Key Points

Using a physiological-based approach, we find a ferritin threshold of 33 μg/L in both men and postmenopausal women, and 25 μg/L for premenopausal non-pregnant women for ID.

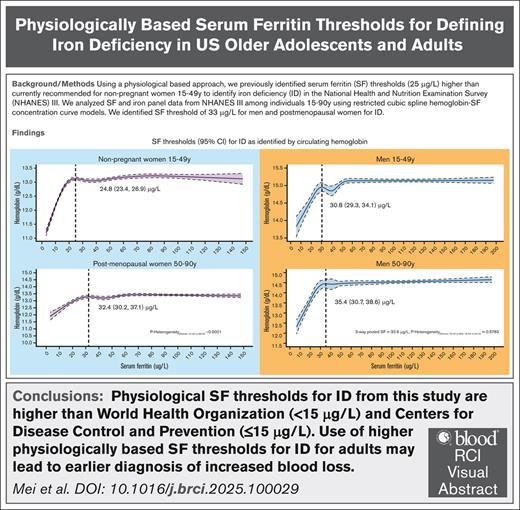

Visual Abstract

World Health Organization (WHO) and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines recommend a serum ferritin (SF) threshold for iron deficiency (ID) of <15 μg/L and ≤15 μg/L, respectively, for healthy adults aged 15 to >60 years. In apparently healthy adults, we used SF at which the circulating hemoglobin (Hb) begins to decrease and the erythrocyte zinc protoporphyrin begins to increase as a potential physiological indicator of the ID threshold. We analyzed data for 5169 men and 6957 nonpregnant women, aged 15 to 90 years, from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (1988-1994). Physiologically based SF thresholds for ID were higher than WHO and CDC recommendations (P < .001 for all). For men and postmenopausal women, SF thresholds corresponding to the initial decline in circulating Hb did not differ significantly, with an overall threshold of 32.6 μg/L (95% confidence interval [CI], 27.4-37.7). The SF threshold for premenopausal women was 24.8 μg/L (95% CI, 23.4-26.9), lower than that for men and postmenopausal women (P < .0001). The difference between SF physiologically based thresholds in men and older women, with basal iron losses, compared with younger women, with menstrual/basal iron losses, provides evidence that hepcidin regulation of iron homeostasis controls the onset for ID in healthy adults. Clinically, use of higher physiologically based SF thresholds for ID for adults may lead to earlier diagnosis of increased blood loss.

Introduction

In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) published updated guidelines for the use of serum ferritin (SF) concentrations to assess iron status in apparently healthy individuals and populations, formulated in accordance with the WHO evidence-informed guideline-development procedures and relying on comprehensive systematic reviews.1 Iron deficiency (ID) was considered to be present “when body iron stores are inadequate to meet the needs for metabolism. Progressive iron deficiency can result in iron-deficient erythropoiesis (formation of red blood cells) and, eventually, iron deficiency anaemia.”1 Serum (or plasma) ferritin concentration was determined to be a good marker of iron stores that should be used to diagnose ID in otherwise apparently healthy individuals. For the guidelines, ID was defined as absent iron stores in the bone marrow.1 Noting that available studies were not sufficient to justify a change in current guidance, a single threshold cutoff value of <15 μg/L was recommended for ID in otherwise apparently healthy adults, aged ≥20 years, with a low to very low certainty of evidence.1,2 The single threshold for ID in adults originated in expert opinion that was last revised in 1993 and remained unchanged during technical meetings for WHO guideline development between 2010 and 2016.1,3 In otherwise apparently healthy indiviuals with iron deficiency, the relationship between SF and bone marrow iron stores has been examined in a total of 51 younger men4,5 and no data have been reported for postmenopausal women or older men.

In 1998, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released the current recommendations to prevent and control ID in the United States, using SF of ≤15 μg/L as the threshold for defining ID in all individuals aged >6 months,6 citing a single study of 203 adult nonpregnant women.7

In healthy adults, an alternative to the use of absent iron stores in the bone marrow to define ID may be considered. To determine whether body iron stores are inadequate to meet the needs for metabolism (erythropoiesis and tissue requirements) in the absence of inflammation, another approach is to use physiological indicators of ID in high-quality laboratory data from cross-sectional population studies. With this approach, after excluding participants with evidence of inflammation or infection, the SF concentration is used as a measure of body iron stores in each individual. Concurrence between a decrease in the circulating hemoglobin (Hb) concentration and an independently measured indicator of increased iron requirements identifies an SF threshold and provides evidence that ID is responsible for reduced Hb synthesis rather than other causes of impaired erythropoiesis. In previous studies of children, pregnant women, and nonpregnant women of reproductive age, we have used either soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) or erythrocyte zinc protoporphyrin (eZnPP) as the independently measured indicators of increased iron requirements.8-11 In the absence of erythroid hyperplasia, plasma sTfR concentrations reflect cellular iron requirements and provide a sensitive, quantitative measure of iron-deficient erythropoiesis.12-14 In the developing erythroblast, eZnPP provides a measure of an inadequate iron supply that persists as an index of increased iron need for the life of the circulating erythrocyte.14

In this study, we used the circulating Hb concentration and eZnPP as physiological indicators of the threshold for the presence of ID in the analysis of data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III, 1988-1994),15,16 the last NHANES with multiple iron biomarkers from men and postmenopausal women. We compared these SF thresholds for men and postmenopausal women with our earlier results using identical methods from the same NHANES III survey for premenopausal women.10 The median age of natural menopause is 51 years (range, 45-56) in the United States.15,16 We used age to indicate menstrual status. Although recent data from NHANES 2017 to March 2020 for men and postmenopausal women do not include sTfR or eZnPP to indicate concurrent increased iron needs, we also compared the SF thresholds corresponding to the initial decline in circulating Hb with those from NHANES 1988-1994. We hypothesized that separate and distinct physiological SF thresholds would be needed for men and postmenopausal women, with basal iron losses, compared with premenopausal women, with menstrual and basal iron losses.

Methods

Study population and sample selection

Data from NHANES III, 1988 to 1994, represent the civilian noninstitutionalized population in the United States in that period. NHANES is a multipurpose survey designed to assess the health and nutritional status of adults and children in the United States that includes an interview in the household followed by a standardized health examination in a mobile examination center (MEC).15,16 NHANES III relied on a stratified multistage probability sample based on the selection of counties, blocks, households, and people within households. The surveys were conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics at the CDC. Ethical approval was obtained, and written informed consent was obtained from participants aged ≥12 years. Parental consent was obtained for those aged <18 years. Procedures for data collection and analysis have been published elsewhere.15,16

NHANES III measured SF, Hb, and eZnPP.15,16 For this analysis, we restricted our study sample to 8889 men and 10 115 nonpregnant women aged 15 to 90 years who received health examinations in a MEC. Data for nonpregnant women aged 15 to 49 years were published in a previous study,10 and we reanalyzed these data for inclusion in this analysis to compare with nonpregnant women aged 50 to 90 years. We excluded participants who had missing measurements on SF, eZnPP, Hb, C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell counts, alanine amino transferase (ALT), or aspartate amino transferase (AST). We then identified an apparently healthy subsample by using NHANES III data to exclude participants with other common causes of anemia at the population level that are independent of ID, namely those with an indicator of infection (white blood cell count of >10.0 × 109/L) or inflammation (CRP of >5.0 mg/L17), or potential liver disease (as defined by elevations of ALT at >70 U/L or AST at >70 U/L).18 In addition, we excluded participants at risk of iron overload (current WHO cutoff for severe risk of iron overload is SF of >200 μg/L for males, and SF of >150 μg/L for females aged ≥5 years).1 Our final sample included 5169 men and 6957 nonpregnant women aged 15 to 90 years, and this represents 58.2% of men, and 68.8% of women, of the originally examined sample. Detailed sample selection is presented in Figure 1.

Flowchart for final apparently healthy sample selection of US men and nonpregnant women aged 15 to 90 years participating in NHANES III, 1988-1994.

Flowchart for final apparently healthy sample selection of US men and nonpregnant women aged 15 to 90 years participating in NHANES III, 1988-1994.

Laboratory analysis

NHANES III measured SF, eZnPP, Hb, CRP, ALT, AST, and white blood cell count for both men and women aged 15 to 90 years.15,16 Both SF and eZnPP were measured in the NHANES Laboratory, National Center for Environmental Health, at the CDC.

SF was measured using the Bio-Rad Laboratories QuantImune Ferritin IRMA kit,19 which is a single-incubation 2-site immunoradiometric assay (IRMA). In this IRMA, which measured the most basic isoferritins, the highly purified 125I-labeled antibody to ferritin was the tracer, and the ferritin antibodies were immobilized on polyacrylamide beads as the solid phase.16

eZnPP was measured by a modification of the method of Sassa et al20 using a Hitachi model F-2000 fluorescence spectrophotometer.16 Protoporphyrin was extracted from EDTA–whole blood into a 2:1 (volume/volume) mixture of ethyl acetate–acetic acid, then backextracted into diluted hydrochloric acid. The protoporphyrin in the aqueous phase was measured fluorometrically at excitation and emission wavelengths of 404 and 655 nm, respectively. Calculations were based on a processed protoporphyrin IX (free acid) standard curve. After a correction for the individual hematocrit was made, the final concentration of eZnPP in a specimen was expressed as micrograms per deciliter of packed red blood cells.16

Hb was part of the hematology parameters in whole blood that were measured as part of a complete blood count in the MEC using the Coulter Counter Model S-PLUS JR with Coulter histogram differential, hereafter referred to as the Model S-PLUS JR, a quantitative, automated hematology analyzer.16 Complete blood counts, including white blood cell counts, were also measured in the MEC using the Coulter Counter Model S-PLUS JR.16 We used the original Hb data without adjustment for altitude (data not publicly posted) or smoking status.

CRP was measured using serum at the University of Washington (Seattle, WA) by latex-enhanced nephelometry (Behring Nephelometer Analyzer System; Behring Diagnostics Inc, Somerville, NJ).16 Both ALT and AST were part of the standard biochemistry profile that was measured using serum in the White Sands Research Center (Alamogordo, NM), using a Hitachi model 737 multichannel analyzer (Boehringer Mannheim Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).16

Because NHANES III data were collected over 3 decades ago, we also analyzed the recent NHANES 2017 to March 2020 prepandemic data.21 However, NHANES 2017 to March 2020 measured only SF and Hb for men and women aged 15 to 90 years and did not measure eZnPP, although sTfR was measured for women aged 15 to 49 years. Detailed sample selection and laboratory measurements are presented in the supplemental Methods.

Statistical analysis

First, we log-transformed SF [log10(ferritin)] data to normalize the distributions, because previous studies suggested that the SF distribution is a typically right-skewed distribution1; then calculated geometric means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and described the SF distributions with basic characteristics for men aged 15 to 90 years and nonpregnant women aged 50 to 90 years. For basic characteristics and SF distribution analysis, we used SUDAAN (version 11.0.1; Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) with examination sample weights and design variables to account for the complex sample design. A Bonferroni adjustment22 was used to correct the P values for the significance test for the multiple comparisons across each sociodemographic characteristic in SF.

Using exploratory data analysis techniques,23 we examined monotonic relationships between Hb and SF, and between eZnPP and SF, using a scattergram superimposed with a plot of concentrations of median Hb and median eZnPP according to categories of SF levels for men and nonpregnant women (10 μg/L). Restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression models with 5 knots24 were used to examine the relationship of (1) continuous SF with Hb, and (2) continuous SF with eZnPP for both men and nonpregnant women aged 15 to 90 years, to identify the potential SF thresholds for ID. We used 2 complementary analyses to achieve our objectives. First, with Hb as our outcome variable, we modeled its relationship with SF and then solved the SF concentration corresponding to the Hb plateau. Second, to further ascertain the consistency of this derived SF threshold, we modeled SF against eZnPP and solved for the SF value corresponding to the eZnPP minima. Using the fitted function of these 2 separate RCSs, we solved the ordinary differential equation derivative solutions at the plateau or minimum of each model, with both in SF units. The above RCS analysis methods were also repeated after stratification of the NHANES III data by age groups to examine variation in age groups.

For the RCS analysis, R software 4.4.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing and Graphics, Vienna, Austria) was used without accounting for the complex sample design because we did not intend to generate nationally representative results using the RCS analysis, but rather to understand the biologic relationships within the sampled apparently healthy individuals with respect to these iron status indicators. Bootstrap resampling techniques were used to generate the 95% CIs around each plateau or minimum point estimate derived from the differential solution of each RCS fit. For each model, 5000 replications were generated, and the 95% CI estimates were corrected for bias using bias corrected acceleration.25 The Cochrane Q test for 3-way heterogeneity in the calculated SF thresholds were performed using 2-sided random effect meta-analysis.26 Statistical significance was set at a priori and 2-tailed P < .05 for all analyses.

eZnPP is an indicator of ID but also used to measure blood lead levels (BLL). We conducted sensitivity analyses excluding those with elevated BLL of >5.0 μg/dL and repeated the analyses to examine the physiological thresholds between SF and eZnpp.

We repeated the aforementioned analysis using NHANES 2017 to March 2020 to examine the physiological thresholds between SF and Hb for both men and nonpregnant women aged 15 to 90 years. Additionally, using the full NHANES III SF and Hb data (no exclusions to create the healthy populations), we compared the prevalence of ID and ID anemia (IDA) using thresholds of the current WHO, current CDC, and the new physiologically based thresholds.

Results

Geometric mean SF concentrations were 87.3 μg/L (95% CI, 85.0-89.6) for men aged 15 to 90 years (Table 1). There was no statistical difference of geometric mean SF concentrations between men aged 15 to 49 years and those aged 50 to 90 years. However, the geometric mean SF concentrations in non-Hispanic White men were significantly higher (P < .05) than in Mexican American men (Table 1). Geometric mean SF concentrations were 56.9 μg/L (95% CI, 54.5-59.4) for nonpregnant women aged 50 to 90 years (P < .05), and the geometric mean SF concentrations in non-Hispanic White women were statistically significantly higher (P < .05) than non-Hispanic Black and Mexican American women (Table 1).

SF concentrations in a healthy population of US men and nonpregnant women aged 15 to 90 years participating in NHANES III (1988-1994)

| . | N . | Geometric mean∗ (95% CI) . | Median (95% CI) . | 5th percentile (95% CI) . | 95th percentile (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||||

| Total | 5169 | 87.3 (85.0-89.6) | 99.6 (97.2-103.3) | 23.3 (21.5-26.8) | 185.4 (183.7-188.9) |

| Age, y | |||||

| 15-49 | 3285 | 87.3 (84.9-89.7)a | 99.1 (96.3-102.8) | 23.6 (20.7-27.9) | 184.4 (181.6-187.6) |

| 50-90 | 1884 | 87.2 (82.1-92.6)a | 101.5 (96.2-108.8) | 21.5 (17.8-27.4) | 189.0 (184.6-193.2) |

| Race/ethnic group | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2038 | 88.1 (85.3-90.9)a | 100.5 (97.3-105.7) | 24.0 (21.2-27.6) | 185.2 (183.3-189.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1319 | 86.3 (83.1-89.5)a,b | 97.2 (94.1-102.4) | 24.2 (22.1-27.8) | 185.4 (182.0-191.4) |

| Mexican American | 1621 | 80.7 (75.9-85.8)b,c | 89.9 (84.5-96.6) | 22.3 (19.2-28.1) | 184.0 (179.7-188.7) |

| All others | 191 | 86.3 (76.3-97.5)a,c | 100.7 (88.8-116.2) | 20.3 (16.1-31.5) | 186.3 (174.4 to –) |

| Nonpregnant women | |||||

| Total (15-90 y) | 6957 | 36.3 (34.9-37.9) | 40.0 (38.6-43.1) | 6.4 (5.9-7.4) | 119.8 (116.7-123.2) |

| Age, y | |||||

| 15-49† | 4639 | 30.2 (28.8-31.8)a | 32.9 (31.3-35.5) | 5.5 (5.1-6.8) | 103.0 (98.2-108.4) |

| 50-90 | 2318 | 56.9 (54.5-59.4)b | 64.5 (61.6-69.3) | 14.1 (13.1-16.1) | 136.2 (131.5-141.4) |

| Race/ethnic group‡ | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2831 | 38.6 (36.7-40.6)a | 42.5 (40.6-46.1) | 7.7 (7.0-9.4) | 120.2 (116.2-125.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1982 | 34.5 (32.8-36.2)b | 38.3 (36.3-41.6) | 5.4 (4.8-6.7) | 128.0 (122.6-133.9) |

| Mexican American | 1824 | 27.0 (25.6-28.4)c | 28.3 (26.6-31.1) | 2.8 (2.6-3.5) | 110.5 (106.7-113.4) |

| All others | 313 | 26.3 (21.8-31.8)b,c | 27.5 (22.6-35.5) | 4.9 (– to 6.0) | 110.5 (93.1-116.8) |

| . | N . | Geometric mean∗ (95% CI) . | Median (95% CI) . | 5th percentile (95% CI) . | 95th percentile (95% CI) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||||

| Total | 5169 | 87.3 (85.0-89.6) | 99.6 (97.2-103.3) | 23.3 (21.5-26.8) | 185.4 (183.7-188.9) |

| Age, y | |||||

| 15-49 | 3285 | 87.3 (84.9-89.7)a | 99.1 (96.3-102.8) | 23.6 (20.7-27.9) | 184.4 (181.6-187.6) |

| 50-90 | 1884 | 87.2 (82.1-92.6)a | 101.5 (96.2-108.8) | 21.5 (17.8-27.4) | 189.0 (184.6-193.2) |

| Race/ethnic group | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2038 | 88.1 (85.3-90.9)a | 100.5 (97.3-105.7) | 24.0 (21.2-27.6) | 185.2 (183.3-189.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1319 | 86.3 (83.1-89.5)a,b | 97.2 (94.1-102.4) | 24.2 (22.1-27.8) | 185.4 (182.0-191.4) |

| Mexican American | 1621 | 80.7 (75.9-85.8)b,c | 89.9 (84.5-96.6) | 22.3 (19.2-28.1) | 184.0 (179.7-188.7) |

| All others | 191 | 86.3 (76.3-97.5)a,c | 100.7 (88.8-116.2) | 20.3 (16.1-31.5) | 186.3 (174.4 to –) |

| Nonpregnant women | |||||

| Total (15-90 y) | 6957 | 36.3 (34.9-37.9) | 40.0 (38.6-43.1) | 6.4 (5.9-7.4) | 119.8 (116.7-123.2) |

| Age, y | |||||

| 15-49† | 4639 | 30.2 (28.8-31.8)a | 32.9 (31.3-35.5) | 5.5 (5.1-6.8) | 103.0 (98.2-108.4) |

| 50-90 | 2318 | 56.9 (54.5-59.4)b | 64.5 (61.6-69.3) | 14.1 (13.1-16.1) | 136.2 (131.5-141.4) |

| Race/ethnic group‡ | |||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 2831 | 38.6 (36.7-40.6)a | 42.5 (40.6-46.1) | 7.7 (7.0-9.4) | 120.2 (116.2-125.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1982 | 34.5 (32.8-36.2)b | 38.3 (36.3-41.6) | 5.4 (4.8-6.7) | 128.0 (122.6-133.9) |

| Mexican American | 1824 | 27.0 (25.6-28.4)c | 28.3 (26.6-31.1) | 2.8 (2.6-3.5) | 110.5 (106.7-113.4) |

| All others | 313 | 26.3 (21.8-31.8)b,c | 27.5 (22.6-35.5) | 4.9 (– to 6.0) | 110.5 (93.1-116.8) |

SF concentrations (μg/L) in a healthy population, with unweighted n; all other analyses are weighted. – indicates that the percentile value cannot be calculated. The following exclusions apply to define a healthy sample: men or nonpregnant women with infection (white blood cell counts of >10.0 × 109/L, all ages), inflammation (CRP of >5.0 mg/L), potential liver disease (ALT of >70 U/L or AST of >70 U/L), and risk for iron overload (ferritin of >150 μg/L for females and >200 μg/L for males).

Within a group, values with different superscript letters (a, b, or c) are significantly different, P < .05 (2-tailed pairwise t test) and a Bonferroni adjustment was used to correct the P values for the significance test for the multiple comparisons across each sociodemographic characteristic in SF.

The results for nonpregnant women aged 15 to 49 years were published in a previous study.10

Race/ethnicity variable was missing for 7 women.

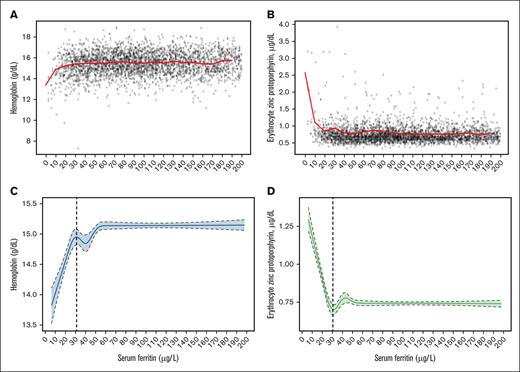

The median Hb to SF (Figures 2A and 3A), and eZnPP to SF (Figures 2B and 3B) plots are shown in Figure 2 for men aged 15 to 49 years and in Figure 3 for men aged 50 to 90 years. These empirical distribution plots indicated clear nonlinear trends with distinct thresholds conspicuous at certain levels of SF (x-axis), and inflection points at levels of Hb or eZnPP (y-axis). The RCS regression curves for both median Hb (Figures 2C and 3C) and median eZnPP (Figures 2D and 3D) are presented in Figures 2 and 3 for men aged 15 to 49 years and 50 to 90 years, respectively. Using RCS regression analysis, we found curvilinear relationships between SF and median Hb, and between SF and median eZnPP, for men. The SF values corresponding to both the Hb plateau point and the eZnPP minimum point for men aged 15 to 90 years were 32.4 μg/L and 31.0 μg/L, respectively, and did not differ significantly (Table 2). When stratified by age, the corresponding plateau points for older men (aged 50-90 years) were not significantly different than those for younger men (aged 15-49 years) for median Hb or for the median eZnPP minimum point (Table 2).

Data plot and RCS regression for men aged 15 to 49 years. The plots show SF concentrations with median Hb (A; red line) and median eZnPP (B; red line), as well as RCS regressions with 5 knots for Hb (C; the vertical dashed line indicates the plateau point) and eZnPP (D; the vertical dashed line indicates the minimum point), in a healthy sample of US men aged 15 to 49 years (n = 3285) participating in NHANES III, 1988 to 1994. Shaded areas between the dashed lines represent 95% CIs.

Data plot and RCS regression for men aged 15 to 49 years. The plots show SF concentrations with median Hb (A; red line) and median eZnPP (B; red line), as well as RCS regressions with 5 knots for Hb (C; the vertical dashed line indicates the plateau point) and eZnPP (D; the vertical dashed line indicates the minimum point), in a healthy sample of US men aged 15 to 49 years (n = 3285) participating in NHANES III, 1988 to 1994. Shaded areas between the dashed lines represent 95% CIs.

Data plot and RCS regression for men aged 50 to 90 years. The plots show SF concentrations with median Hb (A; red line) and median eZnPP (B; red line), as well as RCS regressions with 5 knots for Hb (C; the vertical dashed line indicates the plateau point) and eZnPP (D; the vertical dashed line indicates the minimum point), in a healthy sample of US men aged 50 to 90 years (n = 1884) participating in NHANES III, 1988 to 1994. Shaded areas between the dashed lines represent 95% CIs.

Data plot and RCS regression for men aged 50 to 90 years. The plots show SF concentrations with median Hb (A; red line) and median eZnPP (B; red line), as well as RCS regressions with 5 knots for Hb (C; the vertical dashed line indicates the plateau point) and eZnPP (D; the vertical dashed line indicates the minimum point), in a healthy sample of US men aged 50 to 90 years (n = 1884) participating in NHANES III, 1988 to 1994. Shaded areas between the dashed lines represent 95% CIs.

SF concentration thresholds identified by Hb and eZnPP using RCS regression with 5 knots in a healthy sample of US men and nonpregnant women aged 15 to 90 years participating in NHANES III (1988-1994)

| . | Aged 15-90 y . | Aged 15-49 y . | Aged 50-90 y . | P value, 3-way differences (df = 2) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | n = 5169 | n = 3285 | n = 1884 | |

| Hb | ||||

| SF corresponding to Hb plateau point | 32.4 (30.6-35.7)a | 30.8 (29.3-34.1)a | 35.4 (30.7-38.6)a | .5804 |

| RCS model adjusted R2, % (95% CI) | 5.7 | 3.2 | 8.8 | |

| eZnPP | ||||

| SF corresponding to eZnPP minimum point | 31.0 (30.1-33.4)a | 31.1 (30.0-34.4)a | 30.6 (29.3-34.2)a | .9841 |

| RCS model adjusted R2, % (95% CI) | 10.2 | 5.7 | 14.3 | |

| Women | n = 6957† | n = 4639‡ | n = 2318 | |

| Hb | ||||

| SF corresponding to Hb plateau point | – | 24.8 (23.4-26.9)a | 32.4 (30.2-37.1)b | <.0001 |

| RCS model adjusted R2, % (95% CI) | – | 21.3 | 5.0 | |

| eZnPP | ||||

| SF corresponding to eZnPP minimum point | – | 22.5 (21.7-23.3)b | 30.7 (29.4-33.7)b | <.0001 |

| RCS model adjusted R2, % (95% CI) | – | 23.8 | 6.0 | |

| Men aged 15-90 y and women aged 50-90 y (meta-analysis) | Pooled effect size (3-way) | |||

| SF via Hb (95% CI) | 32.6 (27.4-37.7) | .5783 | ||

| SF via eZnPP (95% CI) | 30.8 (30.2-31.4) | .9728 | ||

| P value for SF threshold difference analyses | ||||

| SF via Hb (WRA 15-49 y vs men/non-WRA) | <.0001 | |||

| SF via eZnPP (WRA 15-4 9y vs men/non-WRA) | <.0001 |

| . | Aged 15-90 y . | Aged 15-49 y . | Aged 50-90 y . | P value, 3-way differences (df = 2) . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | n = 5169 | n = 3285 | n = 1884 | |

| Hb | ||||

| SF corresponding to Hb plateau point | 32.4 (30.6-35.7)a | 30.8 (29.3-34.1)a | 35.4 (30.7-38.6)a | .5804 |

| RCS model adjusted R2, % (95% CI) | 5.7 | 3.2 | 8.8 | |

| eZnPP | ||||

| SF corresponding to eZnPP minimum point | 31.0 (30.1-33.4)a | 31.1 (30.0-34.4)a | 30.6 (29.3-34.2)a | .9841 |

| RCS model adjusted R2, % (95% CI) | 10.2 | 5.7 | 14.3 | |

| Women | n = 6957† | n = 4639‡ | n = 2318 | |

| Hb | ||||

| SF corresponding to Hb plateau point | – | 24.8 (23.4-26.9)a | 32.4 (30.2-37.1)b | <.0001 |

| RCS model adjusted R2, % (95% CI) | – | 21.3 | 5.0 | |

| eZnPP | ||||

| SF corresponding to eZnPP minimum point | – | 22.5 (21.7-23.3)b | 30.7 (29.4-33.7)b | <.0001 |

| RCS model adjusted R2, % (95% CI) | – | 23.8 | 6.0 | |

| Men aged 15-90 y and women aged 50-90 y (meta-analysis) | Pooled effect size (3-way) | |||

| SF via Hb (95% CI) | 32.6 (27.4-37.7) | .5783 | ||

| SF via eZnPP (95% CI) | 30.8 (30.2-31.4) | .9728 | ||

| P value for SF threshold difference analyses | ||||

| SF via Hb (WRA 15-49 y vs men/non-WRA) | <.0001 | |||

| SF via eZnPP (WRA 15-4 9y vs men/non-WRA) | <.0001 |

SF concentration thresholds are given in micrograms per liter. The data represent unweighted n and analyses. The following exclusions apply to define a healthy sample: men or nonpregnant women with infection (white blood cell count of >10.0 × 109/L), inflammation (CRP of >5.0 mg/L) or possible liver disease (ALT of >70 U/L, or AST of >70 U/L), and risk for iron overload (ferritin of >150 μg/L for females and >200 μg/L for males).

df, degree of freedom; WRA, women of reproductive age.

∗All estimates of plateaus and minima and their 95% CIs were obtained from 5000 bootstrap replicates. All CIs have been corrected for bias using the bias corrected acceleration approach.24 Column values with different superscript letters (a or b) are significantly different, P < .05.

Individual participant data of combined 6957 women aged 15 to 90 years was not estimated due to observed age-stratum specific effect modification (P-heterogeneity < .0001) in derived physiologic ferritin thresholds of women aged 15 to 49 years vs ≥50 years.

The results for nonpregnant women aged 15 to 49 years were published in a previous study.10

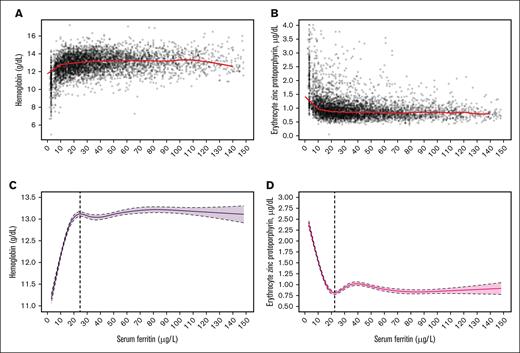

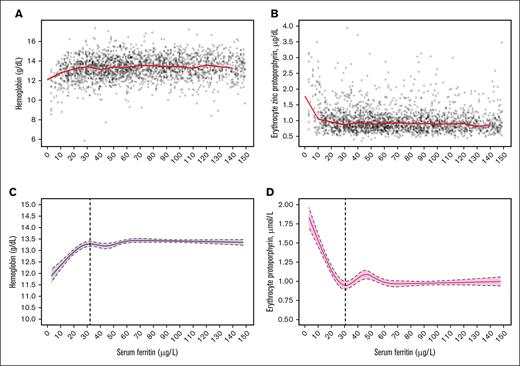

Figures 4 and 5 present the median Hb and eZnPP plots and related RCS regression curves for nonpregnant women aged 15 to 49 years (Figures 4A,C and 4B,D) and aged 50 to 90 years (Figures 5A,C and 5B,D), respectively. The SF values corresponding to both the Hb plateau point and the eZnPP minimum point were 32.4 μg/L and 30.7 μg/L for women aged 50 to 90 years, respectively, and both were significantly higher (P < .0001) than for women aged 15 to 49 years (24.8 μg/L with Hb, and 22.5 μg/L with eZnPP). In further post hoc meta-analyses, SF thresholds for postmenopausal women (aged 50-90 years) and men (aged 15-49 and 50-90 years), indicated no significant differences, with an overall threshold of 32.6 μg/L (95% CI 27.4-37.7; 3-way, P = .5783) based on Hb; and 30.8 μg/L (95% CI, 30.2-31.4; 3-way, P = .9728) with eZnPP (Table 2). In sensitivity analyses, excluding those with elevated BLL of >5.0 μg/dL, had no effect on the SF thresholds based on eZnPP (data not shown).

Data plot and RCS regression for women aged 15 to 49 years. The plots show SF concentrations with median Hb (A; red line), and median eZnPP (B; red line), as well as RCS regressions with 5 knots for Hb (C; the vertical dashed line indicates the plateau point) and eZnPP (D; the vertical dashed line indicates the minimum point), in a healthy sample of US nonpregnant women aged 15 to 49 years (n = 4639) participating in NHANES III, 1988 to 1994 (results were published in a previous study10). Shaded areas between the dashed lines represent 95% CIs.

Data plot and RCS regression for women aged 15 to 49 years. The plots show SF concentrations with median Hb (A; red line), and median eZnPP (B; red line), as well as RCS regressions with 5 knots for Hb (C; the vertical dashed line indicates the plateau point) and eZnPP (D; the vertical dashed line indicates the minimum point), in a healthy sample of US nonpregnant women aged 15 to 49 years (n = 4639) participating in NHANES III, 1988 to 1994 (results were published in a previous study10). Shaded areas between the dashed lines represent 95% CIs.

Data plot and RCS regression for women aged 50 to 90 years. The plots show SF concentrations with median Hb (A; red line, and median eZnPP (B; red line), as well as RCS regressions with 5 knots for Hb; (C; the vertical dashed line indicates the plateau point) and eZnPP (D; the vertical dashed line indicates the minimum point), for a healthy sample of US nonpregnant women aged 50 to 90 years (n = 1884) participating in NHANES III, 1988 to 1994. Shaded areas between the dashed lines represent 95% CIs.

Data plot and RCS regression for women aged 50 to 90 years. The plots show SF concentrations with median Hb (A; red line, and median eZnPP (B; red line), as well as RCS regressions with 5 knots for Hb; (C; the vertical dashed line indicates the plateau point) and eZnPP (D; the vertical dashed line indicates the minimum point), for a healthy sample of US nonpregnant women aged 50 to 90 years (n = 1884) participating in NHANES III, 1988 to 1994. Shaded areas between the dashed lines represent 95% CIs.

Table 3 compares the differences between the proportions of men and nonpregnant women classified with ID or with IDA by using thresholds of the current WHO, current CDC, and new physiologically based thresholds from this analysis and those previously published for women aged 15 to 49 years.10 In general, physiologically based thresholds identified more ID without anemia than those by the current WHO or CDC thresholds (Table 3).

Comparison of prevalence of ID and IDA defined by low SF using current WHO threshold, current CDC threshold, and the thresholds identified from this physiologically based analysis in full populations of US men and nonpregnant women aged 15 to 90 years participating in NHANES III (1988-1994)

| . | N . | Current WHO threshold . | Current CDC threshold . | Physiologically based thresholds . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % ID . | % IDA . | % ID . | % IDA . | % ID . | % IDA . | ||

| Men | |||||||

| Total | 8413 | 1.1 (0.8-1.4) | 0.4 (0.2-0.5) | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) | 6.1 (5.4-6.8) | 0.8 (0.5-1.0) |

| Aged 15-49 y | 4982 | 1.1 (0.6-1.5) | 0.2 (0.0-0.4) | 1.2 (0.7-1.7) | 0.3 (0.1-0.6) | 6.2 (5.3-7.1) | 0.5 (0.2-0.9) |

| Aged 50-90 y | 3431 | 1.3 (0.8-1.8) | 0.7 (0.4-1.0) | 1.5 (1.0-2.1) | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) | 5.8 (4.5-7.1) | 1.3 (0.9-1.6) |

| Nonpregnant women | |||||||

| Total | 9530 | 13.3 (12.1-14.5) | 3.9 (3.4-4.4) | 13.3 (12.1-14.5) | 4.0 (3.5-4.5) | 26.9 (25.2-28.7) | 5.5 (4.9-6.1) |

| Aged 15-49 y | 5789 | 16.9 (15.3-18.6) | 5.4 (4.7-6.1) | 18.1 (16.5-19.6) | 5.5 (4.8-6.3) | 33.3 (30.8-35.8) | 7.3 (6.3-8.2) |

| Aged 50-90 y | 3741 | 3.5 (2.6-43) | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | 4.1 (3.1-5.0) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 14.5 (12.6-16.4) | 2.1 (1.6-2.7) |

| . | N . | Current WHO threshold . | Current CDC threshold . | Physiologically based thresholds . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % ID . | % IDA . | % ID . | % IDA . | % ID . | % IDA . | ||

| Men | |||||||

| Total | 8413 | 1.1 (0.8-1.4) | 0.4 (0.2-0.5) | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) | 0.5 (0.3-0.7) | 6.1 (5.4-6.8) | 0.8 (0.5-1.0) |

| Aged 15-49 y | 4982 | 1.1 (0.6-1.5) | 0.2 (0.0-0.4) | 1.2 (0.7-1.7) | 0.3 (0.1-0.6) | 6.2 (5.3-7.1) | 0.5 (0.2-0.9) |

| Aged 50-90 y | 3431 | 1.3 (0.8-1.8) | 0.7 (0.4-1.0) | 1.5 (1.0-2.1) | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) | 5.8 (4.5-7.1) | 1.3 (0.9-1.6) |

| Nonpregnant women | |||||||

| Total | 9530 | 13.3 (12.1-14.5) | 3.9 (3.4-4.4) | 13.3 (12.1-14.5) | 4.0 (3.5-4.5) | 26.9 (25.2-28.7) | 5.5 (4.9-6.1) |

| Aged 15-49 y | 5789 | 16.9 (15.3-18.6) | 5.4 (4.7-6.1) | 18.1 (16.5-19.6) | 5.5 (4.8-6.3) | 33.3 (30.8-35.8) | 7.3 (6.3-8.2) |

| Aged 50-90 y | 3741 | 3.5 (2.6-43) | 0.9 (0.6-1.2) | 4.1 (3.1-5.0) | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) | 14.5 (12.6-16.4) | 2.1 (1.6-2.7) |

Unweighted n; all other analyses are weighted. The full NHANES III sample with Hb and SF data was used for this analysis with no data exclusions. ID is defined as follows: current WHO threshold is SF of <15 μg/L; current CDC threshold is SF of ≤15 μg/L; and physiologically based analysis is SF of <25 μg/L for nonpregnant women aged 15 to 49 years and SF of <33 μg/L for nonpregnant women aged 50 to 90 years and men aged 15 to 90 years. Anemia is defined as follows: current WHO threshold is Hb of <130 g/L for men aged 15 to 65 years and Hb of <120 g/L for nonpregnant women aged 15 to 65 years, but we extended it to the age of 90 years for both men and women for this analysis; current CDC thresholds are Hb of <133 g/L for men aged 15 to 17 years, Hb of <135 g/L for men aged ≥18 years, and Hb of 120 g/L for nonpregnant women aged ≥15 years. IDA is defined as both ID and anemia. Current WHO Hb thresholds were used for defining physiologically based IDA.

Discussion

The results of our study provide evidence that reevaluation is needed of WHO and CDC guidelines for a single SF threshold of <15 μg/L to diagnose ID in healthy adults. Our analyses using physiological measures indicate that ID begins at 2 higher and distinct SF concentrations in adults. We find an SF threshold of ∼33 μg/L for men and postmenopausal women. Our earlier study identified a threshold of ∼25 μg/L for premenopausal women, using identical methods from the same NHANES III survey.10 These differences are evident from inspection of the cross-sectional data shown graphically in Figures 2 to 5. The distributions and running medians of plots of Hb and eZnPP with SF for women and men have similar inflection patterns (Figures 2-5). Hb concentrations (1) plateau at higher SF concentrations, (2) begin to decrease at comparable levels for older women and men, and (3) begin to decrease at a still lower level for younger women. eZnPP concentration minima then increase at inflection points as with those for the decreases in Hb with SF. The falls in Hb concentrations, indicating an insufficient iron supply for red blood cell production, and the concurrent rises in eZnPP, demonstrating decreased iron availability for Hb synthesis, occur at SF concentrations well above the WHO and CDC recommendations. The physiological SF threshold of ∼33 μg/L that we have identified for older women and adult men aligns with the threshold of 30 μg/L proposed by the European Hematology Association Specialized Working Group on Red Cell and Iron in 2024.27 Statistical analysis, using RCSs, determines the thresholds for the presence of ID. Compared with the 2 SF thresholds for ID for adults based on physiological measures, the single WHO or CDC recommendation underestimates prevalence of ID in NHANES III by ∼4.7 in men and ∼13.6 percentage points in women aged 15 to 90 years.

The different physiologically based thresholds for ID in premenopausal women compared with those in postmenopausal women and adult men may be interpreted as a consequence of hepcidin regulation of iron homeostasis. Hepcidin had not been discovered at the time of NHANES III,28 but population-based studies29,30 since document lower serum hepcidin concentrations in healthy premenopausal women than in men and postmenopausal women.29,30 Isotopic studies over the past 6 decades, using both radioactive and stable iron isotopes, have consistently shown that iron losses of menstruating women, measured at ∼1.7 mg per day,31 are greater than those of men and postmenopausal women, at ∼1.1 mg per day.31 To maintain body iron balance in women with menstrual iron losses, serum hepcidin decreases, increasing iron absorption. The lower serum hepcidin has the simultaneous effect of increasing mobilization of iron reserves, resulting in a decline in body iron stores and SF. Using age to indicate menstrual status, the effect on iron stores in NHANES III is displayed in the figures with thresholds showing lower SF concentrations in menstruating women compared with men and postmenopausal women. This result suggests that use of iron stores is enhanced at lower amounts of body iron stores (especially among premenopausal women), as reflected in lower SF concentrations. The mechanisms underlying these differences in mobilization at higher and lower levels of body iron stores have not been determined but may involve changes in cellular iron homeostasis within macrophages recycling senescent erythrocytes. Potential pathways include (1) iron-regulatory protein–iron-responsive element control of ferritin synthesis,32 (2) alterations in the delivery of cytosolic iron to cellular ferritin and ferroportin by the iron chaperone proteins poly(rC)-binding proteins 1 and 2,33 (3) modifications in nuclear receptor coactivator 4–dependent ferritinophagy,34 and (4) variations in the proportions and ease of mobilization of iron deposited as ferritin and hemosiderin at different levels of body iron stores.35 A recent report by Galetti et al36 also proposes physiologically based ferritin thresholds using an approach similar to ours, focused on the relationship between SF, serum hepcidin, and upregulation of iron absorption measured using stable iron isotopes. However, their definition of incipient ID was based on iron absorption from hepcidin, which is a much earlier stage than our definition, which is based on identifying ID without anemia from 2 independent iron measures, Hb and eZnPP.

These physiologically based SF thresholds for ID in adults align with our earlier results in children and in pregnant women. Compared with women with menstrual iron losses, children with increased iron requirements for growth have lower SF thresholds for ID together with lower body iron stores that are reflected in SF concentrations.8 During pregnancy, SF thresholds for ID follow serum hepcidin and ferritin concentrations. During the first trimester, ferritin thresholds and hepcidin concentrations are similar to those before pregnancy.9 During the second and third trimesters, the thresholds fall as hepcidin is suppressed to meet the increased iron needs for fetal and placental growth and expansion of the red blood cell mass.9 Overall, these parallels provide evidence that hepcidin regulation of iron homeostasis controls the threshold for ID in healthy adults.

Clinically, the use of the higher physiologically based thresholds would contribute to earlier detection of ID in the adult population in the United States with or without anemia. Adult ID is linked to fatigue, poor physical performance, and diminished work productivity.1 After a diagnosis of ID, the foremost task is to determine and manage the underlying cause of the imbalance between iron requirements and iron supply. Earlier identification of the need for iron in otherwise healthy men and women, combined with measures to increase iron intake,14,37,38 could avoid progression to greater iron deficits and anemia. Improved detection of ID is especially important for the one-third of menstruating women with heavy menstrual bleeding,39,40 and in advance of pregnancy.9 In apparently healthy men and postmenopausal women, earlier detection of ID would allow timely correction of inadequate intake or absorption and identification of gastrointestinal bleeding.41 A variety of lesions at many different sites in the gastrointestinal tract may produce occult blood loss.42 Importantly, in men and postmenopausal women, gastrointestinal malignancy has been reported to be 5-times more common in ID without anemia and 30-times more common in IDA than in those with normal serum iron saturation and Hb levels.43

Our analysis has limitations. First, our study uses older data from the last NHANES (1988-1994) that included 2 independent indicators of ID; the laboratory assays in use have changed. Nonetheless, the most recent pre–COVID-19 NHANES, 2017 to March 2020, measured SF concentrations. For men and postmenopausal women, the SF thresholds corresponding to the initial decline in circulating Hb during 2017 to March 2020 do not differ significantly from those in NHANES during 1988 to 1994 (supplemental Table 1), acknowledging that we do not have sTfR or eZnPP to indicate concurrent increased iron needs. Second, the NHANES III data for apparently healthy adults may include a small number of individuals with inflammatory increases in SF who were not excluded by increased white blood cell counts, CRP, ALT, AST, or SF, but their influence was likely diminished by the use of running medians in the cubic spline analysis. Third, Hb was not adjusted by smoking status although this is recommended for anemia assessment. However, a repeated analysis of smoking-adjusted Hb did not change our results or conclusion. To be consistent with our previous publications,6-10 we did not adjust Hb by smoking status, and excluded individuals with infection, using white blood cell counts >10.0 × 109/L. Fourth, we used age (50 years) as a proxy for menopausal status in women, which may lead to some misclassification given the variability in age at menopause and cessation of menses. Finally, the NHANES data are based on the US population, and international validation of the SF thresholds is needed.

In conclusion, the outcomes of our study indicate that physiological measures detect the presence of ID in adults at 2 separate and distinct SF thresholds that are substantially higher than the single threshold recommended by the WHO and CDC. The results also suggest that, in healthy individuals, using physiological measures to define ID may be more clinically and epidemiologically appropriate than relying on expert opinion and the standard of absent marrow iron stores. The higher physiologically based thresholds for ID could help identify more individuals who would benefit from corrective management. Linkages with clinical and functional outcomes may further highlight optimal SF thresholds for ID.

Acknowledgment

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Authorship

Contribution: Z.M., G.M.B., and O.Y.A. designed the analysis; Z.M. and O.Y.A. analyzed the data; Z.M. and G.M.B. wrote the manuscript; Z.M., O.Y.A., M.E.D.J., and G.M.B. contributed to data interpretation and manuscript revision; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Gary M. Brittenham died on 23 December 2024.

Correspondence: O. Yaw Addo, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Mailstop S107-5, 4770 Buford Hwy, Atlanta, GA 30341-3724; email: lyu6@cdc.gov.

References

Author notes

Data sharing for this article is not applicable. The research was based on deidentified public domain data.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.