Abstract

Antibodies to platelet factor 4 (PF4) have been primarily linked to classical heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (cHIT). However, during the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine program a new condition, vaccine-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (VITT), was identified, related to adenoviral-based COVID-19 vaccines. The differences between these 2 conditions, both clinically and in laboratory testing, set the scene for the development of a new rapid anti-PF4 assay that is not linked with heparin (as relevant for cHIT). Concurrently, there has been a reassessment of those cases described as autoimmune HIT. Such scenarios do not follow cHIT, but there is now a clearer differentiation of heparin-dependent and heparin-independent anti-PF4 conditions. The importance of this distinction is the identification of heparin-independent anti-PF4 antibodies in a new subgroup termed VITT-like disorder. Cases appear to be rare, precipitated by infection and in a proportion of cases, orthopaedic surgery, but are associated with high mortality and the need for a different treatment pathway, which includes immunomodulation therapy.

Learning Objectives

Determine how to divide anti-PF4 disorders into heparin dependent and heparin independent—reflecting presentation and treatment

Recognize that rapid PF4/H assays are often negative in VITT, but rapid PF4 assays may aid in the diagnosis

Introduction

Disorders associated with the presence of anti–platelet factor 4 (PF4) antibodies have undergone an evolution in definition and categorization, and our understanding is becoming clearer based on clinical presentation and laboratory diagnostics. The term autoimmune heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (aHIT) was introduced in 2011.1 It was coined after it was found that “classical” HIT (cHIT) was overdiagnosed and that only a subset of anti-PF4 antibodies result in platelet activation. However, there have been cases of continued thrombocytopenia despite stopping heparin. The use of immunoassays resulted in positive results for PF4 antibodies that were neither platelet activating nor caused classical HIT (cHIT), described as delayed onset HIT. Concurrently, within this era the term HIT paradoxes was used. These paradox situations resulted in 2 previous definitions of autoimmune HIT:

HIT associated with a proximate exposure to heparin

Spontaneous HIT (spHIT), not associated with heparin or proximate heparin exposure or other polyanionic agent2

In 2021 the new term vaccine-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis (VITT) was defined as a new condition by 3 separate groups and associated with adenoviral-based COVID-19 vaccines,3 principally ChAdOx1 but also the ad26 vaccine.4-7 There was no heparin exposure prior to acute hospital admission. The delineating features in this rare condition were low platelet counts, multisite thrombosis, especially cerebral vein thrombosis, splanchnic territory thrombosis, and arterial events at an occurrence of 20%. The condition was evident in younger individuals with no significant past medical conditions. The mortality rate was high, and laboratory analyses revealed low fibrinogen activity, markedly raised D-dimers, and a negative rapid chemiluminescent anti-immunoglobulin G (IgG) PF4/heparin assay. However, the investigation of anti-PF4 antibodies by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) identified very high optical density (OD) values (compared to those in cHIT) and subsequent confirmation that these anti-PF4 antibodies activated platelets.4-6

Three types of anti-PF4 antibodies have been proposed8:

Type 1: nonpathogenic, non-platelet activating

Type 2: heparin dependent, platelet activating

Type 3: heparin independent, platelet activating

Type 3 anti-PF4 antibodies, which were originally described in VITT, now appear to be relevant in some cases previously assigned as aHIT. Such cases require anticoagulation but also immediate therapy to reduce the impact of platelet activation and the antibody response.

CLINICAL CASE

A 31-year-old woman presented to the emergency department after experiencing 5 days of general malaise and fever. She had an isolated thrombocytopenia (51 × 109/L; normal range, 150-400 × 109/L), a raised D-dimer (>8000 ng/ml, normal range, <500 ng/ml) and reduced fibrinogen activity (0.66 g/L; normal range, 2-4 g/L). The only other laboratory abnormalities were a mildly raised C-reactive protein (22 mg/L; normal range, <0.3 mg/L) and elevated alanine transaminase (165 U/L; normal range, 4-36 U/L). Computed tomographic imaging identified pancreatic inflammation and portal vein thrombosis and low-molecular-weight heparin treatment was started. Three days later the patient became unresponsive after developing an acute right-middle cerebral artery infarction, hepatic and splenic infarction, and extensive thrombosis of the portal system, including small-bowel venous thrombosis. After an emergency resection of the ischemic bowel, intravenous (IV) unfractionated heparin and IV methylprednisolone were given, and a plasma exchange was planned. However, the patient went into cardiac arrest and resuscitation was unsuccessful.9

Autoimmune HIT

Five scenarios have been described in the past under autoimmune HIT—that is, a HIT “phenotype” but with atypia of the presentations. In comparison to cHIT, there is a higher thrombosis frequency, up to 90% in some cohorts, a lower platelet count at presentation (<30 × 109/L), and coagulopathy including disseminated intravascular thrombosis (DIC). These scenarios included the following:

Delayed-onset HIT: This refers to HIT occurring at least 5 days after stopping heparin and presentation with continued thrombocytopenia. An analysis of these cases, using the serotonin release assay, demonstrated heparin independence of serotonin release, now suggesting an anti-PF4 antibody-mediated process.10 Clinical presentations include not only pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis but also atypical thrombosis, including renal and adrenal (subsequently resulting in hemorrhage) and arterial thrombosis, strokes, myocardial infarction, and peripheral arterial thrombosis. Associated hypofibrinogenemia and microthrombosis have also been noted.

Persistent (refractory) HIT: On stopping heparin in cHIT, the platelet count would be expected to normalize within 3-4 days, with a maximum of 7 days. However, there have been cases that appear refractory, with the platelet counts taking longer than a week to normalize. Progressive thrombosis occurred in this heparin-free setting.

Heparin “flush” HIT: Some of the anti-PF4 antibodies in this situation are heparin dependent, but heparin-independent antibodies have been described.11 Interestingly, IV immunoglobulin (IVIg) has been used, but plasma exchange has been required to achieve remission.12

Fondaparinux HIT: Fondaparinux is a treatment for cHIT and as a pentasaccharide sequence of heparin, cases of HIT associated with its use were surprising. However, its presentation would appear more in keeping with aHIT and a heparin-independent mechanism.13 Such scenarios would suggest now that the fondaparinux was not directly implicated in HIT but was the therapy at the time of anti-PF4 antibody confirmation. Previous heparin use was described in these cases.

Severe HIT: This is associated with multisite arterial and venous thrombosis and heparin-independent platelet activation.

Although the idea of a HIT-like presentation with positive anti-PF4 antibodies but platelet activation independent of heparin has been present for a number of years, the following must be noted:

The diagnosis of HIT was made based on positive anti-PF4 ELISAs. Platelet activation assays are only run in superspecialist laboratories. These tests would be required to differentiate the increase in platelet reactivity due to PF4 with or without heparin. PF4-mediated platelet activation was evident with the diagnosis of VITT cases.

A rereview of “HIT” cases with atypical presentation is needed, in conjunction with an expansion of anti-PF4 antibody assays able to differentiate heparin dependence and independence.

Anti-PF4 antibody characteristics

Although both HIT and VITT demonstrate positive anti-PF4 antibodies by ELISAs, the antibodies in HIT differ from those in VITT. The VITT anti-PF4 antibodies bind to a different site on PF4 than anti-PF4 antibodies in cHIT, but both conditions result in FCRIIa receptor activation on platelets and the consequent thrombotic sequelae. In VITT, the anti-PF4 antibodies bind to the heparin-binding site, and this binding is inhibited by heparin. Conversely, polyclonal anti-PF4 antibodies in cHIT bind to amino acids at different sites to the oligoclonal/monoclonal VITT antibodies.13-16 Rapid HIT assays, such as the chemiluminescence method, were confirmed as negative in all cases of the initial VITT cohorts.4 This was because the assay is specific for PF4/heparin antibodies, whereas HIT ELISAs—either IgG or polyclonal—also identify PF4 antibodies that are heparin independent, typically with OD levels much higher than seen in cHIT cases.17

In addition to the aHIT scenarios described above, several publications before the defining of VITT mentioned “spontaneous” HIT but without proximate heparin use. These have involved mainly knee surgery, infection,2 and monoclonal gammopathy.14 Therefore, before the identification of VITT there were VITT-like presentations unrelated to adenoviral COVID-19 vaccinations. Cases of VITT-like syndrome have also been documented in conjunction with nonadenoviral COVID-19 vaccination15,16 and human papillomavirus vaccination.17 Given the rarity of presentation of these cases, it has been suggested they were spontaneous events that induced confirmational changes in PF4.

More recently, the analysis of more than 300 samples with atypical HIT have identified VITT-like anti-PF4 antibodies from cases before the COVID-19 pandemic defining a new condition, VITT-like disorder. This was aided by the development of a new anti-PF4 antibody chemiluminescence assay (AcuStar). The assay only identifies VITT anti-PF4 antibodies and not those in cHIT (PF4/heparin) on the same platform. The confirmation of platelet activation by the antibodies in patient serum was undertaken in the presence of heparin or PF4.5 In 9 cases there was no exposure to heparin or vaccination, but clinical features of supraraised D-dimers, low platelet counts, and thrombosis were noted, including 4 cases of CVT (cerebral venous thrombosis) reminiscent of VITT. Two of the cases had recurrent episodes of thrombocytopenia and thrombosis over a number of years. High OD results were documented using anti-PF4 ELISA, and all were positive with the new anti-PF4 rapid assay. Platelet activation was only evident following the addition of PF4.

To confirm the utility of this new rapid anti-PF4 assay, known VITT cases were analyzed and 99% were positive. However, 15% of this cohort were also positive in the rapid anti-PF4/heparin assay, and in functional platelet assays, heparin did not increase platelet activation.

In 188 samples with high ODs on anti-PF4/heparin ELISA, analysis on the rapid assay found that over 20% were positive to the anti-PF4, and more than 60% were positive by anti-PF4/heparin. Forty percent of the samples that were positive on the anti-PF4 rapid assay were also positive by PF4-induced platelet activation. Thus, a proportion of atypical HIT had VITT-like antibodies. Furthermore, in cHIT cases a proportion had VITT-like anti-PF4 reactivity with the addition of PF4 in functional PF4 platelet-activating antibody testing.18,19

Testing in cases with HIT or VITT-like presentation

The availability of 2 chemiluminescence assays should provide rapid results, differentiating between the 2 PF4 antigen sites corresponding to distinct sites of anti-PF4 antibody binding. These sites relate to heparin-dependent and heparin-independent platelet activation. Anti-PF4 ELISAs can also be used for diagnosis and, in specialist laboratories, as a functional assay to differentiate PF4 or heparin-dependent platelet activation.

This new condition, VITT-like disorder, associated with thrombocytopenia, supraraised D-dimer levels, and arterial or atypical venous thrombosis, is therefore associated with infection in approximately half of the cases. It presents between 5 and 14 days of the stimulating event. In one such case, adenoviral infection was the likely precipitating pathogen.18

A viral association with VITT-like disorder has recently been presented—with both cases, by chance, also having adenoviremia.20 Five and six days following symptom onset, the patients developed severe thrombocytopenia; low fibrinogen activity; very high D-dimers; and CVT, which consisted of multiple and fatal strokes, MI, and deep vein thrombosis. There was no previous heparin exposure in either patient. The laboratory analysis was in keeping with VITT-like antibodies and, in functional platelet testing, platelet activation with PF4. The anti-PF4 antibodies from both patients underwent epitope mapping, which confirmed the heparin-binding region as seen in VITT.

Availability and turnaround times for anti-PF4 assays may vary. However, VITT-like disorder should be considered based on the routine laboratory parameters as described, associated with atypical venous or arterial thrombosis that is often rapidly progressive.

Treatment

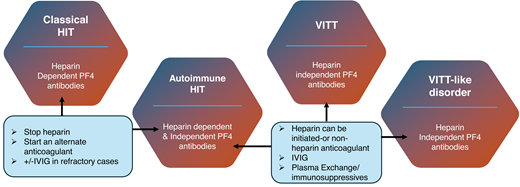

In cHIT, stopping heparin and changing to a different anticoagulant is typically associated with a rise in platelet counts and the prevention of or development/extension into thrombosis. This would suggest a more localized response with therapy. It has already been acknowledged that the acute (and often longer term) outcomes in aHIT were worse than cHIT and that the mortality for VITT was greater than 80% without treatment but still over 20% with treatment.21 Furthermore, severe thrombocytopenia (<30 × 109/L), CVT, and consequent intracranial hemorrhage carry the highest mortality and morbidity risk in VITT. Subsequent cases identified as VITT-like disorder also appear to have an acute presentation and significant mortality. In part, the mortality is related to thrombotic load. Heparin discontinuation does not appear to be necessary, but as there are alternative anticoagulants, it remains a consideration. Warfarin should be avoided in the acute setting. IVIg has been recommended for both aHIT and VITT, predominantly by providing inhibition via FCR receptors on platelets. While beneficial, platelet count normalization may take longer, and the antibody “potency” in aHIT/VITT/VITT-like disorder, along with the higher mortality, favors plasma exchange. The benefit of plasma exchange was evident in the VITT cohort—especially with multithrombosis but also in VITT-like disorder and in refractory cases of aHIT (Figure 1).20-22

Treatment in anti-F4 antibody disorders. A summary of the pathway associated with anti-PF4 disorders. In cHIT, stopping heparin and initiating an alternative anticoagulant is associated with an increment in platelet count and halting of the thrombotic risk. In aHIT, related to heparin-dependent antibodies, the pathway would be comparable to cHIT. But in those developing non–heparin-dependent antibodies, further therapy is required. It is related to progression in the immune response, requiring IVIg or occasionally additional immunomodulation, such as PEX for platelet count increase and prevention of further thrombosis. In VITT and VITT-like disorder, there is no heparin exposure. Heparin can be used, but there are alternative anticoagulants. The prompt initiation of IVIg and/or plasma exchange or alternate immunosuppressive therapy is required. *Alternative, non–heparin-based anticoagulation must be started. PEX, plasma exchange.

Treatment in anti-F4 antibody disorders. A summary of the pathway associated with anti-PF4 disorders. In cHIT, stopping heparin and initiating an alternative anticoagulant is associated with an increment in platelet count and halting of the thrombotic risk. In aHIT, related to heparin-dependent antibodies, the pathway would be comparable to cHIT. But in those developing non–heparin-dependent antibodies, further therapy is required. It is related to progression in the immune response, requiring IVIg or occasionally additional immunomodulation, such as PEX for platelet count increase and prevention of further thrombosis. In VITT and VITT-like disorder, there is no heparin exposure. Heparin can be used, but there are alternative anticoagulants. The prompt initiation of IVIg and/or plasma exchange or alternate immunosuppressive therapy is required. *Alternative, non–heparin-based anticoagulation must be started. PEX, plasma exchange.

CLINICAL CASE (continued)

Rapid HIT (PF4/heparin) analysis on chemiluminescence was negative, but anti-PF4 (HIT) ELISA was strongly positive. The patient's serum activated donor platelets in the presence of PF4, and this was inhibited with the addition of heparin. Subsequent follow-up revealed acute cytomegalovirus infection as the likely trigger for this VITT-like disorder.

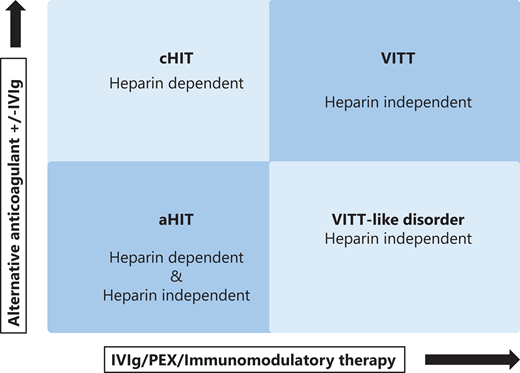

Anti-PF4 antibodies redefined

Patients with cHIT have heparin-dependent anti-PF4 antibodies; VITT patients have heparin-independent anti-PF4 antibodies. A group of aHIT patients with heparin-dependent anti-PF4 antibodies is identified. Finally, a fourth group with heparin-independent antibodies is discovered that incorporates VITT-like disorder but has a presentation comparable to spontaneous HIT (Figures 2 and 3).

Categorization of anti-PF4 antibody disorders. The 4 identified conditions related to HIT presentation. Differentiation is related to the presence of heparin-dependent or heparin- independent anti-PF4 antibodies. Classical HIT/a HIT require stopping heparin, a change in anticoagulation, and occasionally further therapy such as high-dose IVIg. Conversely, VITT or VITT-like disorder require intensive immunomodulatory therapy, such as plasma exchange (PEX).

Categorization of anti-PF4 antibody disorders. The 4 identified conditions related to HIT presentation. Differentiation is related to the presence of heparin-dependent or heparin- independent anti-PF4 antibodies. Classical HIT/a HIT require stopping heparin, a change in anticoagulation, and occasionally further therapy such as high-dose IVIg. Conversely, VITT or VITT-like disorder require intensive immunomodulatory therapy, such as plasma exchange (PEX).

Laboratory diagnosis of anti-PF4 antibody syndromes. Utilizing rapid PF4 or PF4 heparin assays, ELISAs, or confirmation by specialized platelet activation studies, the 4 scenarios are differentiated based on their relation to heparin exposure.

Laboratory diagnosis of anti-PF4 antibody syndromes. Utilizing rapid PF4 or PF4 heparin assays, ELISAs, or confirmation by specialized platelet activation studies, the 4 scenarios are differentiated based on their relation to heparin exposure.

So how should anti-PF4 antibody disorders be defined?

cHIT: heparin-dependent anti-PF4 antibodies.

Stop heparin and use an alternative anticoagulant.

aHIT: temporal association with heparin. Thrombocytopenia plus or minus thrombosis that begins or persists in the absence of heparin. Heparin-dependent and -independent anti-PF4 antibodies may be identified.

VITT: heparin independent, related to adenoviral vaccine.

HIT-like disorder/spontaneous HIT: heparin-independent anti- PF4 antibodies and no immunizing exposure to heparin.

more severe clinical phenotype requiring IVIg/plasma exchange.

VITT-like disorder/spontaneous VITT: heparin independent, 50% infection related.

More severe clinical phenotype. Requires IVIg/plasma exchange/immunosuppressive therapy.

The authors suggest, given their similarity both in clinical presentation and in laboratory parameters, group (4) and (5) should be classified together as VITT- like disorder.

With the availability of an increased repertoire of assays for diagnosis and a closer review of the clinical phenotype, leading on from VITT, there are probably 4 types of anti-PF4 conditions. The challenge is in describing spontaneous HIT, when there is no heparin exposure, or spontaneous VITT, when there is no vaccine precipitant. A redefinition of spHIT is also necessary, given its features are VITT-like. The importance of this fourth group is the recognition of acute presentation and the rapid necessity for therapy to ensure positive patient outcomes. But these scenarios appear very rare and vigilance is required. The proposal is to call this fourth group VITT-like disorder.

Conclusion

Understanding HIT and its pathophysiology, presentation, and diagnosis paved the way for the identification and management of VITT. The differences between the 2 conditions have helped clarify atypical presentations and expanded our diagnostic repertoire. Designating cases based on clinical presentation and the presence of heparin-dependent or heparin-independent anti-PF4 antibodies can facilitate a more accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatments for these rare but severe disorders. We must be sure to not only consider VITT-like disorder in our differential of thrombocytopenia and thrombosis but also follow up on patients who are likely to relapse.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Marie Scully: honoraria: Takeda, Sanofi, Alexion; advisory board: Takeda, Sanofi, Alexion; research funding: BHF, Takeda, Alexion, MRC.

William A. Lester: honoraria: Takeda, Sanofi, Alexion; advisory board: Takeda, Sanofi, Alexion.

Off-label drug use

Marie Scully: Nothing to disclose.

William A. Lester: Nothing to disclose.