Key Points

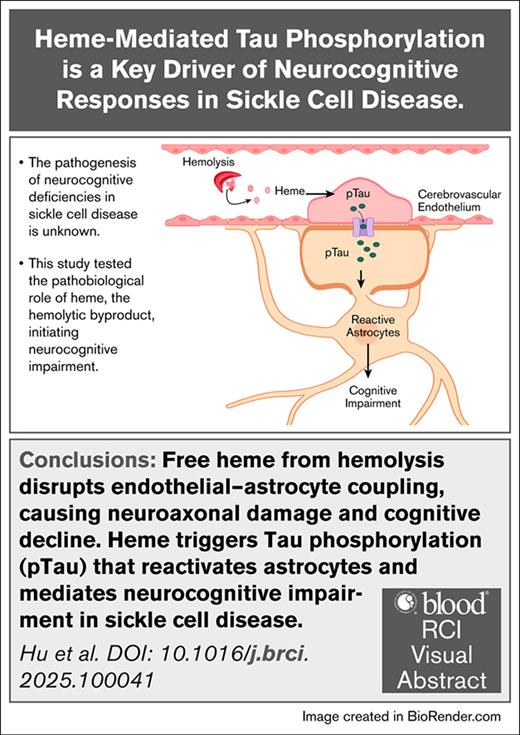

Free heme from hemolysis disrupts endothelial–astrocyte coupling, causing neuroaxonal damage and cognitive decline.

Heme triggers pTau that reactivates astrocytes and mediates neurocognitive impairment in SCD.

Visual Abstract

Neurocognitive impairment comprising microstructural neuroaxonal damage associated with cognitive deficiencies are common in individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD). Hemolysis is a key component of SCD, however, its role in the neurocognitive impairment is not known. We discovered that plasma levels of neurofilament light chain (NFL), a marker for neuroaxonal injury, and phosphorylated Tau (pTau), a biomarker for cognitive impairment, are elevated in patients with SCD. Interestingly, both NFL and pTau are associated with markers of hemolysis. Thus, we tested whether heme, the elevated hemolytic byproduct, contributes to neurocognitive impairment in SCD. Increased circulating heme resulted in significant induction of pTau in the cerebrovascular endothelium, the adjacent astrocytes and in the plasma of the SCD (SS) mice. Heme infusion exacerbated microstructural neuroaxonal damage and substantially impaired the cognitive responses in the SS compared to vehicle-injected normal controls. Sickle bone marrow chimera mice lacking Tau expression (SSTau˗/˗) showed significant improvement in structural and behavioral neurocognitive responses compared to control mice (SSTau+/+) following heme challenge. Our study identifies Tau as a crucial intermediate that connects hemolysis to neurovascular damage and cognitive impairment in SCD and suggests pTau may be developed as an important diagnostic and therapeutic target for neurocognitive complications in SCD.

Introduction

Cerebrovascular complications in sickle cell disease (SCD) are associated with cognitive impairment, characterized by deficits in executive function and memory. About 50% of patients with SCD exhibit delays in early markers of cognition and expressive language, along with difficulties in processing speed and working memory.1,2 The most common cerebrovascular lesions in SCD patients are silent cerebral infarctions diagnosed by T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in combination with diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and diffusion weighed imaging. These widespread microstructural lesions that are located primarily in the frontoparietal deep white matter border areas are associated with lower full-scale intelligent quotient and cognitive test scores in patients with SCD compared to healthy controls.3,4 We have found that SCD mice are a helpful model to study the mechanisms underlying cognitive deficits in SCD. We have reported that the deterioration of learning and memory function in preclinical SCD mice compared to nonsickle mice are associated with (1) reduced fractional anisotropy (FA), a DTI-derived metric that indicates microstructural neuroaxonal integrity and (2) increased reactivity of astrocytes, the cells that interconnect cerebral microvasculature with neurons.5,6 We have then set out to explore whether hemolysis is linked to cognitive dysfunction in SCD mice.

In SCD, intravascular hemolysis from premature destruction of erythrocytes7 releases cell-free hemoglobin into the plasma, which quickly undergoes auto-oxidation releasing free heme.8,9 Heme causes cytoskeletal derangement10,11 altering endothelial homeostasis that modulates adjacent astrocyte functioning. Activation of microvascular endothelium by heme can potentially trigger astrocyte reactivation and regulate neuroaxonal integrity.12-14

Tau, a microtubule-associated protein encoded by the MAPT gene, undergoes several posttranslational modifications, including hyperphosphorylation, oligomeric aggregation, and propagation, which collectively promote neuropathological events.15 Phosphorylation of Tau, specifically in the serine and threonine residues, triggers detachment of Tau from microtubules. The hyperphosphorylated and aggregated forms of Tau, including pTau181, pTau205, and pTau217 are transmissible among different cerebral components.16 Several clinical studies have shown that plasma concentration of various phosphorylated Tau (pTau) isoforms, such as pTau217, is associated with cognitive function in individuals with Alzheimer disease or vascular dementia.17 We hypothesized that heme could mediate the phosphorylation of Tau in cerebral microvascular endothelial cells, resulting in the propagation of Tau aggregates leading to astrocyte reactivation and impaired neurocognitive function. In this study, we used plasma samples from SCD patients and humanized transgenic SCD mice to determine the role of extracellular heme-mediated Tau phosphorylation in maintaining neuroaxonal integrity in SCD. Our data identifies a hemolysis driven mechanism regulating neurocognitive function in SCD.

Study design

Refer to supplemental Materials for detailed methodology.

Human plasma samples

Biorepository plasma samples from the Sickle Cell Registry at University of Pittsburgh were used (institutional review board no. CR19030018-024). These samples were obtained from individuals with SCD and healthy nonsickle African American control individuals at steady state, that is, in the absence of acute complications.

Animals

The Townes mice with SCD (SS) and the normal control (AA) mice (stock no. 013071), Tau-knockout (Tau˗/˗, stock no. 007521) and wild-type control (B6; Tau+/+, stock no. 000664) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and maintained at the University of Pittsburgh vivarium. All experiments were performed following Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval (protocol nos. 22010095 and 24126048). Both male and female mice (10-12 weeks old) were used.

Bone marrow transplantation

The Tau-knockout (Tau˗/˗) and Tau-expressing (Tau+/+) wild-type mice were transplanted with whole bone marrow cells from SS or AA mice to generate chimeric mouse strains possessing hematological characteristics of SS (SSTau˗/˗ and SSTau+/+), or AA (AATau+/+).

DTI

Ex-vivo DTI was performed using a Bruker AV3HD 11.7 Tesla/89 mm vertical bore microimaging system and ParaVision 6.0.1 (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA). DTI data were analyzed with DSI Studio to determine mean FA.

Immunofluorescence

Paraformaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded parietal brain tissue sections were assessed for pTau, astrocyte marker (Aquaporin 4, AQP4), endothelial cell marker (CD31), neurofilament H (SMI32), myelin basic protein (MBP), and reactive astrocyte markers (glial fibrillary acidic protein [GFAP]) by immunofluorescence staining. Images were captured with an Olympus APX100 microscope and analyzed by CellSense and Fiji-Image J software.

Isolation of cerebral microvessels

Cortical microvessels were isolated from mouse brain cortex that yields microvessel fragments with consistent populations of endothelial cells and astrocyte end feet.18 The astrocytes attached to the microvessels were characterized by positive CD31 or aquaporin 4 staining.

In vivo cognitive assessment

The learning and memory function of the mice was assessed using the novel object recognition (NOR) tests. The data were collected at baseline and day 7 and 14 following heme challenge and analyzed using Anymaze software.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed data were analyzed using a 2-tailed, paired, or unpaired Student’s t test and 1-way analysis of variance using GraphPad Prism 10 software.

Results and discussion

Hemolysis is associated with loss of neuroaxonal integrity and Tau phosphorylation in SCD

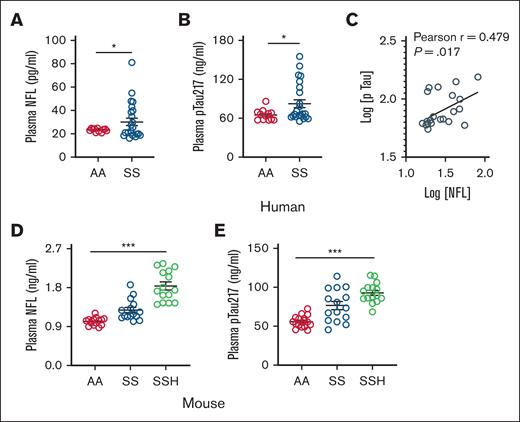

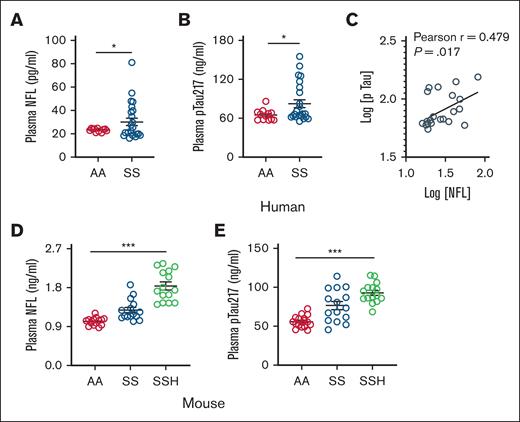

Destruction of sickle hemoglobin in the intravascular space causes elevation of hemolytic byproduct heme that promotes vasculopathy including cerebrovascular injury.19 The extracellular heme interacts with the cerebrovascular endothelium, subsequently triggering the reactivation of adjacent astrocytes. This process may lead to microstructural neuroaxonal damage and cognitive impairment. Neuroaxonal damage is correlated with the release of neurofilament light chain (NFL), and plasma levels of NFL are elevated in patients with neurodegenerative disease.20 Neuroaxonal damage is strongly associated with cognitive impairment which is correlated with elevation of circulating pTau.21,22 In a cohort of biorepository plasma, we discovered that the patients with SCD had significantly elevated levels of plasma NFL6 and pTau217 compared to nonsickle control individuals (Figure 1A-B; supplemental Table 1). Although the plasma NFL and pTau217 was strongly correlated (Figure 1C), we evaluated that each parameter was strongly associated with biomarkers of intravascular hemolysis, such as, total plasma heme and lactate dehydrogenase (supplemental Table 2). The SS mice phenocopy human SCD patients with significantly elevated NFL and pTau217 in their plasma compared to AA mice. Intravenous injection of ferric heme, simulating acute intravascular hemolysis, initially elevated plasma heme levels, which were subsequently normalized within 24 hours exclusively in SS mice, but not in AA mice (supplemental Figure 1A). Notably, heme challenge significantly augmented plasma NFL associated with simultaneous induction of plasma pTau217 in these mice (Figure 1D-E; supplemental Figure 1B). These findings suggest that mild elevation of circulating heme, induced by acute intravascular hemolysis in SCD, may initiate neuroaxonal damage.

Association of hemolytic biomarkers with elevated circulating NFL and pTau in SCD. Biorepository steady state plasma samples were analyzed for hemolytic and neurocognitive biomarkers using enzyme-linked immunosorbent or colorimetric assays following manufacturer’s instructions. (A) Level of plasma NFL is elevated in patients with SCD (SS) compared to age-matched nonsickle (AA) individuals (AA, n = 12; SS, n = 24). (B) Level of plasma pTau217 is also elevated in patients with SCD (SS) as compared to AA individuals. (C) Association of plasma NFL and pTau217 in individuals with SCD (n = 24) in logarithmic scale. (D-E) Plasma NFL and pTau217 in AA and SS mice (n = 15; M, 6; F, 9) at baseline and following heme challenge in SS mice (SSH; n = 15; M, 6; F, 9). Unpaired t test for panels A-B; 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for panels D-E. ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001. F, female mice; M, male mice.

Association of hemolytic biomarkers with elevated circulating NFL and pTau in SCD. Biorepository steady state plasma samples were analyzed for hemolytic and neurocognitive biomarkers using enzyme-linked immunosorbent or colorimetric assays following manufacturer’s instructions. (A) Level of plasma NFL is elevated in patients with SCD (SS) compared to age-matched nonsickle (AA) individuals (AA, n = 12; SS, n = 24). (B) Level of plasma pTau217 is also elevated in patients with SCD (SS) as compared to AA individuals. (C) Association of plasma NFL and pTau217 in individuals with SCD (n = 24) in logarithmic scale. (D-E) Plasma NFL and pTau217 in AA and SS mice (n = 15; M, 6; F, 9) at baseline and following heme challenge in SS mice (SSH; n = 15; M, 6; F, 9). Unpaired t test for panels A-B; 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for panels D-E. ∗P < .05, ∗∗∗P < .001. F, female mice; M, male mice.

Elevated circulating heme drives neuroaxonal damage and poor cognitive response in SS mice

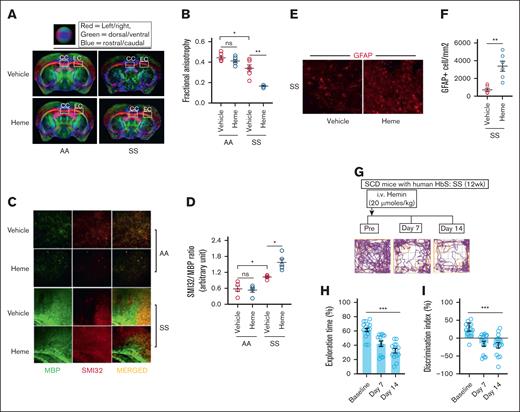

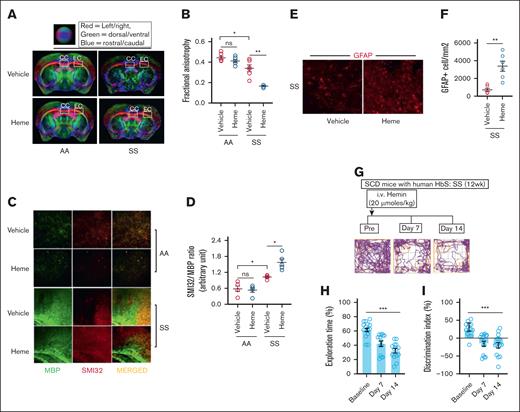

We have previously reported that (1) the microstructural damage identified by DTI and (2 the SMI32/MBP ratio, a histological indicator of neuroaxonal damage, are significantly higher in the SS mice compared to AA mice.6 In this study, data from DTI were analyzed to assess FA, a marker of axonal tissue damage based on water diffusion directionality, in the corpus callosum and external capsule regions. The SS mice subjected to heme challenge exhibited significantly lower FA values compared to the vehicle-injected mice. Notably, heme challenge did not induce any alterations in FA levels in AA mice, suggesting that the effects of elevated heme are exclusive to SS mice (Figure 2A-B). Moreover, to determine heme as a critical driver altering the microstructural architecture in SS, we pretreated the SS mice with hemopexin, the high affinity heme scavenger, prior to heme injection in the SS mice. The effect on FA disappeared in the hemopexin-treated SS mice following heme challenge (supplemental Figure 2A-B). We then investigated whether the noninvasive DTI findings were corroborated with SMI32/MBP ratio in heme-induced SS mice. The SMI32/MBP relative staining intensity was significantly higher in heme-induced SS mice, whereas the AA mice challenged with heme had no effect on SMI32/MBP ratio (Figure 2C-D).

Heme-induced microstructural neuroaxonal damage is associated with poor cognitive responses in SCD mice. (A-B) Representative DTI image from AA and SS mice challenged with vehicle or heme and quantitation of FA (n = 6; M, 3; F, 3). (C-D) Elevated SMI32 accumulation compared to MBP and quantitation of staining intensity (SMI32/MBP ratio) indicating increased white matter injury in the SS mice at 24 hours following heme challenge (n = 5; M, 3; F, 2; original magnification ×20). (E-F) Representative photomicrograph and quantitation of GFAP-positive (GFAP+) astrocytes in cerebral tissue sections from SS and SSH mice (original magnification ×20; n = 6; M, 4; F, 2). (G-I) The SS mice were subjected to NOR testing at baseline followed by 7-days and 14-days post-heme challenges in a longitudinal fashion (n = 14; M, 8; F, 6). (G) Representative track plot from NOR testing showing halted movement of SS mice at day 7 and 14 following heme challenge compared to their baseline movement. (H-I) Memory and learning behavioral parameters including the exploration time (H), discrimination index (I) during NOR testing in the SS mice prior to and following heme injection indicating poor cognitive responses following heme challenge. Unpaired t test for panels B,D,F; 1-way ANOVA for panels H-I. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. F, female mice; M, male mice; ns, not significant.

Heme-induced microstructural neuroaxonal damage is associated with poor cognitive responses in SCD mice. (A-B) Representative DTI image from AA and SS mice challenged with vehicle or heme and quantitation of FA (n = 6; M, 3; F, 3). (C-D) Elevated SMI32 accumulation compared to MBP and quantitation of staining intensity (SMI32/MBP ratio) indicating increased white matter injury in the SS mice at 24 hours following heme challenge (n = 5; M, 3; F, 2; original magnification ×20). (E-F) Representative photomicrograph and quantitation of GFAP-positive (GFAP+) astrocytes in cerebral tissue sections from SS and SSH mice (original magnification ×20; n = 6; M, 4; F, 2). (G-I) The SS mice were subjected to NOR testing at baseline followed by 7-days and 14-days post-heme challenges in a longitudinal fashion (n = 14; M, 8; F, 6). (G) Representative track plot from NOR testing showing halted movement of SS mice at day 7 and 14 following heme challenge compared to their baseline movement. (H-I) Memory and learning behavioral parameters including the exploration time (H), discrimination index (I) during NOR testing in the SS mice prior to and following heme injection indicating poor cognitive responses following heme challenge. Unpaired t test for panels B,D,F; 1-way ANOVA for panels H-I. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. F, female mice; M, male mice; ns, not significant.

Astrocytes serve as the interface between circulating heme and neurons in the brain and we have previously reported that cerebral microstructural damage in SS mice was associated with elevated astrocyte reactivity.6 We found a higher number of GFAP-positive reactive astrocytes in the brain from the heme-challenged SS mice (Figure 2E-F).

Several studies have identified poor cognitive function among patients with SCD associated with neuroaxonal damage.3,23 We have shown that the SS mice have poor cognitive response compared to AA control mice in NOR testing.6 We then tested the effect of extracellular circulating heme on cognitive responses in heme-challenged SS mice. The NOR testing demonstrated interruptions of movement in SS mice at day 7 and 14 following heme challenge, in contrast to their baseline movement patterns (Figure 2G). We found that (1) the percent exploration time, indicating the time spent exploring the novel object in NOR testing, and (2) the discrimination index identifying the difference between the time spent exploring the familial object vs the new object were significantly lower in the SS mice following heme challenge compared to their baseline (Figure 2H-I). Ex-vivo DTI imaging and immunofluorescence staining conducted after 14 days of heme challenge revealed a FA and SMI32/MBP ratio comparable to those observed in SS mice following 24 hours of heme injection (supplemental Figure 3). These findings indicate that the heme-induced cerebral microstructural damage persisted for 2 weeks, potentially contributing to the progressive cognitive decline observed in SS mice.

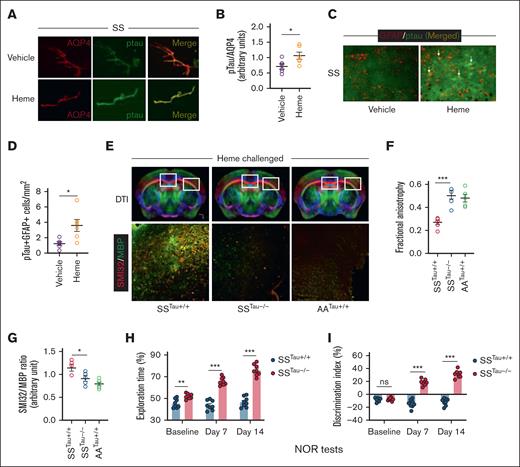

Tau phosphorylation is critical for neuroaxonal damage and cognitive impairment in SCD mice

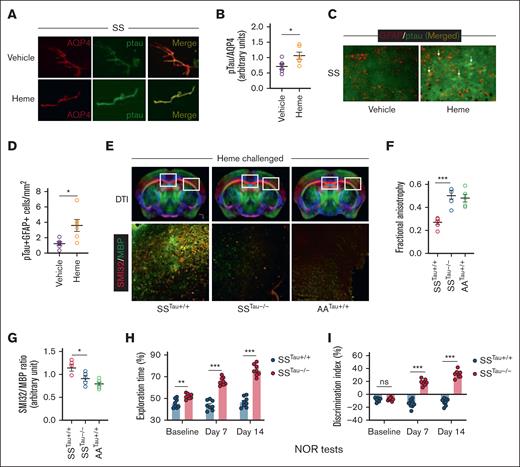

We then tested whether elevated circulating heme induces Tau phosphorylation in the cerebrovascular endothelium of the SS mice. Immunofluorescence staining in the cerebral microvessels isolated from heme-challenged SS mouse brains showed elevated pTau expression in the microvascular endothelium adjacent to the astrocytes (Figure 3A-B; supplemental Figure 4). Interestingly, pTau was co-expressed with GFAP+ astrocytes within heme-challenged SS mouse brains (Figure 3C-D). To test the specific role of pTau in neuroaxonal damage and cognitive impairment in the SS mice, we generated a new sickle bone marrow chimera strain by transplanting the bone marrow from donor SS mice to recipient Tau˗/˗ mice with global deficiency of Tau expression and wild-type B6 mice (Tau+/+). The novel sickle bone marrow chimera mice (SSTau˗/˗ and SSTau+/+) have SCD hematological phenotypes with deficiency (SSTau˗/˗) or expression (SSTau+/+) of Tau in nonhematopoietic tissues (supplemental Figure 5). A chimera strain generated by transplanting AA bone marrow to Tau+/+ mice (AATau+/+) was used as radiation control. Following heme challenge, the SSTau˗/˗ mice had reduced microstructural cerebral tissue damage with improved neuroaxonal integrity as evidenced from elevated FA and reduced SMI32/MBP ratio in the SSTau˗/˗ mice compared to the SSTau+/+ mice. Interestingly, presence of Tau does not seem to influence the microstructural architecture of the brain in absence of SCD genotypes. The AATau+/+ mice did not show any changes in their FA or SMI32/MBP values following heme challenge (Figure 3E-G). The absence of Tau resulted in enhanced cognitive responses in NOR testing. The SSTau˗/˗ mice exhibited significant improvement, characterized by increased exploration time and a higher discrimination index, in comparison to the SSTau+/+ mice at baseline and following heme challenge (Figure 3H-I).

The critical involvement of Tau in the heme-mediated neurocognitive responses in SCD mice. (A-B) Representative photomicrograph and relative fluorescence intensity for the expression of pTau in the isolated cerebral microvessels from vehicle (SS) and heme (SSH) injected SCD mice showing coexpression of pTau and aquaporin 4 (AQP4), marker for astrocytes adjacent to cerebral microvascular endothelium (original magnification ×20). (C-D) Representative photomicrograph and fluorescence intensity quantitation showing expression of pTau in heme-induced SS mice associated with GFAP+ reactive astrocytes. Arrows indicate coexpression of GFAP and pTau in some astrocytes (original magnification ×20). (n = 6; M, 3; F, 3). (E-G) Sickle bone marrow chimera mice with (SSTau+/+) or without (SSTau˗/˗) Tau deficiency in nonhematopoietic tissues, and control (AA) bone marrow transplanted Tau+/+ mice (AATau+/+) were challenged with heme and tested for neuroaxonal damage. Representative images showing DTI scans and SMI32/MBP expression within the indicated regions of corpus callosum and external capsule (original magnification ×20) from heme injected SSTau+/+, SSTau˗/˗ and AATau+/+ mice (E), quantitation of FA (F), and SMI32/MBP intensity (G) demonstrating reduced neuroaxonal damage in absence of Tau (n = 6; M, 3; F, 3). (H-I) Improved exploration time (H) and discrimination index (I) in SSTau˗/˗ mice compared to SSTau+/+ mice (n = 8; M, 3; F, 5) observed during NOR testing at baseline, day 7, and day 14 following heme challenge. Unpaired t test between the indicated experimental groups. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. M, male mice; F, female mice; ns, not significant.

The critical involvement of Tau in the heme-mediated neurocognitive responses in SCD mice. (A-B) Representative photomicrograph and relative fluorescence intensity for the expression of pTau in the isolated cerebral microvessels from vehicle (SS) and heme (SSH) injected SCD mice showing coexpression of pTau and aquaporin 4 (AQP4), marker for astrocytes adjacent to cerebral microvascular endothelium (original magnification ×20). (C-D) Representative photomicrograph and fluorescence intensity quantitation showing expression of pTau in heme-induced SS mice associated with GFAP+ reactive astrocytes. Arrows indicate coexpression of GFAP and pTau in some astrocytes (original magnification ×20). (n = 6; M, 3; F, 3). (E-G) Sickle bone marrow chimera mice with (SSTau+/+) or without (SSTau˗/˗) Tau deficiency in nonhematopoietic tissues, and control (AA) bone marrow transplanted Tau+/+ mice (AATau+/+) were challenged with heme and tested for neuroaxonal damage. Representative images showing DTI scans and SMI32/MBP expression within the indicated regions of corpus callosum and external capsule (original magnification ×20) from heme injected SSTau+/+, SSTau˗/˗ and AATau+/+ mice (E), quantitation of FA (F), and SMI32/MBP intensity (G) demonstrating reduced neuroaxonal damage in absence of Tau (n = 6; M, 3; F, 3). (H-I) Improved exploration time (H) and discrimination index (I) in SSTau˗/˗ mice compared to SSTau+/+ mice (n = 8; M, 3; F, 5) observed during NOR testing at baseline, day 7, and day 14 following heme challenge. Unpaired t test between the indicated experimental groups. ∗P < .05, ∗∗P < .01, ∗∗∗P < .001. M, male mice; F, female mice; ns, not significant.

In summary, we discovered that extracellular heme plays an important role in the cerebrovascular complications of SCD and identified Tau as a targetable molecular intermediate.

The de novo synthesis of pTau within the cerebrovascular coupling unit may drive microstructural neuroaxonal damage that leads to cognitive deficiencies. It is plausible that high hemopexin levels in AATau+/+ mice may scavenge excess circulating heme, thereby mitigating its impact on Tau phosphorylation. Conversely, in SS mice, the absence of hemopexin facilitates the exposure of excess heme to the cerebral microvasculature and adjacent astrocytes, ultimately inducing Tau phosphorylation. Inhibition of Tau phosphorylation may be a potential therapeutic strategy to prevent neurocognitive deterioration in SCD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grant 1R21NS131634-01A1 (R.H.); NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants R01DK124426 (S.G.) and R01DK132145 (S.G.); and a P3HVB grant from the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania and Vitalant (R.H.). This work used the Advanced Imaging Center (RRID:SCR_025139), a core research facility partially supported by the University of Pittsburgh and the office of the Senior Vice Chancellor for Health Sciences.

Authorship

Contribution: X.H. interpreted cognitive data and reviewed the manuscript; S.C.L. generated the targeted Tau-knockout mice and performed the bone marrow transplantation experiments; N.S. performed the immunofluorescence staining; L.M.F. and T.K.H. performed, analyzed, and interpreted diffusion tensor imaging data; P.M. performed ELISA experiments; A.E.A. organized the clinical samples and revised the manuscript; H.W. conducted statistical analysis; S.G. reviewed the manuscript; E.M.N. provided the clinical samples and critically reviewed and edited the manuscript; and R.H. conceived and designed the study, performed experiments, analyzed and interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript with consultation and contribution from the coauthors.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Rimi Hazra, Division of Classical Hematology, Vascular Medicine Institute, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, BST-E1200-23B, 200 Lothrop Street, Pittsburgh, PA 15261; email: rih17@pitt.edu.

References

Author notes

Original data are available from the corresponding author, Rimi Hazra (rih17@pitt.edu), on request.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.