Abstract

We are now a quarter of a century after the transformative impact of rituximab in improving overall survival for patients with follicular lymphoma. With a burgeoning array of effective immunochemotherapy approaches, we can now frame many patients' expectations of longevity and a “functional cure,” with survival estimates for many newly diagnosed patients comparable to age- and gender-matched populations. We highlight not just heterogeneity in disease but also in patients, which influences therapeutic decision-making in an immunochemotherapy era where progression-free survival advances are associated with efficacy-toxicity trade-offs, and no clear overall survival advantage is associated with any specific regimen. We provide the metrics that assist, prognostication both at diagnosis and after initial therapy, but we also highlight the limited long-term follow-up in institutional, population, and clinical trial data sets to inform our survival estimates. Nonetheless, the data are sufficient to empower us to reframe more optimistic conversations with our patients and the lymphoma community, discussions that engender hope and planning for a life lived long, and well, after therapy for follicular lymphoma.

Learning Objectives

Assist clinicians in framing expectations of longevity and a functional cure for many patients with newly diagnosed FL

Appreciate both patient and follicular lymphoma heterogeneity when discussing initial therapy of high tumor burden disease

Equip clinicians with metrics to assist patients with prognostication and life planning after initial immunochemotherapy

SETTING THE SCENE WITH HISTORIC CASES

A 55-year-old physician presents in 2004 with obstructive jaundice due to periportal lymphadenopathy. Core biopsy confirms follicular lymphoma and computed tomography (CT) demonstrates stage II bulky abdominal (10 × 5 cm) disease: Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) score 1. He is enrolled in a clinical trial, receiving 8 cycles of rituximab-cyclophosphamide vincristine, prednisone (R-CVP) chemotherapy. With a reduction in the sum of the product of the diameters (SPD) of 4 target lesions by only 48%, he fails to achieve CT-defined PR and is taken off the study. He receives 30 Gy abdominal radiotherapy, with a further 6 Gy to a residual fluorodeoxyglucose-avid mass, complicated by fatigue, nausea, and steatorrhea for 3 months. He remains in complete remission 20 years later, aged 75 years.

A 29-year-old woman likewise presenting with bulky stage II abdominal follicular lymphoma in 1992 receives cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) chemotherapy, obtaining complete radiologic (CT) remission. An asymptomatic relapse is noted on biannual surveillance imaging 15 years later. After an additional 4 years of observation, she receives second-line therapy with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone (R-CHOP) × 3 / R-CVP × 3 in 2011, obtaining a partial remission. She has waxing and waning abdominal disease (7 x 3 cm) in subsequent biannual imaging over 13 years. A biopsy performed during gastric surgery for weight reduction in 2023 at age 60 years, 31 years after her initial diagnosis, confirms persisting follicular lymphoma.

Introduction

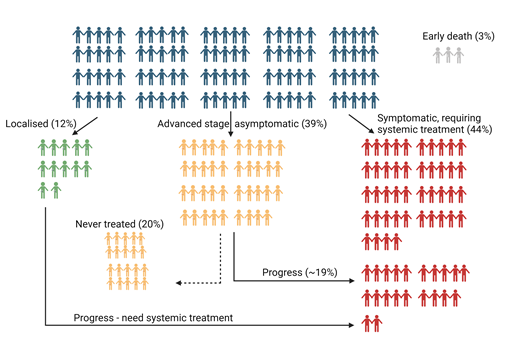

As we approach 2025, more than one quarter of a century after the transformative introduction of rituximab that improved survival for patients with follicular lymphoma (FL),1,2 we are now equipped with a burgeoning array of effective initial immunochemotherapy approaches for patients with advanced-stage (AS) disease. In this article, we argue for a rebalance in our conversations about FL with such newly diagnosed patients. We acknowledge that patients with early relapse after first-line chemoimmunotherapy, histologic transformation, or multiply relapsed disease have a poorer prognosis, and the unmet needs for this estimated one-third of patients3-5 are analyzed in accompanying manuscripts. The data on this minority, readily captured in analyses with relatively short follow-up, skew our focus to those with more aggressive phenotypes and short response durations. Motivated to develop better therapies for them in our partnerships with industry, this distracts our attention from charting the excellent outcomes for the majority of patients with newly diagnosed AS FL in 2024. We estimate one-third of patients with FL receive ≤1 line of therapy for FL in their lifetime,3 but as exemplified by these 2 case histories, another one-third of patients proceeding to second-line therapies may also survive for decades3,4,6,7 (Figure 1).6Cure, in the true Latin sense of “cura,” to heal, to restore to good health, echoed in the US National Cancer Institute dictionary of cancer terms,8 is arguably an underused word in FL where the true definition of cure in cancer remains debated and refined.9,10 Many patients will achieve a “functional cure,” whereby most are predicted to die with, rather than from, their lymphoma.11 In this review, we chart the limited long-term data that nonetheless empower us, in partnership with our patient communities, to convey optimism. We provide metrics to equip clinicians to reassure most patients, diagnosed with what may now be the most prevalent lymphoma globally, that it should not impede their ability to live a long and healthy life.

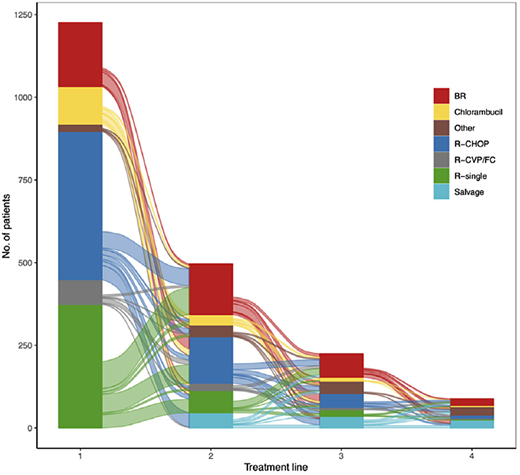

Wästerlid et al (2024),6 Sankey diagram showing the distribution and re-distribution of systemic treatment types across treatment lines 1, 2, 3, and 4 among patients diagnosed with follicular lymphoma (FL) 2007–2014, followed through 2020 in Sweden. BR, bendamustine rituximab; CVP, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone; R-FC, rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide.

Wästerlid et al (2024),6 Sankey diagram showing the distribution and re-distribution of systemic treatment types across treatment lines 1, 2, 3, and 4 among patients diagnosed with follicular lymphoma (FL) 2007–2014, followed through 2020 in Sweden. BR, bendamustine rituximab; CVP, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone; R-FC, rituximab, fludarabine, and cyclophosphamide.

Addressing the challenge of prognostication at diagnosis of advanced stage follicular lymphoma

The most common prognostic tools in clinical use, FLIPI, FLIPI-2, and PRIMA-PI, are arguably outdated in 2024. FLIPI was developed using characteristics at diagnosis collected from >4000 patients diagnosed in the pre-rituximab era and subsequently validated in cohorts treated with immunochemotherapy.12,13 It predicts an inferior 10-year overall survival (OS) of 35% for patients with ≥3 of the following variables: >4 nodal sites, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, age >60 years, stage III/IV, and hemoglobin ≤12 g/dL. Age >60 as a risk factor 3 decades ago may no longer be appropriate in 2024, where global life expectancy has risen by several years.14 Similarly, the greater diagnostic accuracy of PET-CT has resulted in significant upstaging (62%) of patients from early to AS disease.15 Attempts to further refine risk include the FLIPI-2 score, developed in newly diagnosed patients in need of treatment and externally confirmed by a cohort from the PRIMA study who received chemotherapy with or without rituximab. Additional variables of bone marrow involvement (requiring a morbid and resource-intensive bone marrow biopsy), greatest lymph node diameter, and elevated serum B2 microglobulin were added to the original age >60 years and hemoglobin ≤12 g/dL. Patients with 3 to 5 risk factors had an inferior 3-year OS of 84%.16 In contrast, the more recent PRIMA-PI uses only 2 variables—evidence of bone marrow involvement and an increased B2 microglobulin—to identify patients with an inferior 5-year progression-free survival (PFS).17 An important limitation for all 3 prognostic indices is that they were developed in patients treated with alkylator-based therapy and not those treated with bendamustine. In the more recent large GALLIUM study, bone marrow involvement was not predictive of outcome.18 None of these indices has been validated to assist in selection or adaptation of therapy for FL, and they are limited to 3-to-10-year survival predictions.

Despite the paucity of genuinely long-term data, perhaps the most affirming statement for the majority of patients who present with AS FL in 2024 is that OS is now so prolonged in the modern era that we cannot make reliable longevity estimates. However, we as treating physicians are best positioned to acknowledge this prognostic uncertainty and provide patients and their families a yardstick to assist life planning. Informed by institutional, clinical trial, and population modeling data sets,3 and taking account of the otherwise anticipated life expectancy of an individual patient, we can appropriately structure our language. Research has suggested that patients with an “incurable” cancer prefer the presentation of scenario-based estimates, with best case (the best 10%), worst case (the worst 10%), and most likely scenario (the middle 50%) of patients. They find this more helpful and more reassuring than a presentation of median survival time when explaining prognosis.19,20 Applying this approach to the fit 64-year-old (the 2017-2021 SEER database median age at diagnosis),21 we postulate that the best-case scenario for that patient is that they will have a “functional cure” and FL will have minimal impact on their life expectancy, with >20 years predicted survival. This best-case scenario is particularly plausible for women, with male sex associated with a higher rate of early FL progression and a higher excess mortality ratio.22 The worst-case scenario encompasses the approximately 10% of patients who live for less than 5 years,23-26 and our most likely scenario estimates of approximately 12-18 years survival for the middle 50% (25th to 75th percentiles) arguably reflect a functional cure for many as well.3,5,6

In framing our OS predictions this way, clinicians can help guide patients to move away from nihilistic thoughts triggered by the diagnosis of an advanced, incurable blood cancer, which create significant angst and social disruption. Such best-estimates conversations provide agency and a basis to assist patients in deciding when to start therapy, the choice of therapy, and use of ongoing treatment with antibody maintenance. Shared therapeutic decision-making, while informed by PFS data from clinical trials, is then weighted to other arguably more relevant end points to an individual patient: OS, time to next treatment (TTNT), and estimates of the efficacy-toxicity trade-offs. Robust survival predictions also assist clinicians and patients in horizon scanning and the potential sequencing of therapy within the setting of emerging immune therapies, their local health system, and social circumstances.

Survival after watch and wait for low tumor burden asymptomatic advanced-stage disease

Population estimates vary widely, but it is estimated that approximately 20% to 40% of patients with AS FL have low tumor burden asymptomatic disease and begin with a “watch-and-wait” (W&W) approach, where spontaneous regression of disease is an uncommon but recognized phenomenon.4,6 In 1 population study, 40% of W&W patients had not commenced therapy within a median follow-up of 8 years.4 One prospective UK-led trial charts the 46% not needing treatment after 3 years27 and 29% after 10 years.28 In lieu of W&W, it is important to acknowledge the durable responses for those with AS asymptomatic disease who receive single-agent rituximab. In the 7-year follow-up of the RESORT study, after 4 initial weekly doses of rituximab, 71% of patients receiving maintenance rituximab remained in first remission, as well as 37% of those assigned to a retreatment schedule.29 Similarly in the previously cited UK study, 10-year OS rates were 80% to 83% in rituximab-treated patients with a cause-specific survival of 88% to 90%, with no significant difference from the W&W population.28 The excellent tolerance, delayed commencement of chemotherapy, and low cost of rituximab monotherapy, however, make this an attractive alternative option. Another important consideration in deciding between W&W versus rituximab monotherapy strategies is health-related quality of life (HRQoL) data, with a recent 3-year longitudinal analysis in a small cohort of patients with indolent lymphoma on a W&W strategy.30 Reassuringly, findings demonstrated that patients on active surveillance had higher, clinically meaningful scores in HRQoL domains than the general population. However, emotional well-being was consistently worse, and so for those patients who are likely to “watch and worry,” single-agent rituximab may provide an attractive alternative.

What initial therapy should be recommended for a patient with symptomatic advanced-stage follicular lymphoma?

As we anchor our plans for “playing the long game” in 2024, how do we recommend therapy for a patient with AS FL in need of treatment, in an uncertain pandemic-experienced world? The literature mantra is that “FL is a heterogenous disease,” but so also are the patients. There was a 57-year span in age: 23-88 and 22-87 years in the GALLIUM and PRIMA studies, respectively. Many factors influence the decision to commence therapy, with limited application and utility of the traditional GELF or BNLI criteria outside the standardized clinical trial context.31 This combined disease and patient heterogeneity, even aided by clinical, biologic, and perhaps radiomic prognostic indices, creates uncertainty. As noted by Nobel Prize–winning scientist and prospect theorist Daniel Kahneman, humans faced with uncertain situations tend to make judgments and decisions based on prejudice and biases.32 To minimize the influence of these biases, we propose a pragmatic, data-driven approach to inform shared therapeutic decision-making.

The one certainty in first-line treatment of symptomatic AS FL is that both clinical trials23,24,33-35 and large population data sets25 show no difference in OS based on our choice of anti-CD20/ chemotherapy combination and use or not of maintenance antibody therapy (Table 1). The 7-year follow-up of GALLIUM, the largest prospective study of initial therapy of AS FL, confirms that obinutuzumab-bendamustine followed by obinutuzumab maintenance conveys the longest PFS.36 This weights our personal recommendation of this combination immunochemotherapy for younger, fitter patients, especially for those with FLIPI ≥2, who derived the greatest benefit from this combination. While lacking the same robustness, the BRIGHT33 and STIL34 studies echoed a PFS advantage of bendamustine, albeit in combination with rituximab. Without alopecia and cardiac toxicity, a bendamustine-based approach is an appealing and well-tolerated option for most fit patients aged <70 years, with an estimated 87% (95% CI 83%-91%) of patients free from next lymphoma therapy at a median 3 years of follow-up. However, a significant concern of bendamustine is the long-lasting T lymphopenia, and the higher rate of high-grade adverse events when combined with obinutuzumab.36,37 Furthermore, for the patient with B symptoms, a high lactate dehydrogenase, rapidly growing disease, and high total metabolic tumor volume in whom we suspect histologic transformation, even if the initial biopsy doesn't identify it, we prefer CHOP combined with obinutuzumab or rituximab, with comparable 3-year freedom from next lymphoma therapy of 87% and 85%, respectively. The final analysis of GALLIUM does not provide longer-term data based on the chemotherapy partner,24 but there remained no difference in the estimated 7-year OS between antibody arms.

Overall survival estimates in key Phase II and III clinical trials in firstline treatment of symptomatic advanced stage follicular lymphoma

| Study . | Regimens . | Total no. of patients . | Median follow-up (months) . | Overall survival (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marcus et al 2008 | R-CVP | 159 | 53 | 83 (4 yrs) |

| Hiddemann et al 2005 | R-CHOP | 223 | 58 | 95 (2 yrs) |

| StiL Rummel et al 2017 | R-bendamustine R-bendamustine + R maintenance | 139 595 | 34 34 | 71 (estimated 10-yr survival) NR (median) |

| BRIGHT Flinn et al 2014 Flinn et al 2019 | R-CHOP/R-CVP R-bendamustine | 206 213 | 65 65 | 81.7 (5 yrs) 85 (5 yrs) |

| FOLLO5 Luminari et al 2018 | R-CVP R-CHOP R-FM + R maintenance | 178 178 178 | 84 84 84 | 85 (8 yrs) 83 (8 yrs) 79 (8 yrs) |

| PRIMA Bachy et al 2019 | R-CHOP/CVP/FM R-CHOP/CVP/FM + R maintenance | 1018 | 118 | 80 (10 yrs) 80 (10 yrs) |

| GALLIUM Marcus et al 2017 Townsend et al 2023 | R-CHOP/CVP/bendamustine + R maintenance G-CHOP/CVP/bendamustine + G maintenance R-CHOP/R-bendamustine + R maintenance | 601 601 | 34 34 | 88.5 (7 yrs) 87.2 (7 yrs) |

| FOLLO12 Luminari et al 2021 | R-CHOP/R-bendamustine + observation R weekly × 4 ibritumomab tiuxetan + R maintenance | 393 393 | 53 53 | 98 (3 yrs) 97 (3 yrs) |

| RELEVANCE Morshhauser et al 2022 | R-CHOP/R-bendamustine + R maintenance R-lenalidomide + R maintenance | 517 513 | 38 38 | 89 (6 yrs) 89 (6 yrs) |

| Study . | Regimens . | Total no. of patients . | Median follow-up (months) . | Overall survival (%) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marcus et al 2008 | R-CVP | 159 | 53 | 83 (4 yrs) |

| Hiddemann et al 2005 | R-CHOP | 223 | 58 | 95 (2 yrs) |

| StiL Rummel et al 2017 | R-bendamustine R-bendamustine + R maintenance | 139 595 | 34 34 | 71 (estimated 10-yr survival) NR (median) |

| BRIGHT Flinn et al 2014 Flinn et al 2019 | R-CHOP/R-CVP R-bendamustine | 206 213 | 65 65 | 81.7 (5 yrs) 85 (5 yrs) |

| FOLLO5 Luminari et al 2018 | R-CVP R-CHOP R-FM + R maintenance | 178 178 178 | 84 84 84 | 85 (8 yrs) 83 (8 yrs) 79 (8 yrs) |

| PRIMA Bachy et al 2019 | R-CHOP/CVP/FM R-CHOP/CVP/FM + R maintenance | 1018 | 118 | 80 (10 yrs) 80 (10 yrs) |

| GALLIUM Marcus et al 2017 Townsend et al 2023 | R-CHOP/CVP/bendamustine + R maintenance G-CHOP/CVP/bendamustine + G maintenance R-CHOP/R-bendamustine + R maintenance | 601 601 | 34 34 | 88.5 (7 yrs) 87.2 (7 yrs) |

| FOLLO12 Luminari et al 2021 | R-CHOP/R-bendamustine + observation R weekly × 4 ibritumomab tiuxetan + R maintenance | 393 393 | 53 53 | 98 (3 yrs) 97 (3 yrs) |

| RELEVANCE Morshhauser et al 2022 | R-CHOP/R-bendamustine + R maintenance R-lenalidomide + R maintenance | 517 513 | 38 38 | 89 (6 yrs) 89 (6 yrs) |

N/A, not available; NR, not reached; yrs, years.

In contrast, for the patient aged >70 years, who has usually acquired a few comorbidities and perhaps a concerning frailty score, the morbidity and mortality associated with treatment becomes an important factor in therapeutic decision-making. The presence of comorbidities, malnutrition, and dependence in activities of daily living (ADL) or instrumental ADL independently affect outcomes in older adults with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, although most available data are extrapolated from studies in aggressive B-cell lymphoma with limited data in FL.38 In what is acknowledged as the highest-risk decade, the first 10 years after diagnosis, while the cumulative incidence of death from lymphoma was 10%, as many patients (11%) died from treatment-related or other causes. In those aged >70 years, 10-year mortality attributed to lymphoma was 25%, with 17% unrelated to lymphoma.11 This prompts a closer look at the GALLIUM data. Severe infections and fatal events during maintenance follow-up were more common in all patients receiving bendamustine (13%) than CHOP (2%) and CVP (4%). This may in part be attributable to the nonrandomized allocation to chemotherapy, where relatively more patients in the bendamustine group were >80 years of age, had poor performance status, and/or comorbidities, factors that arguably make this population more aligned with the real world. We caution citing in the tumor board, “but mine is a very fit 70-plus patient,” as this was generally the case for patients participating in the trials informing our therapeutic decision. Similarly, in the absence of prospective data confirming both comparable efficacy and reduced infection rates, we caution against the use of low-dose bendamustine in lieu of the other well-tolerated chemotherapy options, CHOP or CVP in combination with obinutuzumab/rituximab. Apart from rituximab-CVP, the TTNT in the GALLIUM study was similar across all regimens37 (Table 1).

Another option for first-line therapy is the combination of lenalidomide and rituximab (R2), with single-institution phase II data demonstrating an 8-year PFS of 65% and OS of 95%.39 Prospectively compared with R-chemotherapy in the RELEVANCE study, the 6-year PFS estimates of approximately 60% and OS of 89% for both regimens support R2 as an alternative “chemo-free” option available in the United States (Table 1). However, this combination is not toxicity-free and may be associated with cytopenias as well as gastrointestinal and cutaneous side effects.40

Maintenance anti-CD20 antibody programs demonstrate a clear PFS but no OS advantage,23,35 at a cost of increased cytopenias, infections, and transfusion demands. In the PRIMA study, with a median follow-up of 9.0 years, median TTN chemotherapy was not reached in the rituximab maintenance arm versus 9.3 years with observation. The toxicity burden of rituximab maintenance was highlighted in a meta-analysis of 2586 patients,41 with a >3-fold increase in serious infection. These risks were confirmed in a large population-based study of older patients where each additional month of rituximab maintenance increased the risk of infection, blood transfusion, and need for growth factor support by 4%, 2%, and 8%, respectively.42 In a long-term follow-up of 1643 patients, 15% of the 283 deaths observed were treatment related, undermining the goal of a functional cure.11 In this context we await the completed recruitment and results from the current PETReA study in mapping the trade-off between efficacy and toxicity of antibody maintenance in the good-risk majority of patients who achieve complete metabolic response (CMR). Meanwhile, we recommend commencement of antibody maintenance in the well and willing patient with a dynamic approach, including dose delays and cessation as dictated by tolerance, evolving infection risk, and travel priorities.

How do we prognosticate for patients after they have received initial immunochemotherapy?

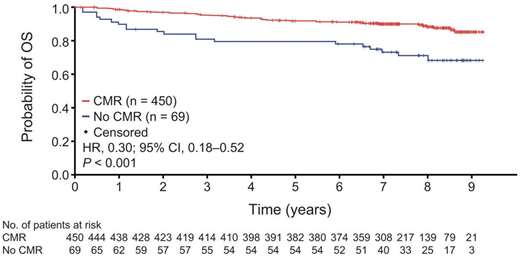

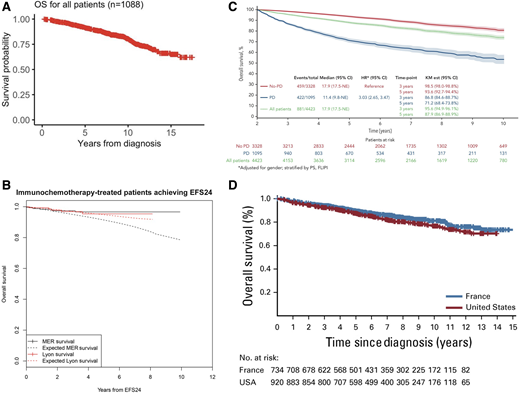

The patient who has achieved CMR after immunochemotherapy and antibody maintenance can anticipate an excellent outcome, with an estimated 90% to 91% 7-year OS regardless of antibody used (Figure 2).24,43 Collectively, institutional, population and clinical trial data suggest that we can chart a significant proportion of patients to whom we deliver a “functional cure” after initial therapy. The challenge is identifying this population when median follow-up in most data sets is less than 10 years. Similarly, there are those with late relapse who either do not need further treatment or respond to and tolerate their second line of therapy well, without appreciably impairing their life expectancy. The most recent single-institution report of long-term follow-up charts 1088 patients managed in the rituximab era, between 1998 and 2009.5 Median OS after first-line treatment was not reached, with 10-year OS estimates of 84% for patients diagnosed between 2006 and 2009 and 15-year estimates of 65% (Figure 3A). In 940 patients in a US registry, validated in 420 French patients, the 71% who remained free of an event 24 months after first-line immunochemotherapy had age- and gender-matched survival comparable to the normal US and French population (Figure 3B).44 A limitation of this study was the median 6-year follow-up, insufficient to study the impact of FL on mortality in the second decade after treatment. In a cohort of 5225 patients across 13 randomized clinical trials, the 10-year survival for patients without progression or death (68%) within 2 years was estimated to be approximately 85% (Figure 3C).45 Conversely, a Dutch population-based analysis predicting conditional relative survival for 9557 patients diagnosed during 2000-2017 suggests that excess mortality does persist, particularly for those aged >70 years, with a 5-year relative survival in older patients of 74% at diagnosis compared with 92% for those aged <60 years.26

Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS by EOI PET response status in the FL population. OS. Event-free probabilities became unreliable toward the end of the study when only around 10% to 20% of patients remained at risk. CI, confidence interval; CMR, complete metabolic response; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival.

Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS by EOI PET response status in the FL population. OS. Event-free probabilities became unreliable toward the end of the study when only around 10% to 20% of patients remained at risk. CI, confidence interval; CMR, complete metabolic response; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival.

Survival outcomes. A: OS from time of diagnosis for 1088 patients managed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center between 1998 and 2009. Outcomes by EFS 24 in patients treated with immunochemotherapy. B: Kaplan-Meier curve of subsequent overall survival after achieving EFS24 (black = MER, red = Lyon), with expected survival in the age- and sex-matched general population (dashed black = MER/United States, dashed red = Lyon/France). C: Twenty-four-month landmark Kaplan-Meier OS by POD status. All patients (A). D: Pooled analysis of US and French cohorts. Overall survival since diagnosis.

Survival outcomes. A: OS from time of diagnosis for 1088 patients managed at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center between 1998 and 2009. Outcomes by EFS 24 in patients treated with immunochemotherapy. B: Kaplan-Meier curve of subsequent overall survival after achieving EFS24 (black = MER, red = Lyon), with expected survival in the age- and sex-matched general population (dashed black = MER/United States, dashed red = Lyon/France). C: Twenty-four-month landmark Kaplan-Meier OS by POD status. All patients (A). D: Pooled analysis of US and French cohorts. Overall survival since diagnosis.

In an observational National LymphoCare Study with 2652 patients and a median 8-year follow-up, 92% (n = 2429) of patients had received first-line: of those 34% second-line, 18% third-line, and 9% fourth-line therapies.4 Swedish registry data assessing 1772 patients with a median follow-up of 7 years confirmed that 69% of patients had received first-line systemic treatment, 10% received radiotherapy only, and 20% had not received any therapy. A total of 40% of patients received a second line and 18% a third line of treatment.6 Finally, in a 20-year simulation on the basis of retrospective multicenter data of 743 patients, median OS is predicted to be 15 years: two-thirds of patients are forecast to receive ≥2 lines of therapy and one-third, ≥3 lines in their lifetime. Twenty years after diagnosis, it was estimated that 70% of patients will have died, with deaths from lymphoma and other causes equally common.3

The possibility of a functional cure for many sets the scene for tapering clinical follow-up and imaging surveillance, empowering patients to live beyond the mindset of having an incurable lymphoma. In patient-initiated follow-up as rolled out in the United Kingdom, patients are offered enrollment if appropriate after completing treatment and a defined period of clinic follow-up. They are provided with education and clear parameters to prompt contact with their clinical service to reinitiate rapid clinical review for recurrent or progressive disease. With evidence that supported self-management can improve clinical, psychosocial, and economic outcomes, further shaping of optimal strategies and the health professional support required in the lymphoma setting is needed.46,47

Finally, these encouraging survival predictions for most nonetheless chart the inadequacy of our limited follow-up to assist our youngest quartile of patients (aged ≤55 years) in their life planning.21 It is insufficient to tell them that the best estimate we can give them in 2025 is that 10 years after diagnosis they have an 80% to 85% probability of being alive and approximately 90% relative survival to an aged-matched population11,23,25,26 (Figure 3D). Similarly, providing an 8-year survival probability of 90% (95% CI 83%-94%) to the 6% diagnosed aged ≤40 years is clearly inadequate for the many who likely have young dependents.48 Until we see a clear plateau on the long-term FL survival curve, it is these very young patients who have the greatest potential reward-to-risk ratio from the introduction of novel first-line therapies such as bispecific antibodies and CAR-T aimed at deep metabolic and molecular response and potentially a “true” cure of FL.49 For this digitally informed and increasingly mobile population, contemporaneous patient- and next-of-kin-derived data collected via web or mobile technology50 may address the cost, tracking limitations, and currency of traditional institutional and population registries for this now most prevalent lymphoma. In the pursuit of living both longer and better, self- recorded diagnosis, treatment, and quality-of-life metrics may be a productive channel for these digital natives who now constitute a significant proportion of those diagnosed with FL.

Conclusion

Reflecting on the substantial improvements in survival for patients diagnosed with follicular lymphoma in the new millennium, we frame the current therapeutic landscape with a fresh perspective. The majority of patients achieve long-term, durable remissions with immunochemotherapy. With trade-offs between prolonged PFS/TTNT and increased toxicity, and no clear OS advantage to any approach, shared decision-making is essential for a nuanced therapeutic approach in 2025. Equipping clinicians with the tools and survival data to shape these discussions is critical as we champion the concept of a “functional cure” for many and encourage patients' expectations of living longer and living well. Further refinement in our ability to identify those with the highest-risk disease will be crucial in understanding who may obtain the greatest curative potential from introducing novel first-line therapies. This will also provide better clarity and reassurance to those who will fare well with current treatment approaches.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Judith Trotman: research funding to institution: BeiGene, Cellectar, Janssen, BMS.

Janlyn Falconer: no competing financial interests to declare.

Off-label drug use

Judith Trotman: nothing to disclose.

Janlyn Falconer: nothing to disclose.