Abstract

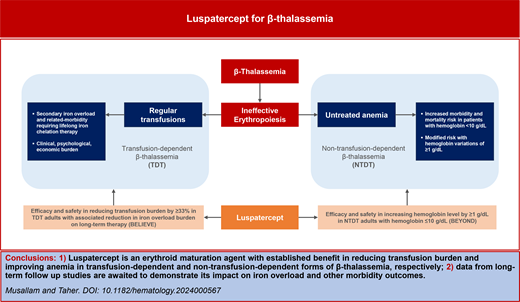

Patients with β-thalassemia continue to have several unmet needs. In non–transfusion-dependent patients, untreated ineffective erythropoiesis and anemia have been associated with a variety of clinical sequelae, with no treatment currently available beyond supportive transfusions. In transfusion-dependent forms, lifelong transfusion and iron chelation therapy are associated with considerable clinical, psychological, and economic burden on the patient and health care system. Luspatercept is a novel disease-modifying agent targeting ineffective erythropoiesis that became recently available for patients with β-thalassemia. Data from randomized clinical trials confirmed its efficacy and safety in reducing transfusion burden in transfusion-dependent patients and increasing total hemoglobin level in non–transfusion-dependent patients. Secondary clinical benefits in patient-reported outcomes and iron overload were also observed on long-term therapy, and further data from real-world evidence studies are awaited.

Learning Objectives

Identify persisting unmet needs in patients with NTDT and TDT

Evaluate the evidence base for luspatercept as a novel disease-modifying agent targeting ineffective erythropoiesis in β-thalassemia

Recognize the principles of practical application of luspatercept in the real-world setting and emerging data gaps

CLINICAL CASE

Maria is a 32-year-old woman who works as a kindergarten teacher. She was diagnosed with β-thalassemia major at the age of 8 months (β0/β+ genotype) and has received monthly red blood cell transfusions since diagnosis. She also underwent splenectomy during childhood. Her transfusion requirements have increased over time, and she currently receives 3 blood units every 4 weeks. Her pretransfusion hemoglobin level is maintained at around 9.0 g/dL. She often misses work to attend transfusion sessions as her center cannot offer transfusions over the weekend. Her latest serum ferritin level was elevated at 2800 ng/mL, while she is maintained on deferasirox film-coated tablets at a dose of 21 mg/kg/d with adherence in the range of 80% to 90%. Attempts to increase her doses were associated with gastrointestinal side effects. She was offered luspatercept treatment to reduce transfusion burden and ongoing iron intake, with the aim of improving the time lost to transfusion visits, and support iron chelation to reduce her iron levels. Luspatercept treatment was initiated at the recommended starting dose of 1 mg/kg every 3 weeks by subcutaneous injection. Since she did not show a transfusion burden reduction after 2 doses, her dose was increased to 1.25 mg/kg. Following 3 doses at 1.25 mg/kg, her transfusion burden started lessening and treatment was continued. After 6 months of treatment, her transfusion burden decreased from 3 units every 4 weeks to 3 units every 6 weeks while maintaining a pretransfusion hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL. This also allowed transfusions and luspatercept to be administered at the same hospital visit. She reported improved general energy despite the reduced transfusion regimen. On long-term follow-up, her iron parameters gradually started to improve at the same iron chelation dose. She initially suffered from arthralgia when she began luspatercept treatment. This remained at grade 1 in severity, which was easily managed by over-the-counter analgesics and resolved following 6 weeks of treatment. As such, no modifications to her treatment were required.

Introduction

β-Thalassemia is an inherited disorder of hemoglobin synthesis characterized by ineffective erythropoiesis and chronic anemia.1 Although the disease is most common in the area extending from the Mediterranean basin and Middle East toward Southeast Asia, increasing prevalence has also been observed in large multiethnic cities in the United States and Europe due to immigration.2 Patients who inherit homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the HBB gene can have a wide spectrum of phenotype severity but are usually categorized based on transfusion requirement as having non–transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (NTDT) or transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia (TDT).3 Despite the availability of supportive therapies, the chronicity of the disease continues to be associated with considerable clinical, psychological, and economic burden on the patient and health care system.4,5 Curative therapies such as bone marrow transplantation and newer gene insertion and editing techniques are also now available, but these can be limited by donor requirements, high cost, or poor access to expert centers that can perform the procedures, especially in resource-limited countries.6 Data on agents targeting ineffective erythropoiesis are limited to small clinical trials or case series, with no drugs officially approved for this indication. Luspatercept is the first disease-modifying therapy recently approved for patients with β-thalassemia. We herein provide a concise overview of luspatercept's development program in the context of persistent unmet needs for patients with TDT and NTDT while also providing guidance on its clinical application.

Pathogenesis and unmet needs in β-thalassemia

Patients are recognized as having NTDT following diagnosis in early childhood when they present with mild to moderate anemia that does not “stimulate” clinicians to introduce regular transfusion therapy.7 However, clinical observation of these patients as they grow into adulthood has demonstrated the detrimental effects of untreated ineffective erythropoiesis, which can lead to a variety of serious clinical morbidities through multiple pathways: medullary expansion, leading to bone disease; extramedullary hematopoiesis, leading to hepatosplenomegaly and pseudotumors that can cause compression of vital structures; chronic anemia and hypoxia, leading to organ failure; increased intestinal iron absorption, leading to iron-related hepatic and endocrine disease; and hemolysis, leading to a hypercoagulable state and vascular events.5,8,9 Combined, these complications can take a toll on the patient and lead to diminished quality of life and mental health.10 Iron chelation therapy has become the standard of care for NTDT patients with evidence of iron overload,5,11 but until recently, there have been no effective therapies approved for the treatment of ineffective erythropoiesis and anemia in these patients. Accordingly, we were left with no choice but to introduce regular transfusions to some of these patients to support anemia and its related symptoms, to promote growth during childhood, or to prevent/manage specific clinical complications during adulthood.5,8 Although patients transitioned to such transfusion programs have lower morbidity rates and improved survival,12,13 the wide application of transfusion therapy to the entire NTDT population is neither practical nor risk-free in view of the long-term sequelae of secondary iron overload and the need for chronic iron chelation therapy. Data from several observational studies have confirmed that NTDT patients who have hemoglobin levels of less than 10 g/dL are at higher risk of morbidity and mortality (target population for novel therapies) while increases of 1 g/dL and higher can considerably reduce these risks (target end point).14-16

In patients with TDT, clinical outcomes are tied to the adequacy of conventional treatment.17 Patients who are suboptimally transfused can suffer complications similar to those observed in patients with NTDT, and pretransfusion hemoglobin levels are directly associated with patient survival (values ≥9.5 g/dL being most favorable).18 Transfusion therapy, however, does not come without its own side effect. Similar to the case of Maria, regular transfusions and associated hospital visits are inconvenient and can lead to considerable impact on patients' social integration and work/education patterns. Secondary iron overload is also inevitable and can lead to end-organ damage in the heart, liver, and endocrine glands.4 Adequate iron chelation therapy is thus vital to ensure morbidity- and mortality-free survival, but optimal application is limited by adherence challenges as well as high health care resource utilization and the burden of chronic treatment.19-21 The target for the clinical development of novel therapies in TDT is therefore to reduce the transfusion requirement and/or improve pretransfusion hemoglobin levels in those suboptimally transfused.

Luspatercept development and clinical trials

Luspatercept is a recombinant fusion protein comprising a modified extracellular domain of the human activin receptor type IIB fused to the Fc domain of human immunoglobulin G1. These in turn bind to select transforming growth factor beta superfamily ligands, block SMAD2/3 signaling, and enhance erythroid maturation during late-stage erythropoiesis.22-24

A multicenter, open-label, dose-ranging phase 2 trial of luspatercept in adults with β-thalassemia (NCT01749540) provided initial evidence of its safety and effectiveness in both NTDT (n = 33; 58% with erythroid response defined as a hemoglobin level increase ≥1.5 g/dL vs baseline) and TDT (n = 31; 81% with an erythroid response defined as transfusion burden reduction ≥20% vs baseline).25 Hematologic benefits continued to be observed in the 5-year extension phase (NCT02268409), along with notable improvements in measures of iron overload and quality of life.26 This led to 2 registration trials in adults with TDT (BELIEVE) and NTDT (BEYOND).27,28 Trials in pediatric patients (NCT04143724) and in patients with α-thalassemia (NCT05664737) are also ongoing.

The BELIEVE trial

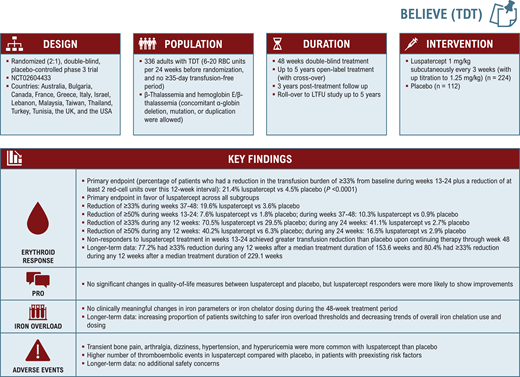

BELIEVE (NCT02604433; Figure 1) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial that included 336 adults with TDT, defined as receiving 6 to 20 packed red blood cell units in the 24 weeks prior to randomization with no transfusion-free period of 35 days or more during that time. Patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive luspatercept through subcutaneous injection (1.0 mg/kg with titration up to 1.25 mg/kg) or placebo every 3 weeks for 48 weeks or more.27 Patients who completed the double-blind period could continue or cross over to luspatercept in an open-label extension for up to 5 years or undergo posttreatment follow-up for 3 years. They were also able to join a long-term follow-up (LTFU) rollover study (NCT04064060) pooling patients from clinical trials across different indications.

During the core 48-week treatment period, a significantly greater percentage of patients receiving luspatercept achieved the primary end point of a 33% or greater reduction in transfusion burden from baseline during weeks 13 to 24 compared with placebo (21.4% vs 4.5%). The secondary endpoints of a reduction of 33% or more from weeks 37-48 and 50% or more from weeks 13 to 24 and weeks 37 to 48 also favored treatment with luspatercept over placebo.27 Continuous rolling intervals were also considered to reflect a practical clinical response time frame. A significantly greater proportion of luspatercept-treated patients achieved a reduction of 33% and higher and 50% and higher during any rolling 12-week or 24-week interval (70.5% vs 29.5% had a reduction ≥33% during any 12 weeks), respectively. Response was observed across all evaluated patient subgroups, although at different rates and magnitudes.27 Luspatercept-treated patients continued to experience reductions in transfusion burden with longer time on treatment in the open-label extension (77.2% experienced a reduction ≥33% during any 12 weeks after a median treatment duration of 153.6 weeks) and LTFU study (80.4% had a reduction ≥33% during any 12 weeks after a median treatment duration of 229.1 weeks).29,30 Adverse events consisting of transient bone pain (19.7 vs 8.3), arthralgia (19.3 vs 11.9), dizziness (11.2 vs 4.6), hypertension (8.1 vs 2.8), and hyperuricemia (7.2 vs 0) were more common with luspatercept than with placebo in the core treatment period. A higher number of thromboembolic events were observed in the luspatercept compared to the placebo arm (8 vs 1 patient), but these mostly occurred in patients with preexisting risk factors.27 No new safety concerns emerged during longer-term follow up.29,31

Overall, there were no significant changes in quality-of-life measures between luspatercept and placebo, but luspatercept responders were more likely to show improvements. Such benefit was hard to assess and interpret to begin with since the convenience of reducing hospital visits for transfusion therapy was counterbalanced by the need to come in for clinical trial assessments.32 Initial data showed modest improvement in serum ferritin level and no benefit (even slight increase) in liver iron concentration.27 This may have been due to the fact that other than decreasing iron intake due to transfusion reduction, luspatercept also stimulates erythropoiesis, which can increase iron utilization and redistribute body iron, leading to higher liver iron concentration.33 Nonetheless, long-term luspatercept treatment led to an increasing proportion of patients switching to safer iron overload thresholds and decreasing trends of overall iron chelation use and dosing.29,34,35

The BEYOND trial

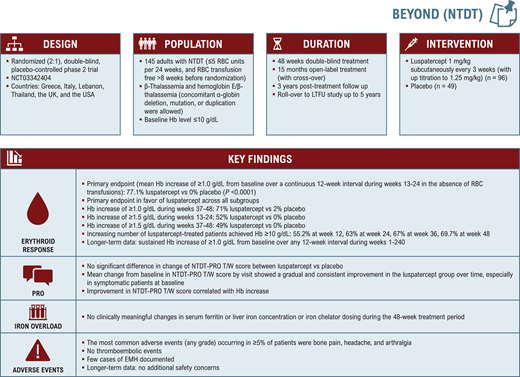

BEYOND (NCT03342404; Figure 2) was a randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of luspatercept in 145 adults with NTDT and a baseline hemoglobin level of 10 g/dL or lower.28 Patients were randomized 2:1 to receive luspatercept (1.0 mg/kg with titration up to 1.25 mg/kg) or placebo every 3 weeks for 48 weeks or longer. Patients who completed the double-blind period could continue or cross over to luspatercept in an open-label extension for up to 15 months or undergo posttreatment follow up for 3 years. They were also able to join the LTFU rollover study.

The trial met its primary endpoint of an increase from a baseline of 1.0 g/dL or higher in mean hemoglobin level over a continuous 12-week interval during weeks 13 to 24 in the absence of transfusions, observed in 77.1% of patients in the luspatercept arm (52.1% ≥ 1.5 g/dL) vs 0% in the placebo arm. Response was observed across all evaluated subgroups by age, gender, region, baseline hemoglobin level, and genotype.28 Increasing proportions of patients treated with luspatercept achieved a hemoglobin level greater than 10.0 g/dL over the 48-week period.36 Clinically meaningful and durable responses were maintained with long-term treatment for a median duration of 202.8 weeks.37

The key secondary endpoint was a change in a patient- reported outcome measure of tiredness/weakness specifically developed and validated for patients with NTDT (NTDT-PRO T/W).38 Improvement in NTDT-PRO T/W during weeks 13 to 24 favored luspatercept over placebo, although the difference was not statistically significant.28 However, the difference was more pronounced at later time points and in patients who were symptomatic at baseline, and improvement correlated with hemoglobin response.28,39 Iron overload measures remained largely unchanged. Treatment-emergent adverse events were similar to those observed in the BELIEVE trial, with a noted absence of thromboembolic events.28 Extramedullary hematopoiesis was reported in 6 patients (6%) in the luspatercept group and in 1 patient (2%) in the placebo group.28 Whether this reflected a causal relationship with treatment vs natural disease progression was not fully determined. Data from real-world case reports of luspatercept in TDT are conflicting, with some observing the emergence of extramedullary hematopoiesis masses following luspatercept initiation and others reporting safe use or suggesting resolution in patients with existing masses.40

Place in therapy and practical application

Transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia

Based on data from the BELIEVE trial, luspatercept was approved in the United States (2019) and Europe (2020) for the treatment of anemia in adult patients with TDT. It is also now recommended by international management guidelines for any TDT patient aged 18 years or older.4 Despite the broad indication, the limited real-life experience combined with affordability issues in resource-limited settings may require clinicians to adopt some level of patient prioritization, and guidance toward this end has been recently published based on expert opinion.41 For instance, based on data from the BELIEVE trial and more recent real-world evidence from Greece, patients who have a non-β0/β0 genotype, who are splenectomized, and who have a low to moderate transfusion burden may show an earlier response, a higher magnitude of response, or require lower doses and could be prioritized.27,41-44 This is exemplified by the described case of Maria.

Dosing and adverse event monitoring recommendations for luspatercept use in TDT patients are summarized in Table 1. Defining responses to luspatercept therapy and relevant decisions on treatment continuation may not be straightforward.41 According to the product label, response (defined as a reduction ≥33% in transfusion burden in the European Medicines Agency label and as any reduction in the US Food and Drug Administration label) should be evaluated after 2 or more doses for potential dose escalation, while treatment discontinuation is recommended if no reduction in transfusion burden is noted following 3 doses at the maximum dose (15 weeks from initiation of therapy).45,46 However, a delayed response has been documented through various analyses of the BELIEVE trial, raising the question of whether we are recommending treatment discontinuation a bit “too soon.”27,47 In resource-limited countries with inadequate access and suboptimal transfusion practices, defining response as “transfusion reduction” in itself may become a challenge since improvements in pretransfusion hemoglobin levels at the same transfusion regimen may be regarded as a clinical benefit.41

Non–transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia

The application for regulatory approval in the United States for luspatercept as a treatment of anemia in NTDT was withdrawn in June 2022 for lack of agreement on the benefits and risks. However, luspatercept received approval in Europe in March 2023 as a treatment for adult patients with anemia associated with NTDT. It is now also indicated for adults with NTDT in international management guidelines and expert recommendations, especially for patients with a hemoglobin level lower than 10 g/dL and/or anemia-related symptoms, to achieve hemoglobin increases of 1 g/dL or higher.5,8 This would represent the first disease-modifying therapy becoming available for NTDT. The need for intervention is clinically plausible for patients with anemia-related symptoms, and although luspatercept's patient- reported outcomes were not as anticipated in the overall BEYOND population, beneficial effects were clear in patients who had symptoms at baseline. Introducing luspatercept for patients with a hemoglobin level of less than 10 g/dL and no symptoms may be met with some skepticism, but it is essential to understand that this is aimed at “preventing” secondary pathophysiology (eg, iron overload and hypercoagulability) and future clinical morbidities linked to the chronic state of untreated ineffective erythropoiesis and anemia. Although mechanistic effects have been demonstrated in the BEYOND trial with improvement in markers of ineffective erythropoiesis, reduced extramedullary hematopoiesis, and improved iron homeostasis48; data on long-term impacts on morbidity development are still awaited.

Conclusion and future directions

Luspatercept is the newest option available for the treatment of patients with β-thalassemia. Practical experience with its use in TDT patients is growing, while additional data from real-world studies are awaited to further define its clinical benefit from a patient and physician perspective. Identifying new clinical and biochemical markers that can predict early and late response is also essential to strategize treatment. In patients with NTDT, long-term data are valuable to understand benefit in terms of iron overload and morbidity prevention. Extending the indication to pediatric patients (TDT and NTDT) maximizes value by targeting ineffective erythropoiesis before sequelae start to manifest. Revisiting the position of luspatercept as a treatment option for β-thalassemia is needed once additional disease-modifying agents become available. The oral pyruvate kinase activator mitapivat is currently the most advanced in clinical development, and data from NTDT and TDT patient cohorts will shortly become available from phase 3 clinical trials.49

Conflict-of-interest disclosure

Khaled M. Musallam: consultancy: Novartis, Celgene Corp (Bristol Myers Squibb), Agios Pharmaceuticals, CRISPR Therapeutics, Vifor Pharma, Pharmacosmos; research funding: Agios Pharmaceuticals, Pharmacosmos.

Ali T. Taher: consultancy: Novo Nordisk, Celgene Corp (Bristol Myers Squibb), Agios Pharmaceuticals, Vifor Pharma, Pharmacosmos; research funding: Celgene Corp (Bristol Myers Squibb), Agios Pharmaceuticals, Vifor Pharma, Pharmacosmos.

Off-label drug use

Khaled M. Musallam: Luspatercept is not approved for use in non-transfusion-dependent β-thalassemia in the United States.

Ali T. Taher: Luspatercept is not approved for use in non-transfusion- dependent β-thalassemia in the United States.