Abstract

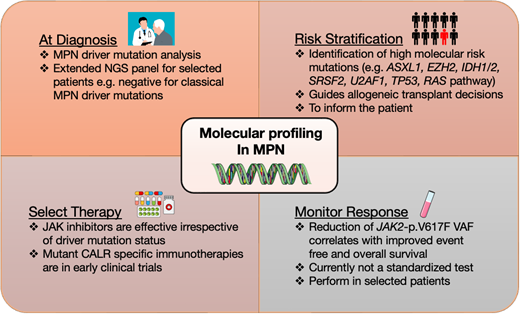

Philadelphia chromosome–negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) are a group of blood cancers that result from somatic mutations in hematopoietic stem cells, causing constitutive activation of JAK-STAT signaling pathways with consequent overproduction of 1 or more myeloid lineages. The initiating event in MPN pathogenesis is a genetic mutation, and consequently molecular profiling is central to the diagnosis, risk stratification, and, increasingly, monitoring of therapy response in persons with MPN. In this review we summarize current approaches to molecular profiling of classical MPNs (essential thrombocythemia, polycythemia vera, and myelofibrosis), using illustrative clinical case histories to demonstrate how genetic analysis is already fully integrated into MPN diagnostic classification and prognostic risk stratification. Molecular profiling can also be used in MPN to measure response to therapy both in clinical trials and increasingly in routine clinical practice. Taking a forward look, we discuss how molecular profiling in MPN might be used in the future to select specific molecularly targeted therapies and the role of additional genetic methodologies beyond mutation analysis.

Learning Objectives

Evaluate the role of different molecular approaches in MPN diagnostics

Compare different systems for prognostic risk stratification in MPN

Explain how and why molecular profiling is increasingly used to monitor response to therapy in MPN

Contrast emerging molecular diagnostic modalities with current techniques

CLINICAL CASE 1

A 49-year-old man was referred for investigation of persistent thrombocytosis 840 × 109/L identified on routine blood tests with otherwise normal blood parameters. There were no relevant symptoms or past medical history, no suggestion of an underlying reactive cause, and no findings on clinical examination. A bone marrow biopsy and molecular tests were requested.

Discussion: molecular profiling in MPN diagnostics

The classical Philadelphia chromosome–negative myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs) polycythemia vera (PV), essential thrombocythemia (ET), and primary myelofibrosis (PMF) are a group of phenotypically related clonal hematopoietic stem cell malignancies characterized by overproduction of 1 or more mature myeloid lineages. As the fundamental initiating event in MPN pathogenesis is a genetic mutation, molecular profiling is central to the diagnosis, risk management, and, increasingly, monitoring of therapy response in persons with MPN. Initiating “MPN-driver” mutations affect the JAK2, CALR, and MPL genes, typically in a mutually exclusive manner, causing constitutive activation of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway, as detailed in an excellent recent review.1 The JAK2-p.V617F mutation occurs in over 95% of PV and over 50% in ET and PMF (Table 1).1,2 One to two percent of PV patients who are JAK2-p.V617F negative have a mutation in JAK2 exon 12.1,2 Mutations in exon 9 of the CALR gene account for 30% to 40% of ET and PMF, and over 30 mutations have been described with the most common being type 1 (52 base pair [bp] deletion), followed by type 2 (5-bp insertion), with type 1- and 2-like mutations being less frequent.1,2 The least common MPN-driver mutation is in the MPL gene and is seen in 5% to 8% of ET and PMF cases.3

The World Health Organization (WHO) and International Consensus Classification (ICC) classifications4,5 incorporate detection of a clonal genetic marker as a major diagnostic criterion for all MPN subtypes (Table 2). Furthermore, a genomics-based classification of MPN has been proposed, and although this is not yet routinely applied in the clinic, the direct link between disease classification and pathobiology that genetic information provides is compelling.6 Thus, all patients being investigated for MPN should be screened for MPN-driver mutations at diagnosis, typically carried out on a peripheral blood sample. For investigation of PV, it is reasonable to carry out specific analysis for JAK2-p.V617F as an initial test, for example, using droplet digital PCR or allele-specific PCR, but for suspected ET or PMF, multiplex assays for MPN-driver mutations, typically using next-generation sequencing (NGS), are more efficient and cost effective.7

The ICC recommends a minimum sensitivity of 1% VAF as a threshold for the limit of detection to support the diagnosis of JAK2-p.V617F MPNs and between 1% and 3% in CALR and MPL MPNs.5 However, caution is required in interpreting low VAF mutations, taking into account overall clinical/laboratory context, given the high prevalence of MPN-driver mutations (particularly JAK2-p.V617F) in the general population.8 MPNs harboring more than 1 MPN-driver mutation have been reported, with single-cell sequencing demonstrating that these usually occur in different subclones.9 Therefore, in certain circumstances, for example, if a low-level JAK2 mutation is identified, testing for CALR and MPL mutations should also be considered.

In addition to the classical MPN-driver mutations, additional driver mutations occur across the MPN disease spectrum, with increased frequency in PMF, typically affecting spliceosome components (SF3B1, SRSF2, U2AF1), epigenetic regulators and transcription factors (TET2, DNMT3A, IDH1/2, EZH2, ASXL1, RUNX1, NFE2, TP53), and other signaling pathway genes (NRAS, KRAS, PTPN11, SH2B3, CBL). The spectrum of recurrent somatic gene mutations in MPN, including at progression to blast phase of MPN, was recently reviewed by Luque Paz et al1 as summarized in Table 1. Importantly, such extended molecular profiling is not required for all MPN patients at diagnosis, although this approach is useful for selected MPN patients who are negative for classical MPN-driver mutations or for prognostic risk stratification (see below).

There remains a group of 10% to 15% of ET and PMF patients who do not harbor the typical mutations in JAK2, CALR, or MPL and are termed “triple negative.”3 In these circumstances, a minority of patients may have detectable non-MPN-driver mutations that are found across a range of myeloid malignancies as well as in persons with normal blood parameters, so-called clonal hematopoiesis (CH). Interpretation of additional non-MPN-driver mutations should be made within the overall clinical context and not as definitive evidence per se of a clonal MPN (Table 1).3,10 For triple-negative patients with thrombocytosis, BCR-ABL should also be excluded. It is also important to consider that many triple-negative patients may not have a clonal disease at all, and raised blood parameters may relate to polygenic risk and/or reactive causes.11 Approximately 20% of triple-negative MPN cases have an identifiable JAK2 or MPL mutation outside the mutational hot spots that can be germline or acquired, but many have not been functionally tested (Table 3).1 Therefore, in selected cases of triple-negative MPN, more extensive genetic testing is indicated, including germline testing where relevant.7

Although a detailed review of familial MPN predisposition is beyond the scope of this review, it is important to note that there is a substantially increased risk for the development of MPN in first-degree relatives of an individual diagnosed with MPN. Such cases of familial MPN are clonal and associated with increased risk of acquiring typical somatic MPN-driver mutations.2,12 This situation should be distinguished from cases of hereditary thrombocytosis and erythrocytosis, where hematopoiesis is polyclonal.2,3,13,14 It is likely that the majority of cases of familial clustering of MPN can be explained by polygenic risk, for example, conferred by the JAK2 46/1 haplotype12,15 rather than a single actionable genetic event, and genetic counseling is usually not required in these circumstances. Nevertheless, in selected families with a strong phenotype, actionable germline predisposition alleles have been identified,12 and further genetic screening is appropriate in a minority of families.

CLINICAL CASE 1 (continued)

The bone marrow biopsy showed features consistent with MPN, including hypercellularity, megakaryocyte proliferation, clustering, and grade 1 to 2 patchy fibrosis. Cytogenetics was normal. A targeted NGS panel screening hotspot mutations in JAK2, CALR, and MPL was also negative. Subsequent testing with an extended NGS myeloid gene panel detected a noncanonical MPL-p.S264F mutation at a variant allele frequency (VAF) of 44%. The somatic nature of this mutation was confirmed by the presence of a much lower VAF of 2% in CD3+ T cells used as a surrogate for germline material. This mutation has previously been reported to occur in myeloid malignancies and was considered likely pathogenic, confirming the presence of a clonal driver mutation and meeting major criteria for a diagnosis of prefibrotic myelofibrosis.

CLINICAL CASE 2

A 57-year-old woman was referred for investigation of mild anemia, splenomegaly, and night sweats. Her blood count showed hemoglobin 11.1 g/dL, leukocytosis 13.4 × 109/L, and thrombocytosis 567 × 109/L with a leucoerythroblastic blood film and 2% circulating blast cells. The bone marrow biopsy was consistent with myelofibrosis (MF3) without excess blasts. CALR type 2 mutation was detected on an NGS MPN panel. Additional genetic tests were requested.

Discussion: molecular profiling for prognostic risk stratification in MPN

The key decision for a patient of this age with a new diagnosis of myelofibrosis is whether they should be referred for allogeneic transplant.16 This decision is, in part, based on baseline disease risk, with higher-risk patients showing more clear-cut benefit from transplant.16,17 Multiple prognostic scoring systems exist for myelofibrosis (Table 4). Using the DIPSS system, this patient would be classified as having intermediate-1 risk disease. However, extended molecular profiling can add prognostic information and is increasingly applied to refine risk stratification approaches in PMF. High molecular risk (HMR) mutations known to confer a higher prognostic risk in PMF include EZH2, IDH1, IDH2, SRSF2, and ASXL14 and are incorporated into the mutation-enhanced IPSS (MIPSS-70) score developed for transplant-age patients (≤70 years). In addition to the above considerations, the presence of the U2AF1-p.Q157 mutation is also defined as HMR in the MIPSS70+v2.0 score.18 The accumulation of a higher number of HMR mutations also increases the prognostic risk. Additional factors beyond presence of mutation alone are important, such as coexistence of certain mutations and VAF. For example, it has been suggested that an isolated ASXL1 mutation is a weak adverse prognostic marker, and its significance depends on the presence of other mutations or a VAF greater than 20%.1,19 Given the increased relevance of genetic and molecular information, the genetically inspired PSS (GIPSS) score focusing only on genetic factors was devised.20 The presence of a type 1 CALR mutation is associated with improved survival and is incorporated into the MIPSS70, MIPSS70v2.0, and GIPSS scoring systems. To specifically discriminate patients suitable for an allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, the MF transplant scoring system (MTSS) was developed and included ASXL1 mutation and a non-CALR/MPL driver as adverse markers.21 Lastly, an MPN personalized risk calculator based on clinical, cytogenetics, and molecular mutations in 33 genes provides an individualized prediction for overall survival and risk of leukemic transformation.6

RAS pathway and TP53 mutations are not considered HMR in the above scoring systems but have been associated with adverse outcomes and have also been shown to be selected for during disease progression, so presence of these mutations should warrant a careful review of individualized risk.1,22-26 Loss of the TP53 wild-type allele or gain of a second mutation on the other TP53 allele is highly prevalent at the time of progression to blast-phase MPN, especially in the presence of additional karyotypic abnormalities.1,24 For patients with myelofibrosis being considered for allogeneic transplant, an extended genetic analysis including NGS myeloid gene panel to cover HMR, RAS pathway and TP53 mutations, as well as cytogenetic analysis, will help to inform clinical decision-making regarding the risk-benefit of proceeding to transplant.7

Scoring systems integrating HMR mutations in PV and ET have also been developed;27 however, prognostic impact of mutations varies between studies in PV and ET, and extended mutation analysis is not routinely carried out in these cases.28-30 In ET, the driver-mutation status correlates with risk of complications, as incorporated into the IPSET risk score.2 While not yet routine, in selected cases of PV and ET, application of extended molecular profiling to calculate personalized risk has clinical utility.6

CLINICAL CASE 2 (continued)

Extended genetic analysis revealed ASXL1 and subclonal U2AF1-p.Q157 mutation. Karyotyping failed but SNP array analysis identified a deletion of chromosome 7. Consequently, the MIPSS70+v2.0 score was very high risk, with a predicted 10-year overall survival of <5%. Ruxolitinib was commenced and she subsequently received an allogeneic transplant and remains in remission, with 100% donor chimerism over 1 year post-transplant.

Measuring MPN-driver mutation VAF to assess disease risk and monitor response to therapy

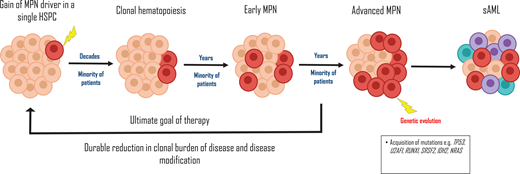

The JAK2-p.V617F mutation can be detected, often at low VAFs of <5%, in approximately 3% of asymptomatic individuals with normal blood parameters, known as clonal hematopoiesis (CH).8 As described by Luque Paz et al,1 there is a long latency period measured in decades from the time of acquisition of the JAK2-p.V617F mutation until CH is detectable, and the time required for the conversion from CH to an MPN is estimated at 5 to 15 years (Figure 1). Furthermore, progression of JAK2-p.V617F CH to MPN is not inevitable and probably only occurs during an individual's lifetime in a minority of cases, depending on the sensitivity of the assay used to detect JAK2-p.V617F.8 Two recently devised web-based tools, the MN-Predict and the CHRS calculator, can help predict the risk of development of CH to myeloid neoplasms based on an individual's age, gender, mutated CH gene, VAF (higher VAF increases risk of MPN), blood count, and biochemistry parameters.31,32 Importantly, individuals with JAK2-p.V617F CH have a higher rate of arterial and venous thromboses.33

The life history of MPNs. The gain of an MPN-driver mutation in a hematopoietic stem cell (HSPC) progenitor, such as JAK2-p.V617F, may occur as early as during embryogenesis. Over a long period of latency likely measured in decades, clonal hematopoiesis develops. The transition to an MPN ensues in a minority of patients, and subsequent acquisition of deleterious genetic mutations, eg, TP53 during clonal evolution, results in a secondary AML. The ultimate aim of therapy is disease modification, by reducing the clonal burden of disease, ie, using JAK2-p. V617F VAF as a surrogate marker. sAML, secondary acute myeloid leukemia.

The life history of MPNs. The gain of an MPN-driver mutation in a hematopoietic stem cell (HSPC) progenitor, such as JAK2-p.V617F, may occur as early as during embryogenesis. Over a long period of latency likely measured in decades, clonal hematopoiesis develops. The transition to an MPN ensues in a minority of patients, and subsequent acquisition of deleterious genetic mutations, eg, TP53 during clonal evolution, results in a secondary AML. The ultimate aim of therapy is disease modification, by reducing the clonal burden of disease, ie, using JAK2-p. V617F VAF as a surrogate marker. sAML, secondary acute myeloid leukemia.

Once MPN is established, a high JAK2-p.V617F VAF is more commonly associated with features of PV rather than ET.3 In PV, a high JAK2-p.V617F VAF of over 50% is associated with an increased risk of progression to post-PV MF1 and a higher VTE risk and is correlated with leukocytosis, a higher hematocrit, and lower platelet count.33 In myelofibrosis, however, high JAK2-p.V617F VAF predicts for improved outcome and response to JAK inhibition.34,35 MPN-driver VAF can also be unstable over time, with prognostic impact. Furthermore, complex clonal architecture can evolve during JAK2-inhibitor treatment in PMF, correlating with development of therapy resistance.36,37 In selected patients, therefore, guided by the overall clinical context, annual molecular profiling is a valuable tool to assess response to therapy and prognosis.

Although it has long been recognized that the JAK2-p.V617F VAF is reduced in some individuals with MPN during therapy, particularly with interferon, the clinical relevance of this observation has remained unclear until recently. Results from 5 years of follow-up of patients treated with ropeginteferon Alfa-2b in the PROUD-PV and CONTINUATION-PV trials showed a significantly higher molecular response rate compared with the control arm.38 In 2023, the MAJIC trial of hydroxycarbamide-resistant/intolerant PV patients showed that achieving a molecular response during therapy, defined as a reduction in JAK2-p.V617F VAF by 50% or more, strongly correlates with improved event-free and overall survival.29 These findings herald a possible transition from endpoints in MPN measured through blood counts, symptoms, and spleen length to a time where the goal of therapy is to suppress the clone, so-called disease modification, measured using MPN-driver VAF as a surrogate (Figure 1).39 Molecular monitoring of MPN-driver VAF is also predictive of post-transplantation outcomes in myelofibrosis. A detectable MPN-driver mutation at day 180 predicts a higher risk of relapse and can help to guide early intervention with donor lymphocyte infusion or cessation of immunosuppression.17 However, the assays used to measure JAK2-p.V617F VAF are currently not available in all centers and require additional standardization.28 The optimal level of JAK2-P.V617F VAF reduction and frequency of testing also needs to be determined. Consequently, it is not yet routine clinical practice to carry out serial molecular profiling in MPN patients. However, in selected cases this does help guide risk stratification and determine response to treatment and predict long-term outcomes.

Molecular profiling to identify actionable therapeutic targets in MPN

Following the discovery of the JAK2-p.V617F mutation in 2005, the subsequent clinical development of JAK inhibitor therapies has transformed the treatment landscape of MPN, which is effective irrespective of driver mutation status in MPN. Although JAK2-p.V617F selective therapies are in development, they have not yet reached the clinic. However, an exciting recent development in the MPN field relates to mutant CALR-specific immunotherapeutics. CALR encodes for a chaperone protein of the endoplasmic reticulum, and the CALR mutation generates a positively charged mutant-specific C-terminus of the protein that binds pathogenically with MPL and traffics to the cell surface.2,3 As the novel mutated C-terminus creates a tumor-specific neoantigen, it is an ideal target for immunological therapies. Therapeutic monoclonal CALR antibodies against MPN cells showed promising results in preclinical models40,41 and are now in clinical testing in multiple phase 1 studies (#NCT06034002, #NCT05444530, #NCT06150157), potentially heralding a new era in molecularly targeted therapy in MPN.

Looking forward at molecular monitoring in MPN

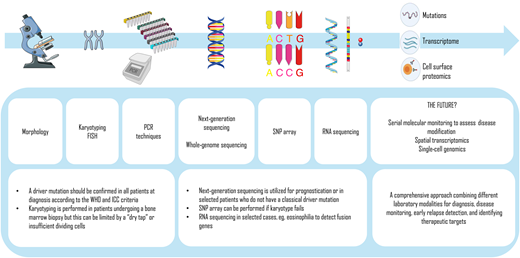

A number of additional molecular techniques are already moving into clinical diagnostics in MPN (Figure 2). For example, while conventional cytogenetic analysis has a long-established role in MPN diagnostics and prognostication (Table 4), there is a high failure rate in MF due to a “dry tap” on bone marrow aspiration. SNP-array karyotyping does not depend on live, dividing cells and has a higher bp resolution, enabling analysis of copy number variants and copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity. A recent study used SNP-array karyotyping to discover a recurrent pattern of chromothripsis leading to amplification of a region of chromosome 21 (chr21amp) with consequent overexpression of DYRK1A (serine threonine kinase and transcription factor) in blast-phase MPNs, an actionable therapeutic target in this area of unmet clinical need.42 RNA sequencing is also emerging as a promising approach in detecting fusion genes and identifying actionable genetic events.43 Whole-genome sequencing is now more routinely available as a diagnostic utility for comprehensive genome-wide driver mutation profiling, including detection of copy number alterations, fusion genes, and germline predisposition alleles.3

Laboratory techniques used for the diagnostics and prognostication of MPNs and the future. FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Laboratory techniques used for the diagnostics and prognostication of MPNs and the future. FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

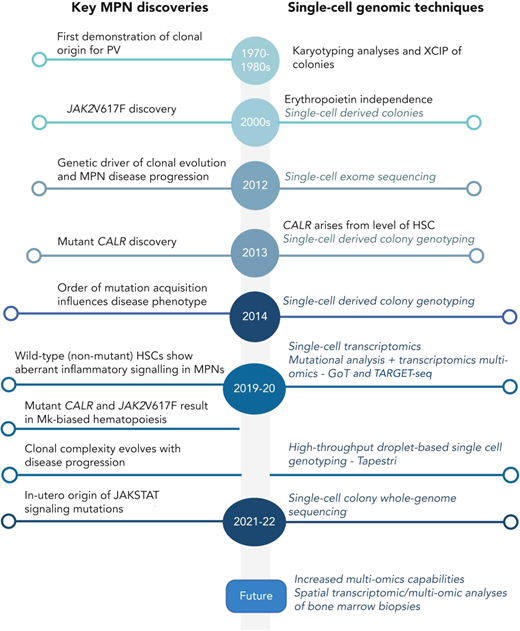

Single-cell technologies have a long history of providing insights into the pathogenesis and evolution of MPNs (Figure 3).44 In the past few years, a number of groundbreaking discoveries have been made using single-cell methods, including a description of the importance of the order of mutation acquisition and association with disease phenotype45 and a description of the long “life history” of MPN development.46,47 Multiomic single-cell analyses can now combine single-cell genotyping with RNA-sequencing and/or genetic analysis, and also with spatial resolution, providing new insights into disease biology.24,48 Single-cell genotyping of CD34+ cells from patients treated with ruxolitinib on the MAJIC-PV study demonstrated how JAK2 inhibitor therapy could eradicate MPN stem/progenitor cells.29 This highlights how these new technologies might be set for clinical implementation in the coming years, keeping MPN at the cutting edge of the application of molecular profiling in the clinic.

Timeline of key discoveries in MPNs and single-cell methodologies. Reproduced from O'Sullivan et al44 with permission. Mk, megakaryocyte; XCIP, X-chromosome inactivation pattern.

Timeline of key discoveries in MPNs and single-cell methodologies. Reproduced from O'Sullivan et al44 with permission. Mk, megakaryocyte; XCIP, X-chromosome inactivation pattern.

Acknowledgment

AJM is supported by a CRUK Senior Cancer Research Fellowship (grant number C42639/A26988).

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Ashlyn Chee has no competing financial interests to declare.

Adam J. Mead has received honoraria for consulting and speaker fees from Novartis, Celgene/BMS, AbbVie, CTI, MD Education, Sierra Oncology, Medialis, MorphoSys, Ionis, Medscape, Karyopharm, Sensyn, Incyte, Galecto, Pfizer, Relay Therapeutics, GSK, Alethiomics, and Gilead; has received research funding from Celgene/BMS, Novartis, Roche, Alethiomics, and Galecto; and is cofounder and equity holder in Alethiomics Ltd, a spinout company from the University of Oxford.

Off-label drug use

Ashlyn Chee: nothing to disclose.

Adam J. Mead: nothing to disclose.