IKZF1 using immunomodulatory drugs,65 demonstrating diverse strategies to attenuate essential gene activity. We demonstrate in vivo that targeting the eNRF1 through ASO alone or alongside BTZ treatment significantly reduces tumor size and improves mouse survival, suggesting that targeting NRF1 disrupts ubiquitin machinery and weakens the survival of MM cells. These data support a forthcoming in vivo study in which the delivery of the ASO through the bloodstream directly reaches the tumor. The systemic delivery of ASO targeting the eNRF1 offers a promising therapeutic strategy that is further reinforced by the recent applications in targeting noncoding RNA in MM.66,67

A limitation of this study is the need to understand the mechanisms activating eNRF1. Screening NRF1-binding sites helps comprehend regulatory networks and extends insights beyond MM into oncology. In addition, further investigation into the role of methylation is warranted because NRF1 serves as a model for methylation-specific binding. Recent evidence demonstrates that the competition between NRF1 and methylation determines NRF1 binding in murine embryonic stem cells.68 This research advancement entails genome-wide analysis of methylation at NRF1-binding sites and modeling chromatin changes due to NRF1 depletion from methylation binding.

In conclusion, our findings significantly advance the understanding of MM molecular biology. By targeting the NRF1, we offer a potential strategy to enhance the effectiveness of proteasome inhibitors, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all patients and their families for their support and contributions to the research samples. The authors thank Marco Prete and Antonio Ciccotto for their constant support in engaging patients and participating in this research, Gennaro Ciliberto for mentorship, and Francesco Boccalatte and Simone Cenci for their valuable advice. These data were generated as part of the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation Personalized Medicine Initiatives (https://research.themmrf.org and www.themmrf.org).

This work was supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC; grant 15255), the Italian Ministry of Health (Institutional “Ricerca Corrente”) (M.F.), and the European Union (NextGenerationEU through the Italian Ministry of University and Research under PNRR) M4C2-I1.3, Project PE_00000019 “HEAL ITALIA”) (M.F.), CUP H83C22000550006. G.C. received funding from the AIRC and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska Curie (grant agreement number 800924).

This work is dedicated to Gian Maria Fimia and Elisabetta Mattei.

Authorship

Contribution: M.F. and G.C. conceived the rationale and developed the design of the study, supervised the analysis, obtained funding, and wrote and revised the manuscript; T.B., M.C.C., and C.C. designed and performed all the experiments; B.A. was responsible for the manipulation and production of in vivo data; F.D.N. and L.C. performed next generation sequencing experiments; G.C., C.C., and S.D.G. conducted the bioinformatics analyses; I.F. and S. Giuliani performed all the infection and the experiments by dCas9/KRAB transcriptional repressor complex; V.C. conducted all the experiments on confocal analysis; S. Gumenyuk, F.P., F.M., and A.M. provided samples from the patients with MM; B.P. performed sorting experiments of cells stably infected with dCas9-KRAB transcriptional repressor complex; R.M. performed cytogenetics analysis; S.M. was responsible for the immunofixation experiments on the patients’ samples; O.A. and S.F. provided samples of the patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance; V.D.P. performed all the experiments on digital polymerase chain reaction; P.C. and F.C. conducted proteosome activity assays; and all authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Maurizio Fanciulli, Gene Expression and Cancer Models Unit, Department of Research and Advanced Technologies Translational Research Area, IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Via E. Chianesi 53, 00144 Rome, Italy; email: maurizio.fanciulli@ifo.it; and Giacomo Corleone, Gene Expression and Cancer Models Unit, Department of Research and Advanced Technologies Translational Research Area, IRCCS Regina Elena National Cancer Institute, Via E. Chianesi 53, 00144 Rome, Italy; email: giacomo.corleone@ifo.it.

References

Author notes

T.B., M.C.C., and C.C. contributed equally to this study.

High throughput sequencing data (RNA-seq, ATAC-seq, and ChIP-seq) from this publication have been submitted to the National Cancer Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo; accession number GSE279766). All other raw data supporting the findings of this study are available at https://gbox.garr.it/garrbox/s/DiP7mWi4z2nkQ66. The ATAC-seq MM Lund data set and HiChIP data set are available through the European Genome-phenome Archive (accession numbers EGAD00001007814, and EGAD00001011138, respectively).

Codes for reproducing the analyses and figures have been deposited in https://github.com/cleliacort/NRF1_paper.git and https://zenodo.org/records/14330214.

The principal outputs obtained from the various analyses are available in supplemental Table 2. Primers, single guides, ATAC-seq indices, and antibodies are listed in the supplemental Table 3. Any further information needed to reanalyze the data presented in this article is available from the corresponding authors, Maurizio Fanciulli (maurizio.fanciulli@ifo.it) and Giacomo Corleone (giacomo.corleone@ifo.it), on request.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

There is a Blood Commentary on this article in this issue.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

![NRF1 binding sites are highly enriched in multiple myeloma. (A) Schematic representation of the strategy used to identify TFs involved in MM disease and stratify them by their PI. (B) Heat map depicting the patient data set. Bar chart shows the number of significant accessible regions for each of the 55 samples investigated in this study and cytogenetics via fluorescence in situ hybridization coupled with clinical information (disease status, purple for NDMM and orange for treated MM; sex, light blue for male [M] and pink for female [F]; percentage of malignant PCs, purple gradient; age, green gradient) (top to bottom). (C) Heat map of unsupervised clustering analysis showing the enrichment score of each TF detected at each PI value (range, 1-55). The enrichment score represents the ratio between observed enrichment in open chromatin regions from our in-house MM cohort and expected enrichment in random chromatin accessibility sampling scenarios, with red at PI 55 and white at PI 1. Each row represents a TF, and their clustering across PI groups used the WardD method with Euclidean distance for similarity. The clustering analysis identified 3 groups: C1 containing TFs (n = 120) with heterogeneous PI, C2 containing TFs (n = 45) with high PI, and C3 containing TFs (n = 143) with low PI. The enlargement of C2 displays the detailed enrichment scores (right). (D) MSigDB pathway ontology analysis of TFs that are highly shared (PI between 36 and 55) among patients in our in-house cohort. The x-axis represents the –log10 of the FDR. (E) Motif analysis at the most penetrating loci showing the NRF1 motif (top) detected by an independent methodology using TOBIAS69 from the BAM file of each sample. Footprinting calls were performed using all 55 BAM at the most penetrant location from PI 36 to PI 55. (F) Correlation analysis of TF enrichment scores calculated at increasing population percentiles (5% increments from 5% to 100%) between our in-house MM cohort and the Lund MM cohort. The x-axis indicates the rank index for each TF assigned based on the Spearman correlation coefficient shown on the y-axis. Both cohorts have been preprocessed with the same pipeline as described in “Methods.” ATR, ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein; C1, cluster 1; FDR, false discovery rate; MSigDB, molecular signatures database; Obs/Exp, observed vs expected; PLK, polo-like kinase.](https://ash.silverchair-cdn.com/ash/content_public/journal/blood/146/24/10.1182_blood.2025028441/2/m_blood_bld-2025-028441-gr1.jpeg?Expires=1768554325&Signature=YfhqNQFrXEShNw857tmG15SqRSJqaJezQDxFdM33ppyxDSuQqwa6UVnhjrnInrJVfiVw2j-DvOZuSFNzQetwD64-eP3AEQXWisd6nwVZTJFFTzCHLJLKGUQz5VYFKKiFd9~f9Sd7J0YpYet~RWssdTZuw2UbRZ5jvnhXW6gxthplITut0YZ04mNG-Qg~cvIw80TSUQkyugr3u~S5WJwuA~btKWaaNV0IkRNcsXfFms8uxH9Ez0NIpUCsNUGAlUbATIyXiqFztumuIl1E4RtlbrbfpWZ2N0mIF9H6ZI6IyynvdBgmCJw7MjkXXtFRbObUZJeVxyAoLhjgOxW84amrig__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)