Mass spectrometry (MS) is an emerging tool in multiple myeloma that detects and quantifies monoclonal proteins in the peripheral blood with sensitivity several orders of magnitude greater than conventional serum protein electrophoresis and immunofixation. Both intact light-chain (top-down) and clonotypic peptide (bottom-up) MS approaches have demonstrated sensitivity comparable to, or even surpassing, bone marrow (BM)–based assessments using next-generation flow cytometry or sequencing. However, due to the delayed clearance of paraproteins, MS may be less informative for early response assessment, underscoring the need to define the optimal timing for evaluation. MS assays have now transitioned from research settings to commercial availability, addressing the clinical demand for sensitive, noninvasive monitoring tools that avoid reliance on BM biopsies. This review provides an overview of MS and explores its growing role in clinical practice.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignant plasma cell disorder that is uniquely defined and evaluated by its production of a monoclonal protein detectable in the serum and/or urine. With advances in MM therapies, patients are now routinely achieving unprecedented depths of response that have outpaced traditional methods of quantifying treatment effect. To better assess efficacy, more sensitive tools have emerged, beginning with minimal (or measurable) residual disease (MRD) testing of bone marrow (BM) aspirates by next-generation sequencing (NGS) and next-generation flow cytometry (NGF) and, now, mass spectrometry (MS) in the peripheral blood (PB). This review explores the emerging promise of MRD testing by MS, including technical principles and its clinical relevance.

BM assessments of MRD

Depth of response in myeloma has long been associated with outcomes in MM, starting with traditional criteria of complete response (CR) in both younger transplant-eligible patients1,2 and older patients not eligible for more intensive therapy.3 Introduction of higher sensitivity testing by NGS and NGF has built on these findings, rendering conventional response definitions less informative.4 The clonoSEQ assay (Adaptive Biotechnologies) can detect disease at a threshold of 1 in 106 cells using NGS5 and 2 × 10–6 using NGF.6 The International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG)7 and Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network8 have provided guidance on definitions of MRD, with the IMWG recommending a sensitivity of 10−5.

Several meta-analyses have consistently shown that depth of response by MRD, beyond CR, is essential and correlates with improvement in overall survival (OS).9-11 Updated analyses by the EVIDENCE12 and i2TEAMM13 (International Independent Team for Endpoint Approval of Myeloma Minimal Residual Disease) focused on data in randomized trials and showed that MRD at 10−5 at a time point of 9 to 12 months strongly correlated with progression-free survival (PFS). On the basis of these findings, the US Food and Drug Administration Oncology Drug Advisory Committee voted unanimously in April 2024 that MRD could be used as an end point for accelerated approval in MM.14 Increasingly, MRD is incorporated as an end point in several large phase 3 trials.15-17

Deeper responses beyond 10−5 are associated with even better outcomes. In the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome (IFM) 2009 study of up-front vs deferred autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT), MRD negativity at 10−6 by NGS18 was correlated with superior PFS and OS. Moreover, each log improvement in response was tied to gains in PFS. This concept, though preliminary, was extended further at the 10−7 level in the MRD2STOP trial.19 Finally, sustained MRD negativity (defined by the IMWG as 2 consecutive MRD-negative results at least 1 year apart)7 is increasingly recognized to offer even better prognostication compared with MRD negativity at a single time point.20-22

However, despite the precision offered by BM-based MRD testing, it comes with several drawbacks (Table 1). The most obvious barrier is that it is an invasive procedure that depends on patient cooperation and willingness. This imposes a ceiling on how frequently BM aspirations can be performed. From a disease standpoint, BM involvement by MM may be patchy or not present at all, as in the case of macrofocal disease.23-25 Analysis of the PB provides a systemic assessment and may avoid the pitfalls of false negatives in, for example, patients with extramedullary disease.26

Comparison of MRD assessments by BM vs PB MS

| . | BM aspirate for MRD . | PB for MS MRD . |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Well established, standardized, and validated | Not invasive Patient preference Allows for more frequent and dynamic monitoring |

| Disadvantages | Invasive, limited by patient tolerability Hemodilution may affect sensitivity Cannot assess for extramedullary disease Limited by patchy BM involvement | Half-life of IgG (∼23 days) and IgA (4-7 days) may lead to false “positive” MRD assessment; half-life even longer with smaller concentrations Not useful in nonsecretory disease For clonotypic MS, requires a baseline sample to enable tracking |

| . | BM aspirate for MRD . | PB for MS MRD . |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Well established, standardized, and validated | Not invasive Patient preference Allows for more frequent and dynamic monitoring |

| Disadvantages | Invasive, limited by patient tolerability Hemodilution may affect sensitivity Cannot assess for extramedullary disease Limited by patchy BM involvement | Half-life of IgG (∼23 days) and IgA (4-7 days) may lead to false “positive” MRD assessment; half-life even longer with smaller concentrations Not useful in nonsecretory disease For clonotypic MS, requires a baseline sample to enable tracking |

PB assessments of MRD

The limitations of BM biopsies have motivated development of “liquid biopsies,” which use the same tools with those on the PB, such as by NGF27 or NGS,28 or newer methodologies such as circulating free tumor DNA29 or whole-genome low-pass sequencing.30 These assays, however, may be constrained by the low level of circulating MM cells31,32 or DNA33,34 in the PB; thus, they do not currently surpass the sensitivity of BM-based assays. Alternatively, paraproteins in MM could be leveraged as an MRD assay if there was an adequately sensitive test, and indeed, MS has the performance to meet this challenge.

Historically, serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) has been used to routinely detect and follow monoclonal proteins. This methodology relies on the principle that monoclonal proteins have unique properties that allow them to be separated from other antibodies secreted by normal plasma cells using agarose gels or capillary electrophoresis. SPEP has a sensitivity of 0.1 g/dL, and this improves to 0.01 g/dL with immunofixation (IFX).35 For patients with light-chain MM, in whom the amount of circulating monoclonal light chain may be below the sensitivity of SPEP/IFX, the serum free light-chain test has become an essential tool for evaluating these patients in the past 2 decades.36

The next major advance for detecting disease is MS. MS can detect monoclonal gammopathies at an even more sensitive level and potentially fulfill the goal of frictionless, serial monitoring of disease without requiring a BM biopsy. This becomes more relevant with the importance of achieving sustained MRD, which requires frequent measurements. MRD assessment will also become increasingly important in the future, as more randomized studies using MRD-guided strategies are reported.

How MS works in MM

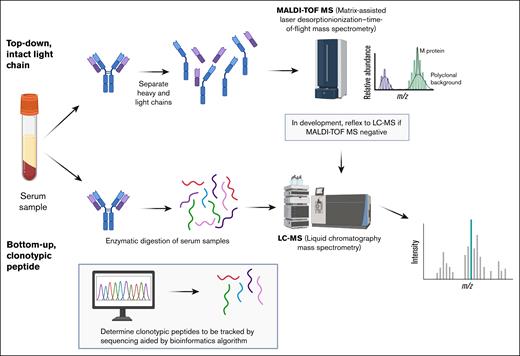

MS is a powerful tool that builds on the finding that MM cells produce homogeneous immunoglobulins with a unique amino acid sequence in the antigen-binding region, particularly within the complementarity-determining regions that confer antibody specificity. This, in turn, results in a distinct mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio. MS is widely used clinically in diverse applications to measure smaller molecules (eg, monitoring drug levels, screening newborns for metabolic disorders).37 In plasma cell disorders, MS already has an established role for subtyping amyloid protein and confirming light-chain (AL) amyloidosis.38 With improvements in technology, MS has now been applied to MM, with its more complicated proteins, to increase sensitivity by several orders of magnitude than SPEP/IFX.39 Its application in clinical trials has accelerated in recent years, and it is now commercially available. This overview builds on previous reviews40,41 to provide an update on findings from clinical trials, highlight advantages and limitations, and provide insight into future directions. Broadly speaking, there are 2 approaches: (1) the intact light-chain method (top-down) and (2) the clonotypic peptide method (bottom-up), each with its own strengths and challenges (Figure 1).

MS methods for measuring monoclonal protein. There are 2 types of MS methods in clinical use. The top-down, intact light-chain approach uses, for example, MALDI to prepare the sample for MS analysis and then relies on the monoclonal protein’s unique m/z ratio to distinguish itself from the polyclonal background. Examples include Mass-Fix and Exent. To increase sensitivity, samples that initially test negative can then be directed to LC-MS; this is under evaluation on a research basis. In the bottom-up, clonotypic approach, the monoclonal protein is digested and a unique clonotypic sequence then determined to use for tracking the monoclonal protein. This method is more sensitive than the top-down approach but has a slower turnaround time and requires a baseline sample for the sequence to track. The EasyM and M-Insight assays use the clonotypic approach.

MS methods for measuring monoclonal protein. There are 2 types of MS methods in clinical use. The top-down, intact light-chain approach uses, for example, MALDI to prepare the sample for MS analysis and then relies on the monoclonal protein’s unique m/z ratio to distinguish itself from the polyclonal background. Examples include Mass-Fix and Exent. To increase sensitivity, samples that initially test negative can then be directed to LC-MS; this is under evaluation on a research basis. In the bottom-up, clonotypic approach, the monoclonal protein is digested and a unique clonotypic sequence then determined to use for tracking the monoclonal protein. This method is more sensitive than the top-down approach but has a slower turnaround time and requires a baseline sample for the sequence to track. The EasyM and M-Insight assays use the clonotypic approach.

Top-down, intact light-chain method

With the intact light-chain method, the intact immunoglobulin light chains are analyzed based on their unique m/z ratios, which produce a distinct signature that appears as an abnormal peak above the polyclonal background. This was initially described in 2014,39 and current iterations involve purifying immunoglobulins by targeting isotype-specific combinations (ie, immunoglobulin G [IgG], IgA, IgM, κ, λ). The purified proteins are then separated using matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI) to prepare the sample for time-of-flight (TOF) MS analysis.42,43 MALDI-TOF offers high throughput, making it suitable for routine clinical use. The Mayo Clinic has developed and commercialized an automated MALDI-TOF–based assay known as Mass-Fix, which is now available to order as a standard test. With a reported sensitivity of <0.01 g/dL, Mass-Fix outperformed conventional SPEP and IFX.42 Consequently, in 2018, the Mayo Clinic transitioned from using traditional SPEP/IFX to Mass-Fix as their standard screening method for plasma cell disorders, citing a 30% improvement in efficiency.44

Another assay using a similar top-down MS approach is the Exent assay (formerly known as quantitative immunoprecipitation [QIP]–MS). Exent was launched in Europe in August 2023.45 Compared with Mass-Fix that uses nanobodies, Exent uses polyclonal sheep antibodies directed against heavy and light chains that are covalently linked to paramagnetic beads. Exent offers a sensitivity of 0.0015 g/dL.46

Instead of MALDI, liquid chromatography (LC) can be used to separate intact immunoglobulins before entering the mass spectrometer. Before the development of MALDI, early forms of top-down MS used LC-MS, and one example of this later became known as miRAMM (monoclonal immunoglobulin rapid accurate mass measurement).47 LC-MS provides higher resolution but is more labor intensive than MALDI-TOF, making it less practical for high-throughput clinical testing. However, LC-MS can be used reflexively after Exent for negative samples to provide greater sensitivity, improving it to 0.0001 g/dL.48

Finally, another top-down assay in development focuses only on the free light chains themselves.49 The Mass-Fix and Exent assays use both the light chain bound to the heavy chain and the free light chain. Because the free light chains have a shorter half-life, one potential benefit of this type of assay is that it may be affected less by delay in clearance of the monoclonal protein.

A notable advantage of MALDI-MS–based assays is that they do not require a baseline to determine the m/z peak to follow; this assay only requires the peak to stand out from the polyclonal background. Nevertheless, knowledge of this baseline peak will improve the sensitivity in lower disease burden states where the polyclonal background may cause some interference.

Bottom-up, clonotypic method

The clonotypic peptide or bottom-up approach is a different MS strategy that arrived after the top-down approach and offers greater sensitivity, though it is more complex and has a slower turnaround time. This technique begins by identifying a unique peptide sequence derived from the patient’s monoclonal protein, either directly from digested serum protein using MS50,51 or indirectly by sequencing RNA of the MM cells.52 This has parallels with how MRD assessment by NGS requires an “ID” sample to inform which sequence to track. Once identified, the assay can monitor the clonotypic peptide with high sensitivity, independent of background polyclonal immunoglobulins. This overcomes a key limitation of top-down approaches, in which the polyclonal background can reduce sensitivity.

There are 2 commercially available clonotypic tests, EasyM (Rapid Novor)53 and M-Insight (Sebia),54 with sensitivities of 5.8 × 10−5 g/dL and 1 × 10−5 g/dL, respectively. The sensitivity may further vary based on the nature of the clonotypic peptide itself. In a more recent study of EasyM,55 the limit of detection (LoD) varied from 1.5 × 10−5 to 3.2 × 10−3 g/dL. Overall, these tests are upwards of 1000 times more sensitive than SPEP/IFX, raising the possibility that these assays can replace BM MRD for disease assessment.

However, the increased sensitivity afforded by knowledge of the monoclonal protein sequence can also be a limitation. The clonotypic approach requires a baseline serum sample for sequencing with a monoclonal protein of generally at least 0.2 g/dL or serum free light chain of 20 to 40 mg/dL. This means that this sample needs to be collected around the time of diagnosis, before treatment, or early on in treatment. Thus, for the patient in CR in whom the question of MRD is being raised, the clonotypic MS approach is not feasible as this previous serum sample with sufficient monoclonal protein to use51 for determining the clonotypic sequence is generally not available outside of research settings in which samples were prospectively stored. Given the superior sensitivity of MS, it is increasingly important to determine the most informative thresholds to use for monoclonal protein concentrations for assessing prognosis.

Use cases for MS in MM

Prognostication

With the increased sensitivity of MS over SPEP/IFX, the question arises of whether MS can achieve superior prognostication than conventional IMWG responses and how it compares with BM MRD assays. The following summarizes the data from clinical trials, mainly in newly diagnosed patients.

Top-down approach

COMPARED WITH SPEP/IFX

Several studies have demonstrated the prognostic significance of MS. Focusing first on top-down MALDI-MS methods, such as Mass-Fix, QIP-MS (a precursor of Exent), and Exent, it is well established that MALDI-MS can detect paraprotein in many cases in which SPEP/IFX cannot (Table 2).56-66 This translates into better prognostication with MS. For example, in the STaMINA trial, Mass-Fix outperformed SPEP/IFX and CR status for predicting PFS and OS.56 In a substudy of the Spanish PETHEMA/GEM2012MENOS65 trial in newly diagnosed MM, the Exent assay more accurately predicted PFS than SPEP/IFX.57 This was particularly true in later time points compared with after induction, suggesting that the prognostic significance of MS increases over time. In the ATLAS trial, which studied different maintenance strategies post-ASCT, Exent status further stratified PFS in patients in CR.60 A post hoc analysis of the GMMG-MM5 study in newly diagnosed MM found Exent to be independently prognostic even when accounting for established high-risk disease markers and CR status.59 Using LC-MS further increases the sensitivity of the top-down approach, and samples that test negative initially by Exent can be reflexed to LC-MS.48,62,66,67

MS assays for measuring PB MRD

| Assay . | Type . | Platform . | Sensitivity∗ . | Examples of trials in which assay has been used . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass-Fix (Mayo Clinic) | Intact light chain | MALDI-TOF | <0.01 g/dL42 | STaMINA56 | Commercially available through Mayo Clinic reference laboratory; has replaced SPEP/IFX in their workflow42,43 |

| Exent (Thermo Fisher, previously known as QIP-MS) | Intact light chain | MALDI-TOF | 0.0015 g/dL46 | GEM2012MENOS65,57,58 GMMG-MM5,59 ATLAS,60 GEM-CESAR,61 and Derman et al62 | Can be automated for high throughput Platform commercially available in Europe; availability in the United States pending |

| LC-MS | Intact light chain | LC-MS | 0.0001 g/dL48 | Can reflex off of Exent-negative samples Not commercially available | |

| EasyM (Rapid Novor) | Clonotypic peptide | LC-MS | 5.8 × 10−5 g/dL53 | MCRN-001,53 MM19, and MM2168 | Commercially available in the United States |

| M-Insight (Sebia) | Clonotypic peptide | LC-MS | 1 × 10−5 g/dL54 | IFM 200969,70 | Commercially available in the United States |

| Assay . | Type . | Platform . | Sensitivity∗ . | Examples of trials in which assay has been used . | Comments . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass-Fix (Mayo Clinic) | Intact light chain | MALDI-TOF | <0.01 g/dL42 | STaMINA56 | Commercially available through Mayo Clinic reference laboratory; has replaced SPEP/IFX in their workflow42,43 |

| Exent (Thermo Fisher, previously known as QIP-MS) | Intact light chain | MALDI-TOF | 0.0015 g/dL46 | GEM2012MENOS65,57,58 GMMG-MM5,59 ATLAS,60 GEM-CESAR,61 and Derman et al62 | Can be automated for high throughput Platform commercially available in Europe; availability in the United States pending |

| LC-MS | Intact light chain | LC-MS | 0.0001 g/dL48 | Can reflex off of Exent-negative samples Not commercially available | |

| EasyM (Rapid Novor) | Clonotypic peptide | LC-MS | 5.8 × 10−5 g/dL53 | MCRN-001,53 MM19, and MM2168 | Commercially available in the United States |

| M-Insight (Sebia) | Clonotypic peptide | LC-MS | 1 × 10−5 g/dL54 | IFM 200969,70 | Commercially available in the United States |

Bottom-up (clonotypic peptide) methods are generally more sensitive than top-down (intact light chain) approaches. To achieve this performance, bottom-up approaches require a baseline sample to determine the monoclonal protein sequence to follow. Top-down approaches (intact light chain) offer improved turnaround time and do not require a baseline sample. Adapted from Yee.71

For comparison, SPEP/IFX has a sensitivity of 0.01 g/dL.

COMPARED WITH BM MRD ASSAYS

To truly advance blood-based MRD diagnostics, MS must compare favorably with highly sensitive BM assays from a detection and prognostic standpoint. In particular, it is critical to understand how MS can complement BM assays, and if both pieces of data contribute to prognosis better than each individually or whether MS status is individually prognostic with a great deal of overlap with BM assays. In a phase 2 trial in newly diagnosed MM comparing MS with BM-based NGS (sensitivity up to 10−6), MALDI-MS was found to have 83% agreement with NGS, whereas there was only 63% agreement between LC-MS and NGS.66 However, the lower level of agreement is not necessarily a drawback for LC-MS. Rather, it may reflect the increased sensitivity of LC-MS, which detected cases of residual disease where NGS did not. Indeed, LC-MS was able to further stratify PFS outcomes in patients who were BM NGS negative.66 The authors concluded that MALDI-MS was at least as sensitive as BM MRD by NGS with a LoD of 10−5, whereas LC-MS was at least as sensitive as BM MRD by NGS with LoD of <10−6.

In addition, the Spanish group, when analyzing the GEM2012MENOS65 and GEM2014MAIN trials, found that QIP-MS was less sensitive than BM NGF.58 For example, QIP-MS was not able to detect paraprotein in 38.6% of patients who were positive by BM NGF at 10−4 to 10−5. Similarly, in the ATLAS study, 37% of patients who were positive by NGS were not detected by Exent.67 This suggests that MS tests based on top-down, MALDI approaches may not be sensitive enough to replace BM-based MRD determinations as a standalone test.

INTEGRATING MS WITH NGF OR NGS

Combining findings from MS with NGF or NGS can enhance prognostication. In the STaMINA trial, MALDI-MS using Mass-Fix was individually prognostic as early as postinduction, and MALDI-MS status demonstrated some complementarity with BM NGF status.56 A post hoc analysis of the ATLAS trial found that, together, combined MALDI-MS negativity with Exent and BM MRD negativity by NGF or NGS was associated with superior PFS compared with MRD negativity by only 1 modality and that 18 months post-ASCT was the optimal time point to use MALDI-MS prognostically.60 The timing may be due to confounding by delayed clearance of monoclonal protein. To that end, other smaller studies assessing MALDI-MS and/or LC-MS at earlier time points did not find an association with prognosis.62,63

The analysis with MS can also be integrated with NGF performed on the PB instead. MALDI-MS using Exent was found to be individually prognostic and complementary to PB NGF in the GEM2012MENOS65/GEM2014MAIN studies.72

The value of combining BM and PB assessments of response (either by SPEP/IFX or MS) may also depend on the patient population, that is, newly diagnosed vs relapsed disease. In newly diagnosed MM, achievement of CR did not seem to add prognostic value in patients who already were BM MRD negative.73 In contrast, in patients with relapsed disease treated with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells or bispecific antibodies, the Spanish group observed that patients who were both BM MRD negative and in CR had better outcomes than patients who were MRD negative alone.74 This has been further validated in the MS era, in which MS status with QIP-MS can further categorize outcomes in patients with BM MRD negativity after CAR T-cell therapy.75 This may reflect the detection of paraprotein from extramedullary disease, which is more common in relapsed disease.

Clonotypic approach

Clonotypic peptide sequencing, such as the EasyM and M-Insight assays, can detect paraprotein even better than top-down MS methods. Indeed, they may have the sensitivity to rival the accepted standard of MRD by NGS or NGF in BM. With the EasyM assay, in a Canadian trial of newly diagnosed patients, 89% of patients in CR had detectable paraprotein by EasyM.53 Moreover, EasyM was able to detect monoclonal protein in 81.8% of cases with NGF negativity (10−5) in the BM in a retrospective Chinese study of newly diagnosed patients.55 Finally, a study of EasyM in 2 Australian trials revealed that it was positive in 74% of newly diagnosed patients who were in CR and BM NGF negative.68 With the M-Insight assay, in a post hoc analysis of 41 patients from the IFM 2009 study, M-Insight detected MRD in 93% of samples compared with only 21% by SPEP/IFX.69 Moreover, M-Insight was able to detect monoclonal protein in 14 of 15 patients classified as MRD negative by NGS at 10−6. We await more complete data on how MRD status by EasyM and M-Insight results translate to PFS or OS outcomes.53,76,77

MS resurgence as a predictor of impending relapse

At present, there are 2 forms of progression in MM: clinical progression, which refers to new or worsening myeloma-related symptoms, and biochemical progression, which is defined by an increase in monoclonal protein levels above a certain threshold. Biochemical progression is widely accepted as criteria to change treatment or enroll patients into clinical trials. Older data suggested that the median time from biochemical to clinical progression, without changing management, was <6 months, though nearly a quarter of patients with biochemical progression did not develop clinical progression after 2 years.78,79 Another retrospective analysis found that starting second-line treatment for biochemical progression vs waiting to clinical progression led to superior OS.80

An active area of discussion is whether MRD resurgence should be used as a signal to change therapy. Previous data in the era preceding quadruplet induction therapy found that the time from BM MRD resurgence to disease progression varied from <1 year to >3 years, depending on the threshold used for MRD positivity.25,81,82 In the quadruplet era, MRD resurgence at the 10–5 level, despite restarting or changing therapy in some cases, was followed by disease progression within a median of 10.1 months.83

MS resurgence appears to carry similarly poor prognosis. In a pooled analysis of Spanish studies, conversion from MALDI-MS negativity premaintenance to MS positivity carried a median PFS of <1 year, and this pattern appeared to be worse than for patients with sustained MS positivity.58 This has been demonstrated in other MALDI-MS studies as well.59,61 Similarly, with the clonotypic M-Insight assay performed on a subset of patients on the IFM 2009 trial, M-Insight was able to detect changes in monoclonal protein levels on average 442 days earlier than conventional SPEP/IFX.69

Indeed, MS, with its sensitivity coupled with its ability to be done frequently, may provide an early window into disease progression before SPEP/IFX, without requiring a BM biopsy. The REMNANT study is an ongoing trial in Norway that may help answer the question of whether patients should be treated at time of MRD resurgence (by BM NGF) vs conventional IMWG relapse.84

MS as a marker to define cure

Whether MM is a curable disease remains an ongoing question; however, it is undeniable that some patients are in a treatment-free state without evidence of disease and may, in fact, be cured.85 Exceptional responders, referring to patients who are free of progression or death for at least 8 years, were found in 9% of patients in a Mayo Clinic analysis who received ASCT and no maintenance.86 It is expected that this fraction will only increase with quadruplet induction and consolidation strategies and newer therapies, such as CAR T-cell therapies.87,88

Multimodal MRD is an excellent method to help define the absence of disease as part of the cure definition. Combining BM methods and imaging has already demonstrated the ability to guide MRD-directed discontinuation of maintenance therapy.19,89 Moreover, the BM microenvironment may play a role in determining long-term responders, and how to incorporate evaluation of the microenvironment with MRD assessment will be important in the future.90 Could MS help contribute to the definition of cure? A recent analysis found that “double negative” status by LC-MS and BM MRD by NGS (10−6) helped identify patients with long-term disease control, ultimately serving as a potential avenue to better define cures in myeloma.91 The increased sensitivity of clonotypic peptide MS with M-Insight may also help with this role as well.92

Additional uses for MS

Standard disease monitoring

Most patients with MM will have SPEP/IFX and serum free light chains checked regularly to assess ongoing responses. Could MS replace these assays entirely? Mass-Fix has been implemented clinically for all patients at the Mayo Clinic based on how they have optimized it into their workflow.43,44 A French budget analysis found that MALDI-MS may help guide more focused use of BM MRD testing and reduce costs by reserving BM MRD testing for patients testing negative by MALDI-MS.93 Indeed, MS testing may be most useful once disease is no longer detectable by conventional methods (SPEP/IFX and serum free light chains) until it can be found that cost is lower for routine MS testing over these established approaches.

Distinguishing paraprotein from therapeutic monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies, such as daratumumab and isatuximab, have transformed the treatment of MM. However, these therapies, which are IgGκ isotype, can affect traditional IMWG response assessment for patients with MM who have an IgGκ isotype. Circulating therapeutic IgGκ monoclonal antibodies may be impossible to distinguish from the underlying MM IgGκ paraprotein, potentially leading to downgrading of responses from CR.

One workaround for anti-CD38 monoclonal antibodies is a reflex interference assay.94-96 MS though is uniquely positioned to distinguish endogenous paraprotein from therapeutic monoclonal antibodies by its ability to assign a unique molecular mass to both. MS has already demonstrated the ability to resolve endogenous paraprotein from daratumumab, isatuximab, and elotuzumab.63,97-99

The increased precision of MS can also help disambiguate findings on SPEPs. There are known mimics of monoclonal bands on SPEP, inherent to the use of electrophoresis, such as fibrinogen and transferrin. The enhanced specificity of MS avoids these pitfalls. In one case series, MS revealed that what was initially interpreted as monoclonal gammopathy was actually polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia.100 MS can also distinguish between the monoclonal protein from MM vs the oligoclonal bands that may emerge after ASCT.101

Making the nonsecretory, secretory

Approximately 2% to 3% of patients with myeloma will have no or insufficient detectable paraprotein for reliable monitoring for response, termed nonsecretory or oligosecretory disease; this percentage was higher before the advent of the serum free light-chain assay. Being able to have disease to follow facilitates tracking a patient’s response to and relapse from treatment. One analysis using MALDI-MS found that 20 of 22 patients (91%) with nonsecretory MM had detectable disease using MALDI-MS, and most patients had trackable disease over time.102 However, there are scenarios, especially as MM evolves and becomes more refractory, where the disease can become nonsecretory. BM assays will continue to be useful in these cases, though hopefully MS will make this less common. Recently, soluble B-cell maturation antigen levels have been found to be a useful biomarker for monitoring patients with oligosecretory or nonsecretory MM.103

Detection of N-glycosylation

MS can also routinely detect posttranslational modification, such as N-glycosylation of light chains.104 This is clinically relevant given the association of N-glycosylation with AL amyloidosis. In a retrospective study, 32.8% of κ light chain and 10.2% of λ light chain in patients with AL amyloidosis were found to have glycosylation on Mass-Fix.104 Moreover, N-glycosylation affects risk of progression with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance. In a retrospective study of the Olmsted monoclonal gammopathy cohort at the Mayo Clinic, patients with N-glycosylation on Mass-Fix had a hazard ratio of 10.1 for developing AL amyloidosis, and interestingly, any plasma cell disorder with a hazard ratio of 7.8, compared with patients without N-glycosylation.105 This may have practical implications for how to follow patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.

Limitations and considerations

Delayed clearance of monoclonal protein

A key limitation inherent to MRD assessments by MS is the half-life of the monoclonal protein, which can confound interpretation of MS findings. The half-life of IgG is ∼23 days106 compared with 4 to 7 days for IgA107 and hours for free light chains.108 Moreover, clearance becomes longer with decreasing concentrations of IgG monoclonal protein. The neonatal Fc receptor on endothelial cells plays an important role in IgG homeostasis. With lower levels of IgG monoclonal protein, the neonatal Fc receptor is less saturated and has more available binding capacity, leading to a higher proportion of IgG being recycled back into the circulation.109,110 The phenomenon of IgG paraprotein lagging behind tumor clearance in the BM (or elsewhere) is a known issue limiting SPEP/IFX interpretation. Using even more sensitive assays such as MS only magnifies this issue.65 For example, daratumumab could be detected by Mass-Fix up to a median of 5.1 months from discontinuation.111 Consequently, patients who have cleared the BM of disease with effective therapy, such as CAR T-cell therapy, and hence MRD negative by NGS may continue to have persistent monoclonal protein detectable by MS112 and thus be categorized as “positive” by MS (and lead to downgrading of responses). This likely explains why the prognostic utility of MS improves with time.

Overall, the optimal time point for MS testing is an ongoing question. It is likely that the time point differs based on the involved isotype, given the longer half-life of IgG compared with IgA. Some data support the prognostic capabilities of MALDI-MS status at early time points, but most studies suggest that it may take up to 18 months before MS assays can be reliably prognostic, as in the ATLAS study.60 Understanding the differences in time to MS negativity for IgG vs IgA vs light chain only MM will be essential to properly interpret MS results. Furthermore, the interplay between concentration cutoffs vs percent reduction in monoclonal protein and outcomes will be important to address in future studies.

Need for baseline sample

Although the clonotypic peptide assays are the most sensitive, they require knowledge of the baseline peptide sequences to track to achieve this sensitivity. However, this baseline sample may not be available for most patients who are already diagnosed and treated and where the MRD question is now becoming germane. The top-down MALDI-MS and LC-MS assays do not require a baseline sample and thus can be more readily used in clinical practice. The sensitivity of top-down methods will improve though using a baseline sample, especially when the polyclonal background is more prominent.

Conclusions

Which MS assay is the best assay to use? The answer to this depends on the context. The clonotypic peptide assays have the highest sensitivity followed by LC-MS, provided that a baseline sample is available, with all reaching or exceeding the sensitivity of BM MRD assays. The performance of MALDI-MS assays is somewhere in between those assays and conventional SPEP/IFX, but MALDI-MS assays do not rely on a baseline sample. Ultimately, MS is one of several complementary tools available for assessing disease, with the most informative insights emerging from integration across PB, BM, and imaging modalities. MRD assessment by MS is a valuable addition as it enables more frequent, dynamic monitoring of MM without relying on BM aspirations, a change that patients welcome even more, and may be important to determine sustained MRD negativity and help guide decisions on de-escalation of treatment. Ongoing research will be critical to realize the promise of MS, determine how the cost of MS compares with other MRD assessments, and how to further incorporate MS into MM care.

Authorship

Contribution: B.A.D. and A.J.Y. wrote and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.J.Y. reports consulting for AbbVie, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Celgene, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, Karyopharm, Oncopeptides, Pfizer, Prothena, Regeneron, Sanofi, Sebia, and Takeda; and receiving research funding to institution from Amgen, BMS, GSK, Johnson & Johnson, Sanofi, and Takeda. B.A.D. reports consulting for Cota Healthcare, Canopy, Johnson & Johnson, and Sanofi; serving as an independent reviewer for clinical trial for BMS; and receiving research funding to institution from Amgen and GSK.

Correspondence: Andrew J. Yee, Center for Multiple Myeloma, Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center, 55 Fruit St, Boston, MA 02114; email: ayee1@mgh.harvard.edu.