Key Points

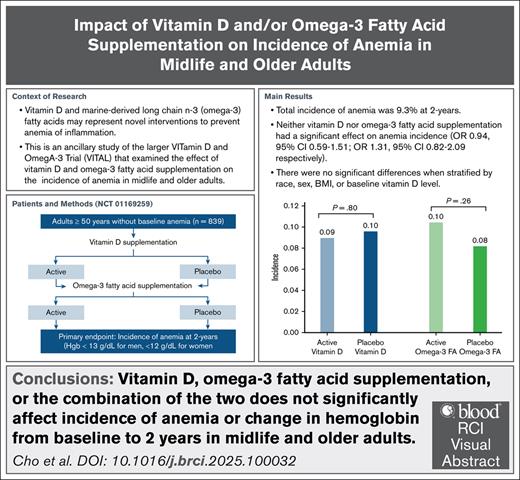

Vitamin D supplementation did not significantly reduce the incidence of anemia at 2 years in older adults.

Omega-3 FA supplementation did not significantly reduce the incidence of anemia at 2 years in older adults.

Visual Abstract

Vitamin D and marine-derived long-chain n-3 (omega-3) fatty acids (FAs) may represent a novel intervention to prevent anemia of inflammation. We report the results of an ancillary study of the larger Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL), which looked at the effect of vitamin D and/or omega-3 FA supplementation on incidence of anemia in midlife and older adults. VITAL is a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial, with a 2 × 2 factorial design. We focus on a subcohort of 839 participants without baseline anemia evaluated at the Boston Clinical and Translational Science Center. The primary end point was incidence of anemia (hemoglobin <13 g/dL for men, and <12 g/dL for women measured, at 2 years). The secondary end point was change in hemoglobin from baseline to 2 years. Incidence of anemia in our cohort was 9.3% over 2 years. Neither vitamin D nor omega-3 FAs had significant effect on anemia incidence (odds ratio [OR], 0.94 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.59-1.51] and 1.31 [95% CI, 0.82-2.09], respectively) or change in hemoglobin from baseline to 2 years. There were no significant differences when stratified by race, sex, body mass index, or baseline vitamin D level. Omega-3 FAs had a statistically significant effect on change in hemoglobin in participants with baseline C-reactive protein >3 mg/L (P interaction = 0.047), whereas vitamin D had an effect in participants with lower than median baseline total fish intake (P interaction = .001). Supplementation with vitamin D or omega-3 FAs, or their combination, did not reduce incidence of anemia in midlife and older adults. The trial was registered at www.ClinicalTrials.gov as #NCT01169259.

Introduction

Anemia is a growing cause of morbidity, mortality, and frailty in our aging population, affecting 10% of older adults aged >65 years and 20% of older adults aged >85 years, according to the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.1 This represents >3 million adults in the United States. Although nutritional deficiency, such as iron deficiency anemia, accounts for approximately one-third of anemia cases in older adults, another one-third is attributed to anemia of inflammation, and the remaining one-third to “unknown” causes. Anemia in these latter groups is thought to be driven by proinflammatory states associated with aging, mediated by hepcidin- and erythropoietin-dependent pathways.2-4

Vitamin D and marine-derived long-chain n-3 (omega-3) fatty acids (FAs) may represent a novel intervention to prevent anemia of inflammation. Multiple translational studies have demonstrated that both vitamin D and omega-3 FAs independently downregulate inflammatory pathways by lowering levels of inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein (CRP), interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α).5-7 There is also evidence to suggest that this correlates clinically, as various studies have shown that low vitamin D levels are associated with higher rates of anemia in older populations.8 Additional analyses have shown that vitamin D supplementation is associated with a reduction in CRP and composite incidence of autoimmune disease.9,10 Regarding omega-3 FAs, a study of 45 participants receiving hemodialysis showed that omega-3 FA supplementation was associated with decreased serum markers of inflammation, such as ferritin and IL-10:IL-6 ratio.11 However, there has not been a randomized clinical trial (RCT) assessing the impact of vitamin D and omega-3 FA supplementation on incident anemia in healthy older adults.

This study addresses an important gap in the literature by using data from the Vitamin D and Omega-3 Trial (VITAL), a large nationwide trial that assessed the impact of vitamin D and omega-3 FA supplementation in older adults.12 In this article, we report the results of an ancillary study assessing the effect of vitamin D and omega-3 FA supplementation on incident anemia in midlife (ages 40 to 65 years old) and older adults, as well as effects on hemoglobin levels.

Methods

Trial design and data collection

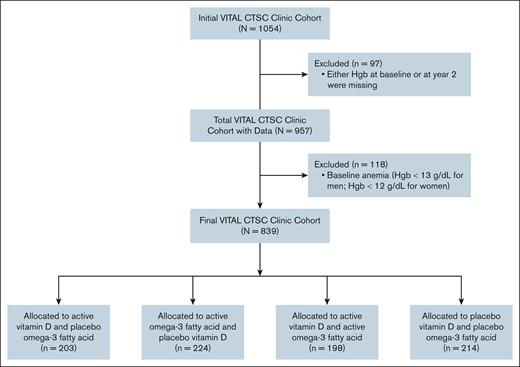

The VITAL study is a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial, with a 2 × 2 factorial design, to assess the effect of vitamin D and omega-3 FA supplementation in midlife and older adults. Participants were randomized into 1 of 4 groups: (1) vitamin D supplement, (2) omega-3 FA supplement, (3) both active supplements, or (4) both placebos. This article focuses on a subcohort of 1054 of 25 871 overall participants enrolled in VITAL, who were evaluated at the Boston Clinical and Translational Science Center (CTSC; Figure 1). Participants in this subcohort consisted of 839 healthy men aged >50 years and women aged >55 years without baseline anemia (see “Statistical Analysis” for definition), and with hemoglobin measures at baseline and year 2.

Flowchart of included participants from the initial VITAL Boston CTSC cohort. Hgb, hemoglobin.

Flowchart of included participants from the initial VITAL Boston CTSC cohort. Hgb, hemoglobin.

Vitamin D was dosed at 2000 IU daily based on studies showing that the average older individual can achieve a serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) level of 75 nmol/L taking 800 to 1000 IU/day.13 Omega-3 FA supplementation was dosed at 1 g/d containing 840 mg of omega-3 FA, including 460 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and 380 mg of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). This dose was based on recommendations from the American Heart Association and prior data suggesting an optimal ratio of EPA to DHA between 1:1 and 1:2.14,15 These treatment doses were determined to balance safety and hypothesized efficacy based on dosing for vitamin D deficiency and cancer and/or cardiovascular disease protection, respectively. Further justification for these doses has been previously described in the larger VITAL studies.12,16,17 Participants received vitamin D and omega-3 supplementation, or their respective placebos, over the course of 2 years during this ancillary study. Vitamin D and omega-3 FA supplements, as well as matching placebos, were provided by Pharmavite LLC and Pronova BioPharma and Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik (BASF), respectively, in the form of calendar packs.

In this ancillary study, blood samples were collected from all participants at baseline (before randomization) and at 2 years (after randomization), including hemoglobin, red blood cell indices, serum creatinine, and 25(OH)D. Inflammatory markers such as IL-6 and CRP were measured and previously reported in a separate ancillary study.9 Participants also received a baseline questionnaire collecting information about medical history, diet, and medication and nutritional supplement use, as well as a follow-up questionnaire at 1 year and 2 years to collect information about compliance to nutritional supplementation.

The institutional review board of Partners HealthCare, Brigham and Women’s Hospital approved VITAL and this ancillary study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Additional details regarding the trial protocol have been published in previous VITAL publications.16,17

Statistical analysis

The primary end point was incidence of anemia defined as hemoglobin <13 g/dL for men and <12 g/dL for women. Secondary outcomes included longitudinal changes in hemoglobin.

Intention-to-treat analyses were assumed for all analyses in this study. Given the 2 × 2 factorial design, analysis was performed by assessing 2 group comparisons assessing the main effects of active vitamin D supplementation vs placebo vitamin D supplementation, and active omega-3 FA supplementation vs placebo omega-3 FA supplementation. Descriptive statistics (mean, median, interquartile range [IQR], and standard deviations [SD] for continuous variables; frequencies for categorical variables) were calculated for baseline characteristics. Differences between vitamin D supplementation and placebo groups in baseline characteristics of participants were assessed using Student t tests (continuous variables, expressed as means), Kruskal-Wallis tests (continuous variables, expressed as median), and χ2 tests (categorical variables). A binary logistic regression using Fisher scoring was used to assess the association between incidence of anemia and intervention groups. Repeated measures analysis was used to measure the overall treatment effect on the change in hemoglobin from baseline to 2 years. Prespecified subgroup analyses were performed on both the logistic regression and repeated measures analysis.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of 839 participants, the mean age was 64.8 years (SD, 6.4 years), and 46.4% were female (Table 1). Most participants were non-Hispanic White (86.1%); the rest of the participants were African American/Black (6.7%), Hispanic (2.8%), Asian (1.8%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (0.6%), or other/unknown (1.9%). Among the cohort, the median hemoglobin was 13.7 g/dL (IQR, 13.1-14.5) with median mean corpuscular volume 91.0 fL (IQR, 88.0-93.0). The median hemoglobin was 14.3 g/dL (IQR, 13.8-15.0) for men and 13.1 g/dL (IQR, 12.6-13.6) for women. Other baseline characteristics included creatinine 0.82 mg/dL (IQR, 0.71-0.94), serum 25(OH)D 28.0 ng/mL (IQR, 22.0-34.0), IL-6 2.3 pg/mL (IQR, 1.7-3.4), and CRP 1.2 mg/L (IQR, 0.6-2.6). Participants were evenly divided among 4 treatment groups: active vitamin D/placebo omega-3 FA (n = 203 [24.2%]), active omega-3 FA/placebo vitamin D (n = 224 [26.7%]), active vitamin D/active omega-3 FA (n = 198 [23.6%]), and placebo vitamin D/placebo omega-3 FA (n = 214 [25.5%]). There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the dual placebo, vitamin D only, omega-3 only, and vitamin D/omega-3 groups.

Baseline characteristics of participants

| Baseline characteristic . | Total cohort (N = 839) . | Active vitamin D (n = 203) . | Active omega-3 (n = 224) . | Active vitamin D + omega-3 (n = 198) . | Both placebo (n = 214) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 64.8 (6.4) | 64.5 (6.0) | 65.0 (6.5) | 64.5 (6.5) | 65.1 (6.6) | .67 |

| Median (IQR) | 64.3 (60.3-69.0) | 64.2 (60.3-68.2) | 64.3 (60.1-68.9) | 63.8 (60.3-69.2) | 64.5 (60.4-69.2) | .83 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 450 (53.6) | 111 (54.7) | 116 (51.8) | 105 (53.0) | 118 (55.1) | .89 |

| Female | 389 (46.4) | 92 (45.3) | 108 (48.2) | 93 (47.0) | 96 (44.9) | |

| Race/ethnicity∗,† | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 709 (86.1) | 169 (84.1) | 181 (83.0) | 171 (88.1) | 188 (89.5) | .16 |

| Non-White‡ | 114 (13.9) | 32 (15.9) | 37 (17.0) | 23 (11.9) | 22 (10.5) | |

| BMI§ | 26.3 (24.0-29.6) | 26.4 (23.7-29.0) | 26.6 (24.4-30.3) | 26.0 (24.1-29.2) | 25.7 (23.6-29.7) | .17 |

| Hemoglobin,§ g/dL | 13.7 (13.1-14.5) | 13.8 (13.2-14.4) | 13.7 (13.1-14.4) | 13.7 (13.0-14.5) | 13.8 (13.0-14.6) | .91 |

| MCV,§,‖ fL | 91.0 (88.0-93.0) | 91.0 (88.0-93.0) | 91.0 (88.5-93.0) | 91.0 (88.0-93.0) | 90.5 (88.0-93.0) | .60 |

| 25(OH)-vitamin D,§ ng/mL | 28.0 (22.0-34.0) | 27.0 (22.0-34.0) | 29.0 (20.5-34.0) | 28.0 (22.0-33.0) | 29.0 (24.0-33.0) | .23 |

| Cr,§ mg/dL | 0.82 (0.71-0.94) | 0.80 (0.70-0.93) | 0.83 (0.72-0.95) | 0.84 (0.72-0.93) | 0.82 (0.71-0.97) | .53 |

| IL-6,§,¶ pg/mL | 2.3 (1.7-3.4) | 2.5 (1.8-3.8) | 2.4 (1.8-3.4) | 2.1 (1.7-3.3) | 2.1 (1.7-3.1) | .06 |

| CRP,‡,# mg/L | 1.2 (0.6-2.6) | 1.0 (0.5-2.5) | 1.4 (0.6-2.8) | 1.3 (0.6-2.5) | 1.1 (0.6-2.4) | .36 |

| Total fish intake, servings per wk | 1.87 (0.93-2.93) | 1.87 (0.93-2.93) | 1.87 (1.00-2.47) | 1.93 (1.40-3.00) | 1.93 (1.00-2.93) | .34 |

| Baseline characteristic . | Total cohort (N = 839) . | Active vitamin D (n = 203) . | Active omega-3 (n = 224) . | Active vitamin D + omega-3 (n = 198) . | Both placebo (n = 214) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 64.8 (6.4) | 64.5 (6.0) | 65.0 (6.5) | 64.5 (6.5) | 65.1 (6.6) | .67 |

| Median (IQR) | 64.3 (60.3-69.0) | 64.2 (60.3-68.2) | 64.3 (60.1-68.9) | 63.8 (60.3-69.2) | 64.5 (60.4-69.2) | .83 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 450 (53.6) | 111 (54.7) | 116 (51.8) | 105 (53.0) | 118 (55.1) | .89 |

| Female | 389 (46.4) | 92 (45.3) | 108 (48.2) | 93 (47.0) | 96 (44.9) | |

| Race/ethnicity∗,† | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 709 (86.1) | 169 (84.1) | 181 (83.0) | 171 (88.1) | 188 (89.5) | .16 |

| Non-White‡ | 114 (13.9) | 32 (15.9) | 37 (17.0) | 23 (11.9) | 22 (10.5) | |

| BMI§ | 26.3 (24.0-29.6) | 26.4 (23.7-29.0) | 26.6 (24.4-30.3) | 26.0 (24.1-29.2) | 25.7 (23.6-29.7) | .17 |

| Hemoglobin,§ g/dL | 13.7 (13.1-14.5) | 13.8 (13.2-14.4) | 13.7 (13.1-14.4) | 13.7 (13.0-14.5) | 13.8 (13.0-14.6) | .91 |

| MCV,§,‖ fL | 91.0 (88.0-93.0) | 91.0 (88.0-93.0) | 91.0 (88.5-93.0) | 91.0 (88.0-93.0) | 90.5 (88.0-93.0) | .60 |

| 25(OH)-vitamin D,§ ng/mL | 28.0 (22.0-34.0) | 27.0 (22.0-34.0) | 29.0 (20.5-34.0) | 28.0 (22.0-33.0) | 29.0 (24.0-33.0) | .23 |

| Cr,§ mg/dL | 0.82 (0.71-0.94) | 0.80 (0.70-0.93) | 0.83 (0.72-0.95) | 0.84 (0.72-0.93) | 0.82 (0.71-0.97) | .53 |

| IL-6,§,¶ pg/mL | 2.3 (1.7-3.4) | 2.5 (1.8-3.8) | 2.4 (1.8-3.4) | 2.1 (1.7-3.3) | 2.1 (1.7-3.1) | .06 |

| CRP,‡,# mg/L | 1.2 (0.6-2.6) | 1.0 (0.5-2.5) | 1.4 (0.6-2.8) | 1.3 (0.6-2.5) | 1.1 (0.6-2.4) | .36 |

| Total fish intake, servings per wk | 1.87 (0.93-2.93) | 1.87 (0.93-2.93) | 1.87 (1.00-2.47) | 1.93 (1.40-3.00) | 1.93 (1.00-2.93) | .34 |

Data are presented as n (%) and median (IQR) unless otherwise specified.

BMI, body mass index; Cr, creatinine; MCV, mean corpuscular volume.

P value calculated using non-Hispanic White as the reference group.

Sample size for race/ethnicity of 823 with 16 missing data points.

Non-White includes African American, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian/Alaskan Native, and other/unknown.

P values were calculated using nonparametric tests given nonnormal distributions.

Sample size for MCV of 838 with 1 missing data point.

Sample size for IL-6 of 563 with 276 missing data points.

Sample size for CRP of 833 with 6 missing data points.

For the overall VITAL study, compliance was defined as taking more than two-thirds of the prescribed supplements. For active vitamin D, compliance was noted to be 90.2% at 1 year and 87.6% at 2 years (SD, 20.3 and 24.9, respectively), and 89.8% and 87.0% (SD, 20.9 and 25.4, respectively) for placebo vitamin D. Compliance for active omega-3 FAs was noted to be 89.7% at 1 year and 87.0% at 2 years (SD, 21.0 and 25.5, respectively), and 90.2% and 87.6% (SD, 20.1 and 24.7, respectively) for placebo omega-3 FAs. Comprehensive compliance data can be found in the supplemental Materials of previous VITAL publications.16,17

Incidence of anemia

The incidence of anemia in our overall cohort was 9.3% (n = 78/839) over the 2 years follow-up period. The incidence of anemia in participants who received active vitamin D was 9.0% (n = 36/401), and 9.6% in participants who received placebo vitamin D (n = 42/438). There was no significant difference in incidence of anemia when comparing participants who received active vs placebo vitamin D (odds ratio [OR], 0.94; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.59-1.51). Similarly, the incidence of anemia in participants who received active omega-3 FAs was 10.4% (n = 44/422) compared with 8.2% in participants who received placebo omega-3 FAs (n = 34/417). There was no significant difference in incidence of anemia between these 2 groups (OR, 1.31; 95% CI, 0.82-2.09). Stratification by age (50-64, 65-74, and ≥75 years), race (White vs non-White), sex, body mass index (<25, 25-30, and ≥30 kg/m2), baseline 25(OH)D level (<20 and ≥20 ng/mL), total dietary fish intake, and baseline CRP did not demonstrate any evidence of significant effect modification (Table 2).

Incidence of anemia at year 2 by vitamin D and omega-3 supplementation

| Subgroup . | Active vitamin D (n = 401), n (%) . | Placebo vitamin D (n = 438), n (%) . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . | Active omega-3 (n = 422), n (%) . | Placebo omega-3 (n = 417), n (%) . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort | 36 (9.0) | 42 (9.6) | 0.94 (0.59-1.51) | .80 | 44 (10.4) | 34 (8.2) | 1.31 (0.82-2.09) | .26 |

| Age, y | .73∗ | .32∗ | ||||||

| 50-64 | 19/220 (8.6) | 23/231 (10.0) | 0.86 (0.45-1.62) | .63 | 21/228 (9.2) | 21/223 (9.4) | 0.97 (0.51-1.83) | .92 |

| 65-74 | 14/160 (8.8) | 15/174 (8.6) | 1.05 (0.49-2.26) | .91 | 19/164 (11.6) | 10/170 (5.9) | 2.09 (0.94-4.66) | .07 |

| ≥75 | 3/21 (14.3) | 4/33 (12.1) | 1.15 (0.22-5.93) | .87 | 4/30 (13.3) | 3/24 (12.5) | 0.95 (0.18-5.05) | .95 |

| Sex | .85∗ | .13∗ | ||||||

| Male | 19/216 (8.8) | 21/234 (9.0) | 0.99 (0.51-1.89) | .96 | 19/221 (8.6) | 21/229 (9.2) | 0.93 (0.48-1.78) | .82 |

| Female | 17/185 (9.2) | 21/204 (10.3) | 0.90 (0.46-1.78) | .77 | 25/201 (12.4) | 13/188 (6.9) | 1.93 (0.96-3.90) | .07 |

| Race† | .36∗ | .60∗ | ||||||

| White | 32/340 (9.4) | 33/369 (8.9) | 1.07 (0.64-1.79) | .80 | 35/352 (9.9) | 30/357 (8.4) | 1.2 (0.72-2.01) | .48 |

| Non-White | 4/55 (7.3) | 8/59 (13.6) | 0.57 (0.15-2.10) | .39 | 8/60 (13.3) | 4/54 (7.4) | 1.8 (0.49-6.70) | .38 |

| BMI | .62∗ | .19∗ | ||||||

| <25 | 17/141 (12.1) | 19/154 (12.3) | 1.00 (0.49-2.01) | .99 | 17/136 (12.5) | 19/159 (12.0) | 1.01 (0.50-2.04) | .98 |

| 25 to <30 | 13/182 (7.1) | 12/176 (6.8) | 1.03 (0.45-2.34) | .95 | 15/186 (8.1) | 10/172 (5.8) | 1.37 (0.59-3.17) | .47 |

| ≥30 | 6/78 (7.7) | 11/108 (10.2) | 0.71 (0.25-2.04) | .52 | 12/100 (12.0) | 5/86 (5.8) | 2.1 (0.71-6.33) | .18 |

| Baseline vitamin D, ng/mL | .81∗ | .54∗ | ||||||

| <20 | 7/66 (10.6) | 9/71 (12.7) | 0.78 (0.26-2.33) | .65 | 9/76 (11.8) | 7/61 (11.5) | 1.05 (0.35-3.22) | .93 |

| ≥20 | 29/335 (8.7) | 33/367 (9.0) | 0.96 (0.57-1.63) | .89 | 35/346 (10.1) | 27/356 (7.6) | 1.38 (0.82-2.34) | .23 |

| Total fish intake‡ | .36∗ | .13∗ | ||||||

| Below median | 17/162 (10.5) | 16/183 (8.7) | 1.29 (0.62-2.66) | .49 | 21/164 (12.8) | 12/181 (6.6) | 2.13 (1.01-4.51) | .047∗ |

| Median or higher | 17/216 (7.9) | 22/232 (9.5) | 0.82 (0.42-1.59) | .56 | 20/234 (8.5) | 19/214 (8.9) | 0.96 (0.50-1.86) | .91 |

| CRP,§mg/L | .58∗ | .63∗ | ||||||

| <1 | 19/177 (10.7) | 18/180 (10.0) | 1.10 (0.55-2.17) | .79 | 19/163 (11.7) | 18/194 (9.3) | 1.27 (0.64-2.51) | .50 |

| 1-3 | 10/136 (7.4) | 13/157 (8.3) | 0.88 (0.37-2.08) | .77 | 13/162 (8.0) | 10/131 (7.6) | 1.05 (0.44-2.49) | .91 |

| >3 | 7/86 (8.1) | 10/97 (10.3) | 0.83 (0.30-2.33) | .73 | 11/93 (11.8) | 6/90 (6.7) | 1.91 (0.67-5.42) | .23 |

| Subgroup . | Active vitamin D (n = 401), n (%) . | Placebo vitamin D (n = 438), n (%) . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . | Active omega-3 (n = 422), n (%) . | Placebo omega-3 (n = 417), n (%) . | OR (95% CI) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort | 36 (9.0) | 42 (9.6) | 0.94 (0.59-1.51) | .80 | 44 (10.4) | 34 (8.2) | 1.31 (0.82-2.09) | .26 |

| Age, y | .73∗ | .32∗ | ||||||

| 50-64 | 19/220 (8.6) | 23/231 (10.0) | 0.86 (0.45-1.62) | .63 | 21/228 (9.2) | 21/223 (9.4) | 0.97 (0.51-1.83) | .92 |

| 65-74 | 14/160 (8.8) | 15/174 (8.6) | 1.05 (0.49-2.26) | .91 | 19/164 (11.6) | 10/170 (5.9) | 2.09 (0.94-4.66) | .07 |

| ≥75 | 3/21 (14.3) | 4/33 (12.1) | 1.15 (0.22-5.93) | .87 | 4/30 (13.3) | 3/24 (12.5) | 0.95 (0.18-5.05) | .95 |

| Sex | .85∗ | .13∗ | ||||||

| Male | 19/216 (8.8) | 21/234 (9.0) | 0.99 (0.51-1.89) | .96 | 19/221 (8.6) | 21/229 (9.2) | 0.93 (0.48-1.78) | .82 |

| Female | 17/185 (9.2) | 21/204 (10.3) | 0.90 (0.46-1.78) | .77 | 25/201 (12.4) | 13/188 (6.9) | 1.93 (0.96-3.90) | .07 |

| Race† | .36∗ | .60∗ | ||||||

| White | 32/340 (9.4) | 33/369 (8.9) | 1.07 (0.64-1.79) | .80 | 35/352 (9.9) | 30/357 (8.4) | 1.2 (0.72-2.01) | .48 |

| Non-White | 4/55 (7.3) | 8/59 (13.6) | 0.57 (0.15-2.10) | .39 | 8/60 (13.3) | 4/54 (7.4) | 1.8 (0.49-6.70) | .38 |

| BMI | .62∗ | .19∗ | ||||||

| <25 | 17/141 (12.1) | 19/154 (12.3) | 1.00 (0.49-2.01) | .99 | 17/136 (12.5) | 19/159 (12.0) | 1.01 (0.50-2.04) | .98 |

| 25 to <30 | 13/182 (7.1) | 12/176 (6.8) | 1.03 (0.45-2.34) | .95 | 15/186 (8.1) | 10/172 (5.8) | 1.37 (0.59-3.17) | .47 |

| ≥30 | 6/78 (7.7) | 11/108 (10.2) | 0.71 (0.25-2.04) | .52 | 12/100 (12.0) | 5/86 (5.8) | 2.1 (0.71-6.33) | .18 |

| Baseline vitamin D, ng/mL | .81∗ | .54∗ | ||||||

| <20 | 7/66 (10.6) | 9/71 (12.7) | 0.78 (0.26-2.33) | .65 | 9/76 (11.8) | 7/61 (11.5) | 1.05 (0.35-3.22) | .93 |

| ≥20 | 29/335 (8.7) | 33/367 (9.0) | 0.96 (0.57-1.63) | .89 | 35/346 (10.1) | 27/356 (7.6) | 1.38 (0.82-2.34) | .23 |

| Total fish intake‡ | .36∗ | .13∗ | ||||||

| Below median | 17/162 (10.5) | 16/183 (8.7) | 1.29 (0.62-2.66) | .49 | 21/164 (12.8) | 12/181 (6.6) | 2.13 (1.01-4.51) | .047∗ |

| Median or higher | 17/216 (7.9) | 22/232 (9.5) | 0.82 (0.42-1.59) | .56 | 20/234 (8.5) | 19/214 (8.9) | 0.96 (0.50-1.86) | .91 |

| CRP,§mg/L | .58∗ | .63∗ | ||||||

| <1 | 19/177 (10.7) | 18/180 (10.0) | 1.10 (0.55-2.17) | .79 | 19/163 (11.7) | 18/194 (9.3) | 1.27 (0.64-2.51) | .50 |

| 1-3 | 10/136 (7.4) | 13/157 (8.3) | 0.88 (0.37-2.08) | .77 | 13/162 (8.0) | 10/131 (7.6) | 1.05 (0.44-2.49) | .91 |

| >3 | 7/86 (8.1) | 10/97 (10.3) | 0.83 (0.30-2.33) | .73 | 11/93 (11.8) | 6/90 (6.7) | 1.91 (0.67-5.42) | .23 |

Refers to P interaction.

Missing data points for race for active vitamin D (n = 6), placebo vitamin D (n = 10), active omega-3 FAs (n = 10), and placebo omega-3 FAs (n = 6).

Missing data points for fish intake by group were as follows: n = 23 (active vitamin D), n = 23 (placebo vitamin D), n = 24 (active omega-3 FAs), and n = 22 (placebo omega-3 FAs).

Missing data points for CRP by group were as follows: n = 2 (active vitamin D), n = 4 (placebo vitamin D), n = 4 (active omega-3 FAs), and n = 2 (placebo omega-3 FAs).

There were no significant differences in incidence of anemia by 4 treatment groups (active vitamin D + placebo omega-3 FAs, active omega-3 FAs + placebo vitamin D, active vitamin D + active omega-3 FAs, placebo vitamin D + placebo omega-3 FAs; OR, 0.94 [95% CI, 0.47-1.90] for active vitamin D only; OR, 1.31 [95% CI, 0.69-2.49] for active omega-3 FAs only; OR, 1.23 [95% CI, 0.63-2.41] for both active vitamin D + omega-3 FAs using the placebo vitamin D + omega-3 FAs group as reference).

Changes in hemoglobin

Among the 839 participants without baseline anemia, the median hemoglobin was 13.5 g/dL (IQR, 12.8-14.4) at 2 years, 14.2 g/dL for men (IQR, 13.5-14.9) and 12.9 g/dL (IQR, 12.4-13.5) for women. The median baseline hemoglobin levels for participants who received active vitamin D vs placebo vitamin D were 13.7 g/dL (IQR, 13.1-14.4) and 13.8 g/dL (13.1-14.5), respectively. At 2 years, the median hemoglobin significantly decreased in both groups to 13.5 g/dL (IQR, 12.9-14.4) and 13.6 g/dL (IQR, 12.8-14.4), respectively. Vitamin D supplementation did not have a significant effect on hemoglobin levels from baseline to 2 years (overall treatment effect, 0.01 g/dL [95% CI, −0.09 to −0.11]; P = .81).

Similarly, the median baseline hemoglobin levels for participants who received active omega-3 FAs vs placebo omega-3 FAs were 13.7 g/dL (IQR, 13.0-14.4) and 13.8 g/dL (IQR, 13.1-14.5), respectively. At 2 years, the median hemoglobin significantly decreased in both groups to 13.6 g/dL (IQR, 12.8-14.4) and 13.5 g/dL (IQR, 12.8-14.4), respectively. Omega-3 FA supplementation did not have a significant effect on hemoglobin levels from baseline to 2 years (overall treatment effect, 0.04 g/dL [95% CI, –0.06 to 0.14]; P = .41). There were no significant effects when stratifying by age, sex, body mass index, race, or baseline vitamin D (supplemental Table 1). There was a borderline significant effect on the change in hemoglobin from baseline to 2 years with omega-3 FA supplementation when assessing the 183 participants with baseline CRP >3 mg/L (0.24 g/dL [95% CI, 0.03-0.45]; P = .025; P interaction = .047). This effect did not extend to participants with preexisting anemia (n = 118) and baseline CRP >3 mg/L (n = 28, 17 receiving placebo omega-3 FAs and 11 receiving active omega-3 FAs; 0.05 g/dL [95% CI, 0.60-0.70]; P interaction = .45).

There was also a significant effect on the change in hemoglobin with vitamin D supplementation, but not omega-3 FA supplementation, based on baseline total fish intake (P interaction = .001; supplemental Table 1). For those with below median baseline total fish intake, the change in hemoglobin from baseline to 2 years was 0.17 g/dL (95% CI, –0.32 to −0.02), whereas for those with total fish intake equal to or above the median had a change of 0.16 g/dL (95% CI, 0.03-0.30).

When comparing across the 4 treatment groups, the change in hemoglobin was not significantly affected by either vitamin D supplementation, omega-3 FA supplementation, or the combination of the 2 (P = .66, P = .99, and P = .44, respectively).

Discussion

Our ancillary analysis of the larger VITAL study is the first RCT, to our knowledge, to study the effects of vitamin D and omega-3 FA supplementation in healthy midlife and older adults. Our findings showed that supplementation with vitamin D, omega-3 FAs, or the combination of the 2 did not reduce the incidence of anemia in our patient population. There was also no significant difference in hemoglobin levels at 2 years with vitamin D and/or omega-3 FA supplementation.

We had anticipated that participants who were more prone to proinflammatory states, such as those with obesity or baseline elevated levels of CRP, might better respond to supplementation. Our subgroup analysis did show a significant increase in change in hemoglobin from baseline to 2 years with omega-3 FA supplementation for those with CRP >3. However, omega-3 FA supplementation did not affect the incidence of anemia, making the clinical significance of this change unclear. There was also a statistically significant difference in change in hemoglobin based on baseline total fish intake with vitamin D supplementation. This may be due to the positive effect on dietary fat intake on vitamin D absorption,18 but is clinically difficult to interpret in the setting of an otherwise negative trial. The rest of our subgroup analyses did not show any difference, and there were no other significant differences in incidence of anemia or hemoglobin level at baseline vs 2 years in any of the intervention groups.

Anemia in older populations is thought to be driven by inflammation associated with aging.2-4 Several studies support the role of inflammation in anemia in older adults: the InCHIANTI study looked at inflammatory markers and anemia in >1000 adults aged >65 years in Italy.2 The study found that higher inflammatory markers were associated with depressed levels of erythropoietin in participants with anemia, suggesting that chronic inflammation was a driving factor. The exact mechanism by which inflammation drives anemia is unknown, but likely includes a combination of decreased red blood cell survival, decreased erythropoiesis, and dysregulation of iron metabolism. The most investigated mediator is hepcidin, a 25-amino-acid peptide synthesized by the liver that blocks intestinal iron absorption and iron release from macrophages, and responds to proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-1β. A study by Wacka et al3 showed that elevated levels of IL-1β are associated with lower hemoglobin, whereas another study by Herpich et al4 showed that higher levels of IL-6, CRP, and IL-6:IL-10 were associated with increased frailty and anemia in older adults.

Both vitamin D and omega-3 FAs have generated interest as prophylaxis and treatment for various inflammatory conditions, including anemia of inflammation, due to their modulating roles in various inflammatory pathways. Translational studies have shown that vitamin D lowers hepcidin both by decreasing IL-6 and IL-1β levels and by downregulating hepcidin antimicrobial peptide gene messenger RNA expression.5,6 Vitamin D is also thought to mediate hepcidin-independent pathways by affecting NF-κβ expression, although fewer studies have investigated this mechanism. Omega-3 FAs, including EPA and DHA, have been shown to similarly lower levels of inflammatory markers such as IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α in both in vitro studies7 and in vivo studies,19,20 although there are other studies that have not found this effect.21,22

However, our study importantly suggests that these findings may not be generalizable to healthy midlife and older adults. Although there have been some studies assessing the role of vitamin D and/or omega-3 FAs on anemia in specific patient populations, such as those with chronic kidney disease or HIV, this is the first large RCT, to our knowledge, to assess vitamin D and omega-3 FA supplementation in a relatively healthy population of older adults. It is possible that vitamin D and/or omega-3 FA supplementation could be beneficial in older adults with more comorbidities. Unfortunately, the incidence of vitamin D deficiency was too low within our sample to perform a subgroup analysis. It is also possible that our findings may be partially explained by the relatively low numbers of older adults with anemia in our population. The Boston CTSC sample of 839 participants is relatively small compared with the total VITAL cohort of 25 000. Unfortunately, no complete blood count data were available for VITAL participants in the larger parent trial.

Given the total incidence of anemia in our sample of 9.3% is slightly below the average rate of anemia in nonhospitalized midlife to older adults, it is possible that there were not enough events to see any significant difference.1 It is also possible that, in a larger cohort with baseline CRP ≥3 mg/L, there might have been a detectable difference in incidence of anemia or change in hemoglobin from baseline to 2 years with omega-3 FA supplementation. This would be in line with the known mechanism of omega-3 FAs in reducing inflammation, and therefore affecting erythropoiesis. However, it is also possible that the effects are too minimal for clinical significance even in a larger population.

Our findings align with prior analyses of the VITAL study, including analysis of the effect of vitamin D and omega-3 FA supplementation on biomarkers of systemic inflammation, including CRP, IL-6, IL-10, and TNF-α.9 Although a study by Dong et al showed that among the Boston cohort of participants enrolled in VITAL (n = 1054), vitamin D supplementation was associated with significantly lower levels of CRP compared with placebo at 2 years, this effect was attenuated by 4 years. Dong et al also found no other significant changes in markers of inflammation with vitamin D or omega-3 FA supplementation at 2 or 4 years, suggesting no long-lasting impact on markers of inflammation. An additional ancillary VITAL study looked at the impact of vitamin D and omega-3 FA supplementation in frailty among older participants.23 This study also found that there were no significant changes in the Rockwood frailty index, of which anemia is one of 36 components, with supplementation.

Interestingly, our subgroup analysis did not show any significant difference in incidence of anemia by race/ethnicity, or any differences in the effect of vitamin D and/or omega-3 FA supplementation on incidence of anemia by race/ethnicity, despite known significant racial and ethnic disparities in incidence of anemia. Several studies have shown that non-Hispanic Black participants have 3 times the rate of anemia of non-Hispanic White participants, even after adjusting for other causes of anemias such as iron deficiency and thalassemia.24-26 Ancillary analyses of the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey further showed that anemia of inflammation was 7 times more common in non-Hispanic Black participants compared with their White counterparts, but that the effect was decreased after accounting for vitamin D deficiency.27 However, this difference may be accounted for by the relatively high proportion of non-Hispanic White participants in our sample (86.1%, compared with 47.8% in Boston according to the most recent US Census Bureau data), as well as the smaller sample sizes and power of these subgroup analyses.28

Our study has several limitations. The VITAL randomized trial assessed 1 fixed study dose of vitamin D and omega-3 FA supplementation, so we cannot address whether higher doses of vitamin D or omega-3 FAs would result in changes in incidence of anemia in older adults. In addition, the follow-up period of 2 years may not have been sufficiently long to assess a change in anemia incidence. It is possible that with a longer follow-up period, a significant change may have been detected. Finally, although we did not provide CTSC-specific compliance data, the compliance data for the overall VITAL cohort should reflect the CTSC cohort, if not underestimate compliance data given the in-person visits required for the CTSC cohort alone.

In this ancillary study of VITAL, we demonstrate that vitamin D and omega-3 FA supplementation did not decrease the incidence of anemia in midlife or older adults. As such, with respect to anemia risk, there is no evidence to recommend adding vitamin D or omega-3 FA supplements to the already-high pill burdens in our healthy older populations. Further studies may assess the effect of vitamin D and omega-3 FA supplementation on populations at higher risk of developing anemia of inflammation, including participants with chronic kidney disease or autoimmune conditions, as well as those with preexisting anemia of inflammation, to assess for possible effects on hemoglobin levels.

Acknowledgments

This ancillary study of the Vitamin D and Omega-3 (VITAL) trial was supported by R01 HL131674 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The broader VITAL trial was funded by the National Institute of Health grants U01 CA138962 and R01 CA138962 from the National Cancer Institute, and R01 AT011729 from the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.

Authorship

Contribution: H.L.C. wrote the manuscript; C.L. performed the statistical testing; N.B. was the principal investigator and wrote the subgroup protocol, with contributions from J.E.M., N.R.C., I.-M.L., and J.E.B.; and all authors contributed to the design of the statistical analysis plan.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Hae Lin Cho, Internal Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis St, Boston, MA 02115; email: hlcho@mgb.org.

References

Author notes

Deidentified individual participant data may be made accessible upon request from author Nancy Berliner (nberliner@bwh.harvard.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.