In this issue of Blood Red Cells & Iron, Tsuboi et al1 describe the identification and development of a new peptide inhibitor that effectively neutralizes hepcidin and restores cellular iron efflux through ferroportin. Therapeutic administration of this inhibitor in mice prevented hepcidin-induced hypoferremia and ameliorated anemia associated with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Hepcidin is a liver-derived peptide hormone that regulates dietary iron absorption and systemic iron traffic.2 It binds to the iron exporter ferroportin on target cells (including duodenal enterocytes, tissue macrophages, and hepatocytes), thereby inactivating it. Hepcidin binding physically blocks the iron efflux pathway3 and subsequently triggers ferroportin ubiquitination and degradation.4 Hepcidin expression is transcriptionally upregulated in response to increased iron levels or inflammation. Iron-induced hepcidin activation maintains systemic homeostasis and prevents iron overload, whereas inflammation-driven hepcidin production causes hypoferremia, likely as part of an innate immune defense that limits iron availability to invading pathogens.

Under normal conditions, hepcidin expression returns to baseline once inflammation resolves. However, during chronic inflammatory states, persistent hepcidin overproduction and the ensuing hypoferremia restrict iron delivery to the bone marrow, thereby impairing erythropoiesis. This maladaptive response underlies the anemia of inflammation, also known as anemia of chronic disease, characterized by iron sequestration within macrophages, hypoferremia, hyperferritinemia, impaired erythropoiesis, and shortened red blood cell life span.5 Similar features define anemia associated with CKD, in which elevated circulating hepcidin reflects both inflammation-driven transcriptional activation and reduced renal clearance of the hormone.

Anemia is a major predictor of mortality and cardiovascular complications in patients with CKD, underscoring the importance of its effective management.6 Current therapeutic strategies typically involve iron supplementation, often combined with erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESA). However, elevated hepcidin levels in CKD impair iron mobilization and utilization, whereas ESA can be associated with cardiovascular adverse effects. Consequently, there remains an unmet clinical need for safer and more effective treatments for CKD-associated anemia. Targeting hepcidin has therefore emerged as a promising therapeutic approach.7 Several hepcidin-suppressing strategies are under preclinical and clinical evaluation, including neutralizing antibodies and small molecule inhibitors directed against components of hepcidin signaling pathways.8

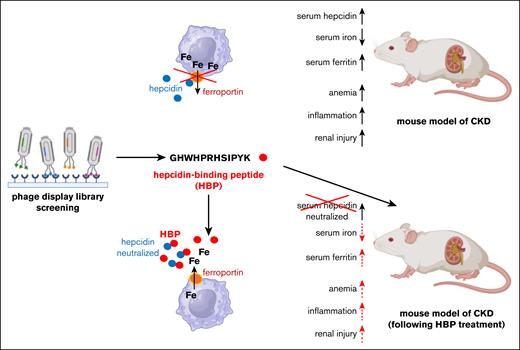

By screening a phage display library, Tsuboi et al identified a hepcidin-binding peptide (HBP; GHWHPRHSIPYK) that lacks secondary structure and shows no homology to known protein domains. The poly(ethylene glycol)–conjugated HBP exhibited high binding affinity for hepcidin (KD = 1.2 × 10˗8 M), exceeding that of hepcidin for ferroportin (KD = 10 × 10˗8 M). Consistent with this, treatment with excess HBP, but not a scrambled control peptide, prevented hepcidin-induced internalization and degradation of a ferroportin-EGFP reporter in transfected COS-1 and HEK293 cells. Likewise, HBP blocked hepcidin-induced iron retention in HepG2 cells expressing endogenous ferroportin and in ferroportin-EGFP transfected COS-1 cells. In vivo, although hepcidin injection caused hypoferremia in C57/BL6J mice, coinjection of HBP effectively abrogated this response, demonstrating functional inhibition of hepcidin activity.

Tsuboi et al next evaluated the pharmacological efficacy of HBP in a mouse model of adenine-induced CKD and associated anemia. This model is characterized by renal fibrosis and elevated markers of kidney injury, including blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and inorganic phosphorous, and renal Col1a1 expression, along with systemic inflammation indicated by high plasma C-reactive protein and renal Il6 expression. These pathological changes are accompanied by hyperhepcidinemia, hypoferremia, hyperferritinemia, and reduced red blood cell count, hemoglobin, and hematocrit. Therapeutic administration of HBP improved renal pathology, normalized markers of kidney injury and inflammation, and restored plasma iron and ferritin levels by neutralizing hepcidin activity without altering its concentration (see figure). Importantly, HBP treatment also alleviated anemia in this model. Together, these results highlight HBP as a promising therapeutic strategy for hepcidin-mediated anemia in CKD and are supportive to recent observations that iron deficiency aggravates CKD-related complications such as renal fibrosis and inflammation.9

HBP, identified by screening of a phage display library, neutralizes hepcidin, restores iron efflux through ferroportin and ameliorates anemia, inflammation, and renal pathology in a mouse model of CKD.

HBP, identified by screening of a phage display library, neutralizes hepcidin, restores iron efflux through ferroportin and ameliorates anemia, inflammation, and renal pathology in a mouse model of CKD.

Given that excessive hepcidin expression is a key driver of anemia in CKD and other chronic inflammatory disorders, hepcidin-lowering strategies have attracted considerable interest for their translational potential. Antibodies targeting hemojuvelin (DISC-0974) or BMP6 (LY3113593) suppress hepcidin transcription by disrupting upstream signaling.8 Prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors such as roxadustat, daprodustat, and vadadustat stabilize hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF) and stimulate erythropoiesis in CKD by inducing transcription of erythropoietin (EPO), a HIF2α target gene. Among downstream targets of EPO, erythroferrone acts as a physiological hepcidin suppressor. Although prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors appear to improve hemoglobinization and iron utilization compared with ESA, they have not achieved meaningful reduction in cardiovascular adverse events,10 possibly due to pleiotropic effects of the drugs.

It should also be noted that several direct hepcidin-binding molecules have been developed, including the engineered anticalin protein PRS-080#22, the Spiegelmer NOX/H94 (Lexapeptid), and the hepcidin-neutralizing antibody LY2787106.8 Compared with these modalities, HBP employs a similar neutralization mechanism but within a small-peptide framework that may offer advantages in manufacturability, tissue penetration, and potentially lower immunogenicity. Although the study by Tsuboi et al highlights the translational promise of HBP, further optimization and comparative evaluation will be required to establish pharmacological or safety benefits over existing biologics. A comprehensive biochemical and pharmacological characterization is also needed to confirm HBP’s specificity for hepcidin, exclude off-target interactions, and define its pharmacokinetic and immunogenic properties. Additional validation in preclinical models will be essential to evaluate efficacy, safety, and dosing before progression to clinical trials.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.