Key Points

After weighting, a significant difference in 2-year OS but not in PFS or DOR was observed between HGBL and DLBCL.

The 2-year OS following CAR T-cell infusion (after weighted log-rank tests) remained significantly inferior for HGBL compared to DLBCL.

Visual Abstract

High-grade B-cell lymphomas (HGBL, including double-hit/triple-hit [HGBL-DH/TH], and HGBL not otherwise specified) have a poor prognosis upon failure of first-line therapy. Anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy for third-line aggressive large B-cell lymphomas (LBCL) resulted in long-term remission in ≤40% of patients. This study evaluated factors that can predict outcomes in HGBL compared to diffuse LBCL (DLBCL). We assessed the predictive value of the subtype (HGBL vs DLBCL) using weighted log-rank tests and weighted Cox models, and overall survival (OS) following CAR T-cell therapy failure. The prospective study cohort comprised 432 patients (HGBL, n = 78; DLBCL, n = 354), median follow-up of 22.8 months for HGBL and 18 months for DLBCL. Interestingly, there was no statistically significant difference in progression-free survival and OS between patients with HGBL-DH/TH lymphomas vs other high-grade histotypes. CAR T-cell therapy expansion in HGBL did not correlate with response. Before weighting, a significant difference in OS was observed between HGBL vs DLBCL (24-month OS: 37% vs 49%, P = .0036). After weighting, the difference in 2-year OS remained significant (37% vs 44%, P = .0343), and it was related to inferior survival following CAR T-cell therapy failure. The 2-year nonrelapse mortality and incidence of secondary malignancies were similar in patients with HGBL and DLBCL (11% vs 11%, P = .830; 6.4% vs 11.4%, P = .844). Among patients in whom CAR T-cell therapy failed, the 1-year OS after failure was significantly higher in transformed than de novo DLBCL and HGBL (59% vs 32% vs 11%, <0.0004). Earlier use of CAR T-cell therapy may improve the outcome of HGBL. This trial was registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov as #NCT06339255.

Introduction

High-grade B-cell lymphomas (HGBL) are a group of rare, aggressive mature B-cell lymphomas that are biologically and clinically distinct from diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and Burkitt lymphoma, accounting for ∼8% to 10% of all large B-cell lymphomas (LBCL). According to the International Consensus Classification 2022, HGBL includes lymphomas with MYC/BCL2 or MYC/BCL2/BCL6 rearrangements (HGBL-DH/TH), high-grade B-cell lymphomas not otherwise specified (HGBL-NOS, not defined by cytogenetic or molecular markers), and the provisional entity with MYC/BCL6 rearrangements.1 Intensive Burkitt-like regimens have been tested in the first line, with 4 years of progression-free survival (PFS) ranging from 50% to 65%.2,3 However, before the advent of autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, the prognosis of HGBL that was refractory or relapsed after first-line therapy was very dismal, with a 1-year PFS of 10%.4 The chemoresistance of HGBL is due to different factors, in particular genetic instability, modification of apoptotic pathways (related to overexpression of BCL2 and higher incidence of p53 mutations), and alterations in DNA repair machinery. Autologous CAR T-cell therapy targeting CD19 has shown significant efficacy in relapsed LBCL, including DLBCL, HGBL, transformed follicular lymphoma, and primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. Based on pivotal trials, 3 different CD19 CAR T-cell therapies, namely axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel), tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel), and lisocabtagene maraleucel, have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration, and European Medicines Agency for patients failing at least 2 lines of therapy.5-7 The number of patients affected by HGBL included in pivotal trials is too limited to draw conclusions about the long-term outcome of these patients. In a real-world United States study on axi-cel,8 22% of the patients were affected by HGBL, and no significant differences in 1-year overall survival (OS) were found between HGBL and non-HGBL (69% vs 68%).

The French DESCART registry recently provided a retrospective analysis, including 32% HGBL and 68% non-HGBL, and two-thirds were treated with axi-cel.9 The OS for HGBL-DH/TH was inferior to non-HGBL when evaluated from the time of eligibility to the study, likely related to a higher number of patients who never received CAR T-cell therapy infusion in the HGBL cohort for rapidly progressive disease.

Our study aimed to explore the outcomes following CAR T-cell therapy infusion in patients affected by HGBL compared to DLBCL. We used weighted comparison analyses to control confounding factors and OS following treatment failure. In addition, we explored the response to bridging therapy (BT), nonrelapse mortality (NRM), secondary primary malignancy (SPM) incidence, and CAR T-cell therapy toxicity in the 2 subtypes.

Methods

Study design and participants

CART SIE is an ongoing multicenter prospective observational study conducted across 21 Italian hematology centers (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06339255). The study includes all patients eligible for CAR T-cell therapy according to the criteria established by the European Medicines Agency and the “Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco.”

Eligible participants were adults (aged ≥18 years) affected by DLBCL, including de novo DLBCL and DLBCL arising from transformed indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), or HGBL, including HGBL-NOS, HGBL-DH/TH, and DLBCL with MYC and BCL-6 rearrangements. Patients received commercial CAR T-cell therapy as the third-line or higher treatment (September 2019 to January 2024). Histological reports and fluorescence in situ hybridization analyses were centrally collected when available. Ethical approval is described in the supplemental Methods.

Definitions and end points

The study’s primary end point was to compare the OS of patients affected by HGBL to those with DLBCL, and evaluate the OS following treatment failure. Secondary end points included assessing the response to BT, PFS, duration of response (DOR), NRM, the incidence of SPMs, and CAR T-cell toxicity in the 2 subtypes.

The definitions are given in the supplemental Methods.

Identification of CAR T-cell therapy by flow cytometry

CAR T-cell therapies were longitudinally monitored in peripheral blood through multiparameter flow cytometry using CD19 CAR detection reagent (Miltenyi), as previously described, or the CD19 CAR FMC63 Idiotype (REA1297; Miltenyi).10

Statistical analyses

The patient and tumor characteristics were summarized using the median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, and absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. The differences in characteristics between the 2 groups were expressed in standardized mean differences, which can detect group imbalances.

OS and PFS curves were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and compared between groups using the log-rank test; P values < .05 were considered significant. Univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses were applied to investigate predictive factors for OS and PFS. Results were expressed as hazard ratios (HRs) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Outcome comparison between the 2 groups was done using the stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting methodology.11 The propensity score was calculated using a multivariable logistic model estimating the probability of being in HGBL group, adjusted for age, sex, C-reactive protein (CRP) at infusion (≥10 vs <10), Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (0 vs ≥1), disease status (relapsed vs refractory), International Prognostic Index (IPI) score (0-2 vs ≥3), number of previous treatments (1-2 vs ≥3), the previous autologous stem cell transplant, response to BT (no BT vs no response vs response to BT), bulky disease, CAR T-cell therapy product (tisa-cel vs axi-cel), and vein to vein time (time from apheresis to infusion). Patients with complete data were included in the analyses. The group comparison in survival outcomes was performed using the weighted log-rank test and weighted Cox model. In contrast, the group comparison in binary outcomes was performed using the weighted logistic model.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between September 2019 and January 2024, 432 patients affected by relapsed vs refractory aggressive LBCLs received commercial CAR T-cell therapy after failing at least 2 prior lines of therapy. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristics . | HGBL (N = 78) . | DLBCL (N = 354) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | .191 | ||

| Female | 33 (42) | 120 (34) | |

| Male | 45 (58) | 234 (66) | |

| Age, median (range), y | 63 (55.5-68.0) | 60 (52.0-67-0) | .025 |

| Histology, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| HGBL-DH | 50 (64) | ||

| HGBL-NOS | 23 (30) | ||

| DLBCL MYC/BCL6 | 5 (6) | ||

| De novo | 278 (79) | ||

| Indolent transformed | 76 (21) | ||

| IPI, n (%) | .004 | ||

| 0-2 | 31 (40) | 205 (58) | |

| >2 | 47 (60) | 149 (42) | |

| LDH at infusion, n (%) | .765 | ||

| Normal | 46 (59) | 203 (57) | |

| Increased | 18 (23) | 90 (26) | |

| Missing | 14 (18) | 61 (17) | |

| CRP at infusion, n (%) | >.999 | ||

| <10 | 39 (50) | 176 (50) | |

| ≥10 | 39 (50) | 178 (50) | |

| ECOG at infusion n (%) | .899 | ||

| 0 | 47 (60) | 208 (59) | |

| ≥1 | 31 (40) | 146 (41) | |

| Disease status, n (%) | .217 | ||

| Relapsed | 18 (23) | 108 (31) | |

| Refractory | 60 (77) | 246 (69) | |

| No. of previous lines, n (%) | .353 | ||

| 1-2 | 56 (72) | 232 (66) | |

| >2 | 22 (28) | 122 (34) | |

| No. of extranodal sites, n (%) | >.999 | ||

| 0-2 | 66 (85) | 299 (84) | |

| >2 | 9 (11) | 42 (12) | |

| Missing | 3 (4) | 13 (4) | |

| Previous ASCT, n (%) | .332 | ||

| Yes | 18 (23) | 102 (29) | |

| No | 60 (77) | 252 (71) | |

| ORR to bridge, n (%) | .502 | ||

| No response | 49 (63) | 172 (49) | |

| Response | 25 (32) | 107 (30) | |

| Missing | 4 (5) | 75 (21) | |

| Bulky disease, n (%) | .063 | ||

| Yes | 33 (42) | 110 (31) | |

| No | 45 (58) | 244 (69) | |

| CAR T-cell therapy product, n (%) | >.999 | ||

| Axi-cel | 38 (49) | 172 (49) | |

| Tisa-cel | 40 (51) | 182 (51) | |

| Vein-to-vein time, median (range), mo | 1.6 (1.3-2.3) | 1.6 (1.4-2.3) | .639 |

| Time from diagnosis to infusion, median (range), mo | 12.7 (9.5-22.5) | 17.7 (11.2-43.3) | .002 |

| CAR-HEMATOTOX score, n (%) | .743 | ||

| Low (0-1) | 29 (37) | 144 (41) | |

| High (≥2) | 19 (24) | 83 (23) | |

| Missing | 30 (39) | 127 (36) |

| Characteristics . | HGBL (N = 78) . | DLBCL (N = 354) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | .191 | ||

| Female | 33 (42) | 120 (34) | |

| Male | 45 (58) | 234 (66) | |

| Age, median (range), y | 63 (55.5-68.0) | 60 (52.0-67-0) | .025 |

| Histology, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| HGBL-DH | 50 (64) | ||

| HGBL-NOS | 23 (30) | ||

| DLBCL MYC/BCL6 | 5 (6) | ||

| De novo | 278 (79) | ||

| Indolent transformed | 76 (21) | ||

| IPI, n (%) | .004 | ||

| 0-2 | 31 (40) | 205 (58) | |

| >2 | 47 (60) | 149 (42) | |

| LDH at infusion, n (%) | .765 | ||

| Normal | 46 (59) | 203 (57) | |

| Increased | 18 (23) | 90 (26) | |

| Missing | 14 (18) | 61 (17) | |

| CRP at infusion, n (%) | >.999 | ||

| <10 | 39 (50) | 176 (50) | |

| ≥10 | 39 (50) | 178 (50) | |

| ECOG at infusion n (%) | .899 | ||

| 0 | 47 (60) | 208 (59) | |

| ≥1 | 31 (40) | 146 (41) | |

| Disease status, n (%) | .217 | ||

| Relapsed | 18 (23) | 108 (31) | |

| Refractory | 60 (77) | 246 (69) | |

| No. of previous lines, n (%) | .353 | ||

| 1-2 | 56 (72) | 232 (66) | |

| >2 | 22 (28) | 122 (34) | |

| No. of extranodal sites, n (%) | >.999 | ||

| 0-2 | 66 (85) | 299 (84) | |

| >2 | 9 (11) | 42 (12) | |

| Missing | 3 (4) | 13 (4) | |

| Previous ASCT, n (%) | .332 | ||

| Yes | 18 (23) | 102 (29) | |

| No | 60 (77) | 252 (71) | |

| ORR to bridge, n (%) | .502 | ||

| No response | 49 (63) | 172 (49) | |

| Response | 25 (32) | 107 (30) | |

| Missing | 4 (5) | 75 (21) | |

| Bulky disease, n (%) | .063 | ||

| Yes | 33 (42) | 110 (31) | |

| No | 45 (58) | 244 (69) | |

| CAR T-cell therapy product, n (%) | >.999 | ||

| Axi-cel | 38 (49) | 172 (49) | |

| Tisa-cel | 40 (51) | 182 (51) | |

| Vein-to-vein time, median (range), mo | 1.6 (1.3-2.3) | 1.6 (1.4-2.3) | .639 |

| Time from diagnosis to infusion, median (range), mo | 12.7 (9.5-22.5) | 17.7 (11.2-43.3) | .002 |

| CAR-HEMATOTOX score, n (%) | .743 | ||

| Low (0-1) | 29 (37) | 144 (41) | |

| High (≥2) | 19 (24) | 83 (23) | |

| Missing | 30 (39) | 127 (36) |

ASCT, autologous stem cell transplant; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Nine patients in the HGBL subgroup were transformed from previous follicular NHL.

Seventy-eight patients had a diagnosis of HGBL, and 354 of DLBCL. The HGBL group included 50 patients with HGBL-DH/TH (64%), 23 with HGBL-NOS (30%), and 5 with DLBCL with MYC/BCL6 rearrangements (6%), previously classified as double-hit. Nine HGBL cases (12%) were transformed from previous indolent NHL, primarily follicular lymphoma. Among patients with DLBCL, 278 out of 354 (79%) had a diagnosis of de novo DLBCL, and 76 out of 354 (21%) had transformed from indolent NHL.

The median age was 63 years (range, 55-68 years) and 60 years (range, 52-67 years) for HGBL and DLBCL, respectively. All the patients received either axi-cel (n = 210, 49%) or tisa-cel (n = 222, 51%).

Most of the patients received BT (n = 74 of 78 in the HGBL group, 95%, and 278 of 354 in the DLBCL group, 79%, P < .001; all details are reported in Table 2). The overall response rates (ORRs) were 34% and 38%, while the complete response (CR) rate was 16% and 14% in the HGBL and DLBCL groups, respectively (P value ORR, .468; P value CR rate, .630). Polatuzumab-based chemotherapy was used as a bridging strategy in 15 of 74 (20%) and 62 of 278 (22%) patients, and achieved an ORR/CR of 53%/27% and 53%/21% for HGBL and DLBCL, with no significant difference between the 2 subtypes.

BT in the 2 subtypes

| BT, n (%) . | HGBL (N = 78) . | DLBCL (N = 354) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 4 (5) | 75 (21) | <.001 |

| Yes | 74 (95) | 279 (79) | |

| BT therapies | |||

| Chemoimmunotherapy∗ | 34 (46) | 172 (62) | |

| Radiotherapy | 17 (23) | 52 (19) | |

| Chemotherapy + radiotherapy | 10 (14) | 18 (6) | |

| Others | 9 (12) | 22 (8) | |

| Missing | 4 (5) | 15 (5) | |

| Antibody drug conjugate | |||

| Polatuzumab-based (included in chemoimmunotherapy) | 15 (20) | 61 (22) |

| BT, n (%) . | HGBL (N = 78) . | DLBCL (N = 354) . | P value . |

|---|---|---|---|

| No | 4 (5) | 75 (21) | <.001 |

| Yes | 74 (95) | 279 (79) | |

| BT therapies | |||

| Chemoimmunotherapy∗ | 34 (46) | 172 (62) | |

| Radiotherapy | 17 (23) | 52 (19) | |

| Chemotherapy + radiotherapy | 10 (14) | 18 (6) | |

| Others | 9 (12) | 22 (8) | |

| Missing | 4 (5) | 15 (5) | |

| Antibody drug conjugate | |||

| Polatuzumab-based (included in chemoimmunotherapy) | 15 (20) | 61 (22) |

Boldface highlights the patients who had received bridging therapy.

Monotherapy (single chemotherapy drug) was used in 3 patients with HGBL and in 34 with DLBCL, respectively.

Before weighting, patients with DLBCL were younger, with a higher proportion of males (Table 3). In addition, among patients with DLBCL, we observed an inferior proportion affected by refractory disease and treated with BT. Of note, the proportion of patients presenting with bulky disease was higher in patients with a diagnosis of HGBL.

Unweighted and weighted patient characteristics are included in the propensity score estimation

| . | Before IPW . | After IPW . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGBL (n = 78) . | DLBCL (n = 354) . | SMD . | HGBL (n = 78) . | DLBCL (n = 77.8) . | SMD . | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 63 (55.5-68) | 60 (62-67) | 0.292 | 63 (55-68) | 63 (56-68) | 0.010 |

| Sex male, n (%) | 45 (57.7) | 234 (66.1) | 0.174 | 45 (57.7) | 44.8 (57.5) | 0.004 |

| CRP at infusion ≥10, n (%) | 39 (50) | 178 (50.3) | 0.006 | 39 (50) | 38.6 (49.6) | 0.008 |

| ECOG ≥1, n (%) | 31 (39.7) | 146 (41.2) | 0.031 | 31 (39.7) | 30.4 (39) | 0.014 |

| Disease status, refractory, n (%) | 60 (76.9) | 246 (69.5) | 0.168 | 60 (76.9) | 60.3 (77.5) | 0.014 |

| IPI >2, n (%) | 47 (60.3) | 149 (42.1) | 0.370 | 47 (60.3) | 47.1 (60.5) | 0.005 |

| No. of prior lines >2, n (%) | 22 (28.2) | 122 (34.5) | 0.135 | 22 (28.2) | 22.3 (28.6) | 0.009 |

| Previous ASCT, n (%) | 18 (23.1) | 102 (28.8) | 0.131 | 18 (23.1) | 17.5 (22.4) | 0.015 |

| Response to bridge, n (%) | 0.498 | 0.018 | ||||

| No bridge | 4 (5.1) | 75 (21.2) | 4 (5.1) | 4 (5.1) | ||

| No response | 49 (62.8) | 172 (48.6) | 49 (62.8) | 48.3 (62) | ||

| Response | 25 (32.1) | 107 (30.2) | 25 (32.1) | 25.6 (32.9) | ||

| Bulky disease, n (%) | 33 (42.3) | 110 (31.1) | 0.235 | 33 (42.3) | 31.9 (40.9) | 0.028 |

| CAR T-cell therapy product tisa-cel, n (%) | 40 (51.3) | 182 (51.4) | 0.003 | 40 (51.3) | 39.8 (51.1) | 0.004 |

| Time from leukapheresis to infusion, median (IQR), mo | 1.6 (1.29-2.26) | 1.61 (1.35-2.27) | 0.115 | 1.58 (1.28-2.26) | 1.61 (1.37-2.14) | 0.022 |

| . | Before IPW . | After IPW . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGBL (n = 78) . | DLBCL (n = 354) . | SMD . | HGBL (n = 78) . | DLBCL (n = 77.8) . | SMD . | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 63 (55.5-68) | 60 (62-67) | 0.292 | 63 (55-68) | 63 (56-68) | 0.010 |

| Sex male, n (%) | 45 (57.7) | 234 (66.1) | 0.174 | 45 (57.7) | 44.8 (57.5) | 0.004 |

| CRP at infusion ≥10, n (%) | 39 (50) | 178 (50.3) | 0.006 | 39 (50) | 38.6 (49.6) | 0.008 |

| ECOG ≥1, n (%) | 31 (39.7) | 146 (41.2) | 0.031 | 31 (39.7) | 30.4 (39) | 0.014 |

| Disease status, refractory, n (%) | 60 (76.9) | 246 (69.5) | 0.168 | 60 (76.9) | 60.3 (77.5) | 0.014 |

| IPI >2, n (%) | 47 (60.3) | 149 (42.1) | 0.370 | 47 (60.3) | 47.1 (60.5) | 0.005 |

| No. of prior lines >2, n (%) | 22 (28.2) | 122 (34.5) | 0.135 | 22 (28.2) | 22.3 (28.6) | 0.009 |

| Previous ASCT, n (%) | 18 (23.1) | 102 (28.8) | 0.131 | 18 (23.1) | 17.5 (22.4) | 0.015 |

| Response to bridge, n (%) | 0.498 | 0.018 | ||||

| No bridge | 4 (5.1) | 75 (21.2) | 4 (5.1) | 4 (5.1) | ||

| No response | 49 (62.8) | 172 (48.6) | 49 (62.8) | 48.3 (62) | ||

| Response | 25 (32.1) | 107 (30.2) | 25 (32.1) | 25.6 (32.9) | ||

| Bulky disease, n (%) | 33 (42.3) | 110 (31.1) | 0.235 | 33 (42.3) | 31.9 (40.9) | 0.028 |

| CAR T-cell therapy product tisa-cel, n (%) | 40 (51.3) | 182 (51.4) | 0.003 | 40 (51.3) | 39.8 (51.1) | 0.004 |

| Time from leukapheresis to infusion, median (IQR), mo | 1.6 (1.29-2.26) | 1.61 (1.35-2.27) | 0.115 | 1.58 (1.28-2.26) | 1.61 (1.37-2.14) | 0.022 |

IPW, inverse probability weighting; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Efficacy and outcomes

With a median follow-up of 17.66 months, the estimated 2-year PFS, DOR, and OS of the entire population were 33% (95% CI, 28-39), 44% (95% CI, 37-52), and 47% (95% CI, 41-53), respectively.

In patients with HGBL (median follow-up, 22.86 months; IQR, 9.14-24.84), the estimated 2-year PFS, DOR, and OS were 34% (95% CI, 24-48), 47% (95% CI, 33-67), and 37% (95% CI, 27-51), respectively.

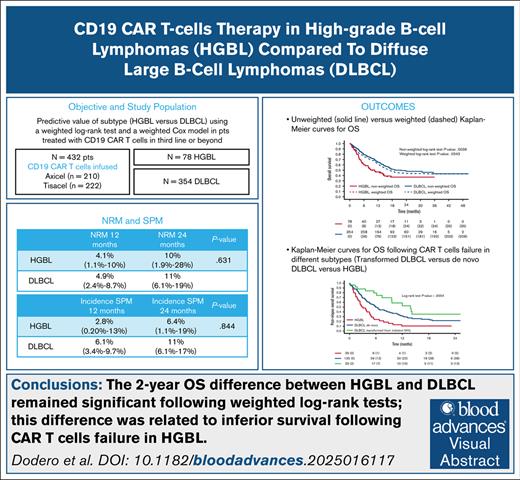

A univariable prognostic analysis for PFS and OS was conducted for HGBL (supplemental Table 1). There was no statistically significant difference in PFS and OS between patients with HGBL-DH/TH lymphomas and those with other histotypes (HGBL-NOS and Myc/bcl6; Figure 1). Achieving a CR before the infusion of CAR T-cell therapy was linked to a lower risk of progression, but did not affect OS (HR, 0.36, P = .026; HR, 0.45, P = .089). The tumor burden (bulky disease) before infusion was associated with a higher risk of failure and reduced OS (HR, 2.36, P = .004; HR, 3.17, P < .001). Patients with higher CAR-Hematotox levels had significantly poorer OS (15% vs 50%, P = .0096). The CAR T-cell therapy product (axi-cel or tisa-cel) did not influence PFS and OS (supplemental Table 1).

Survival outcomes in HGBL. Kaplan-Meier curves of OS (A) and PFS (B) for HGBL MYC/BCL2 vs other HGBL histotypes (HGBL-NOS and MYC/BCL6). P value for OS, .6993; P value for PFS, .6231.

Survival outcomes in HGBL. Kaplan-Meier curves of OS (A) and PFS (B) for HGBL MYC/BCL2 vs other HGBL histotypes (HGBL-NOS and MYC/BCL6). P value for OS, .6993; P value for PFS, .6231.

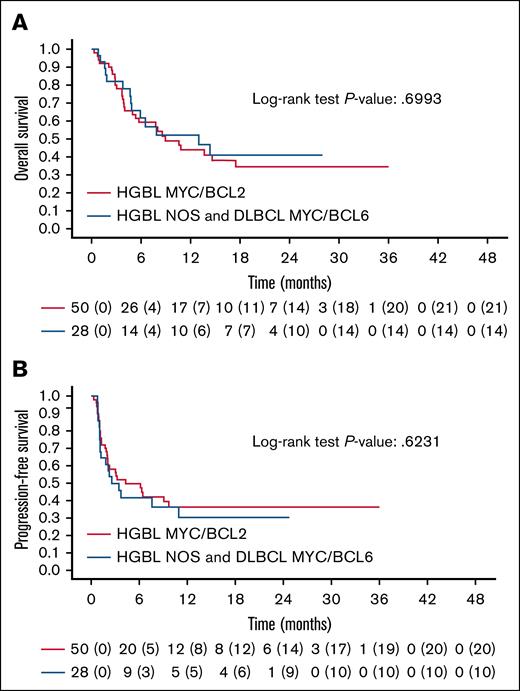

With a median follow-up of 18, 20 months (IQR, 11.58, 24.9), the estimated 2-year PFS, DOR, and OS in DLBCL were 33% (95% CI, 28-39), 43% (95% CI, 36-52), and 49% (95% CI, 42-55), respectively. Patients with transformed DLBCL (n = 76) had better outcomes than patients with de novo DLBCL (n = 278; 2-year PFS: 43% vs 30%, P = .0052; 2-year OS: 62% vs 45%, P = .0037; Figure 2). Achieving CR or CR/partial remission at infusion after bridging was linked to lower progression risk and better OS. Elevated CRP, lactate dehydrogenase, and bulky disease correlated with worse PFS and OS (supplemental Table 2). Tisa-cel increased failure risk (HR, 1.44, P = .008), but did not affect OS (supplemental Table 2).

Survival outcomes in DLBCL. Kaplan-Meier curves of OS (A) and PFS (B) of DLBCL transformed as compared to DLBCL de novo. P value for OS, .0037; P value for PFS, .0052.

Survival outcomes in DLBCL. Kaplan-Meier curves of OS (A) and PFS (B) of DLBCL transformed as compared to DLBCL de novo. P value for OS, .0037; P value for PFS, .0052.

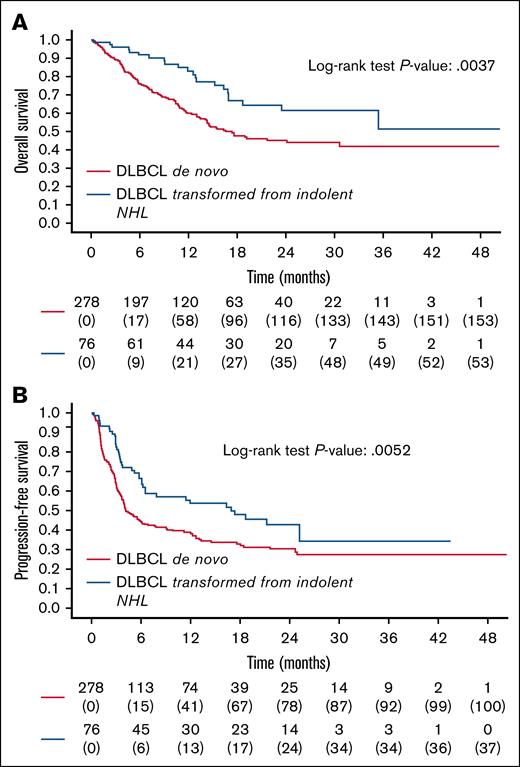

Univariable analysis showed significantly lower OS in patients with HGBL compared with patients with DLBCL, with a 2-year OS of 37% (95% CI, 27-55) vs 49% (95% CI, 42-55; log-rank P = .0036). PFS and DOR were not significantly different between the 2 subtypes, with 2-year PFS of 34% for HGBL (95% CI, 24-48) and 33% for DLBCL (95% CI, 28-39; log-rank P = .2772), and 2-year DOR of 47% for HGBL (95% CI, 33-67) and 43% for DLBCL (95% CI, 36-52; log-rank P = .7459).

Efficacy and outcomes after inverse probability weighting

A weighted comparison analysis was conducted to better discriminate the impact of the histological subtype on survival outcomes, postulating that the different biology would have led to different results. After the application, the patients with HGBL and DLBCL were balanced for several covariates, including age, sex, CRP, IPI, bulky disease, number of prior treatment lines, disease status (refractory vs relapsed), prior autologous stem cell transplant, response to BT, CAR T-cell therapy product, and vein-to-vein time. The weighted population included 155 patients divided equally between HGBL and DLBCL. There were no significant differences in terms of overall response rate (ORR) and CR rate at day +90 between HGBL and DLBCL (weighted logistic regression: odds ratio (OR) = 1.08, P = .811; OR = 1.18, P = .627). After weighting, a significant difference in 2-year OS (37% vs 44%, weighted log-rank P = .0343) but not in PFS (34% vs 31%, weighted log-rank P = .6127) or DOR (47% vs 44%, weighted log-rank P = .8252) was observed between HGBL and DLBCL (Tables 3 and 4; Figure 3).

Comparative analyses of HGBL vs DLBCL. Unweighted (solid line) vs weighted (dashed) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS (A), PFS (B), and DOR (C).

Comparative analyses of HGBL vs DLBCL. Unweighted (solid line) vs weighted (dashed) Kaplan-Meier curves for OS (A), PFS (B), and DOR (C).

Association of CAR T-cell therapy expansion with clinical response

Centrally performed in vivo expansion data covered 43 of 78 (55%) HGBL and 50 of 354 (14%) DLBCL cases. For HGBL, median CAR T-cell therapy levels at day 10 (C10), concentration of CAR T cells at the time of maximal expansion (Cmax), and magnitude of expansion up to 30 days calculated as the area under the curve (AUC0-30) were 21/μl, 53/μl, and 108/μl, with no significant differences between responders and nonresponders (supplemental Figure 1). For DLBCL, these were 30/μl, 61.5/μl, and 122.4/μl, respectively, with Cmax and AUC0-30, but not C10, differing significantly between responders and nonresponders (supplemental Figure 2; supplemental Table 3).

NRM and safety

NRM rates were superimposable for patients with HGBL and DLBCL, with 12-month and 24-month rates of 4.1% vs 4.9%, and 10% vs 11%, respectively (P = .631). Infections (including COVID infections) caused most deaths. No deaths were related to cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or immune effector cell–associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS). Deaths occurred in 12 patients who received axi-cel, and in 9 treated with tisa-cel.

Among patients with HGBL, 71 (91%) experienced CRS of any grade, including 10 (14%) with grade 3 to 4 CRS. Additionally, 25 (32%) developed ICANS of any grade, with 6 (24%) grades 3 to 4. Among DLBCL, 290 (82%) developed CRS of any grade, with 24 (8.4%) grades 3 to 4, and 66 (19%) developed ICANS of any grade, with 22 (33%) grades 3 to 4. Eleven patients with HGBL (14%) and 35 with DLBCL (8%) required intensive care unit admission.

In the univariable logistic model, the CRS and ICANS of any grade, but not the severity of presentation, were significantly inferior in DLBCL compared to HGBL (CRS, OR = 0.45; P = .037; ICANS, OR = 0.49, P = .012). However, the weighted logistic regression model did not show any difference between the 2 groups.

Treatment with tisa-cel was linked to a significantly lower incidence of any-grade CRS and ICANS (not severe) in HGBL and DLBCL (supplemental Tables 8-11). We identified 24 of 432 (5.6%) with SPM, which occurred at the median time of 10.3 months after CAR T-cell therapy infusion. Of these, 16 (66%) were classified as myeloid malignancies. Two patients died following a second malignancy. The cumulative incidence of SPM and second myeloid malignancies at 24 months was not significantly different between HGBL and DLBCL, with rates of 6.4% and 11% (P = .844), and 2.9% and 7.5% (P = .924), respectively.

Salvage therapy after CAR T-cell therapy failure

A total of 246 patients (57%) experienced disease progression following CAR T-cell therapy (n = 44 HGBL, n = 202 DLBCL) at a median time of 2.8 months (range, 0.36-25 months) after the infusion. Most relapses occurred within 6 months of the infusion, while only a minority (15.5% of HGBL and 17.9% of DLBCL) experienced progression beyond 6 months (median times to relapse for HGBL and DLBCL were 1.8 months [IQR, 1.1-3.1 months] and 2.8 months [IQR, 1.2-4.0 months], respectively).

The estimated 1-year OS for the cohort after CAR T-cell therapy failure was 21% (95% CI, 15-28), with a median OS of 5.7 months (range, 2.37-14 months). We performed a detailed analysis of patients with HGBL (n = 40) and those with DLBCL (n = 167) who relapsed or were refractory after CAR T-cell therapy. Due to incomplete data on disease characteristics at relapse, a subset of 39 patients was excluded from subsequent analyses (specifically, only 4 with HGBL and 35 with DLBCL). Patient characteristics in the 2 cohorts are summarized in supplemental Table 12. Of note, most of the patients with HGBL relapsed in the first 3 months after CAR T-cell therapy (n = 30/40, 75%), whereas a substantial proportion (n = 76/167, 46%) of patients with DLBCL relapsed beyond 3 months (P = .020). Among evaluable patients, 170 (82.1%) underwent salvage therapy after CAR T-cell therapy failure, whereas 37 (17.9%) received supportive care only. The proportion of patients not treated was 8 (20%) and 29 (17.4%) in HGBL and DLBCL, respectively.

Treatments for relapsed or refractory disease following CAR T-cell therapy are described in Table 5 and supplemental Figure 3. However, the rate of complete remission to any therapy after CAR T-cell therapy failure was significantly different between HGBL and DLBCL (16% vs 37%, respectively, P = .011). The use of bispecific antibodies was similar between HGBL (n = 15, 46.9%) and DLBCL (n = 62, 44.9%). The response rates to salvage bispecific antibodies were 3 of 11 CRs in HGBL (27%), and 14 of 40 CRs in DLBCL (35%). In addition, only 1 patient (3.1%) in the HGBL cohort underwent consolidation with allogeneic transplantation, compared with 24 (17.4%) in the DLBCL cohort.

PFS, OS, and DOR before and after propensity score IPW

| Survival . | Before IPW . | After IPW . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGBL (n = 78) . | DLBCL (n = 354) . | P value . | HGBL (n = 78) . | DLBCL (n = 77.8) . | P value . | |

| 2-year PFS, % (95% CI) | 34.2 (24.4-47.9) | 32.8 (27.5-39) | .2772 | 34.2 (22.7-45.7) | 31.6 (24.7-38.5) | .6127 |

| 2-year OS, % (95% CI) | 36.8 (26.5-51.2) | 48.5 (42.5-55.3) | .0036 | 36.8 (24.7-49) | 44.3 (36.4-52.2) | .0343 |

| 2-year DOR, % (95% CI) | 46.9 (32.9-66.8) | 43.3 (35.8-52.2) | .7459 | 46.9 (30.3-63.5) | 44.5 (34.3-54.8) | .8252 |

| Survival . | Before IPW . | After IPW . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HGBL (n = 78) . | DLBCL (n = 354) . | P value . | HGBL (n = 78) . | DLBCL (n = 77.8) . | P value . | |

| 2-year PFS, % (95% CI) | 34.2 (24.4-47.9) | 32.8 (27.5-39) | .2772 | 34.2 (22.7-45.7) | 31.6 (24.7-38.5) | .6127 |

| 2-year OS, % (95% CI) | 36.8 (26.5-51.2) | 48.5 (42.5-55.3) | .0036 | 36.8 (24.7-49) | 44.3 (36.4-52.2) | .0343 |

| 2-year DOR, % (95% CI) | 46.9 (32.9-66.8) | 43.3 (35.8-52.2) | .7459 | 46.9 (30.3-63.5) | 44.5 (34.3-54.8) | .8252 |

IPW, inverse probability weighting.

Salvage therapies following CAR T-cell therapy failure

| . | HGBL (N = 40)∗ . | DLBCL (N = 167)∗ . |

|---|---|---|

| No salvage treatment, n (%) | 8 | 29 |

| Salvage treatment, n (%) | 32 | 138 |

| First subsequent treatment after CAR T-cell therapy failure, n (%)† | ||

| Bispecific antibody | 11 (34.4) | 40 (29) |

| Anti-CD19 antibody-drug conjugate ± BTKi or lenalidomide | 0 (0) | 9 (6.5) |

| Polatuzumab-based regimens | 4 (12.5) | 25 (18.2) |

| RT | 0 (0) | 11 (7.9) |

| Chemo | 9 (28.1) | 26 (18.8) |

| Others (BTKi, IMiDs, CPI, anti-ROR1) | 8 (25) | 27 (19.6) |

| Bispecific antibody as first or subsequent salvage therapy after CAR T-cell therapy failure, n (%)† | 15 (46.9) | 62 (44.9) |

| No. of treatment lines after CAR T-cell therapy failure, n (%)† | ||

| 1 | 25 (78.1) | 79 (57.2) |

| >1 | 7 (21.9) | 59 (42.8) |

| AlloSCT after CAR T-cell therapy failure, n (%)† | 1 (3.1) | 24 (17.4) |

| . | HGBL (N = 40)∗ . | DLBCL (N = 167)∗ . |

|---|---|---|

| No salvage treatment, n (%) | 8 | 29 |

| Salvage treatment, n (%) | 32 | 138 |

| First subsequent treatment after CAR T-cell therapy failure, n (%)† | ||

| Bispecific antibody | 11 (34.4) | 40 (29) |

| Anti-CD19 antibody-drug conjugate ± BTKi or lenalidomide | 0 (0) | 9 (6.5) |

| Polatuzumab-based regimens | 4 (12.5) | 25 (18.2) |

| RT | 0 (0) | 11 (7.9) |

| Chemo | 9 (28.1) | 26 (18.8) |

| Others (BTKi, IMiDs, CPI, anti-ROR1) | 8 (25) | 27 (19.6) |

| Bispecific antibody as first or subsequent salvage therapy after CAR T-cell therapy failure, n (%)† | 15 (46.9) | 62 (44.9) |

| No. of treatment lines after CAR T-cell therapy failure, n (%)† | ||

| 1 | 25 (78.1) | 79 (57.2) |

| >1 | 7 (21.9) | 59 (42.8) |

| AlloSCT after CAR T-cell therapy failure, n (%)† | 1 (3.1) | 24 (17.4) |

AlloSCT, allogeneic stem cell transplantation; BTKi, Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor; chemo, chemotherapy; CPI, immune checkpoint inhibitors; IMiDs, immunomodulatory drugs; RT, radiotherapy.

Four patients with HGBL and 35 patients with DLBCL who relapsed following CAR T-cell therapy were excluded from the analysis due to incomplete data on disease characteristics at relapse, precluding their inclusion in multivariate models.

All values were calculated on the population of patients who received a treatment.

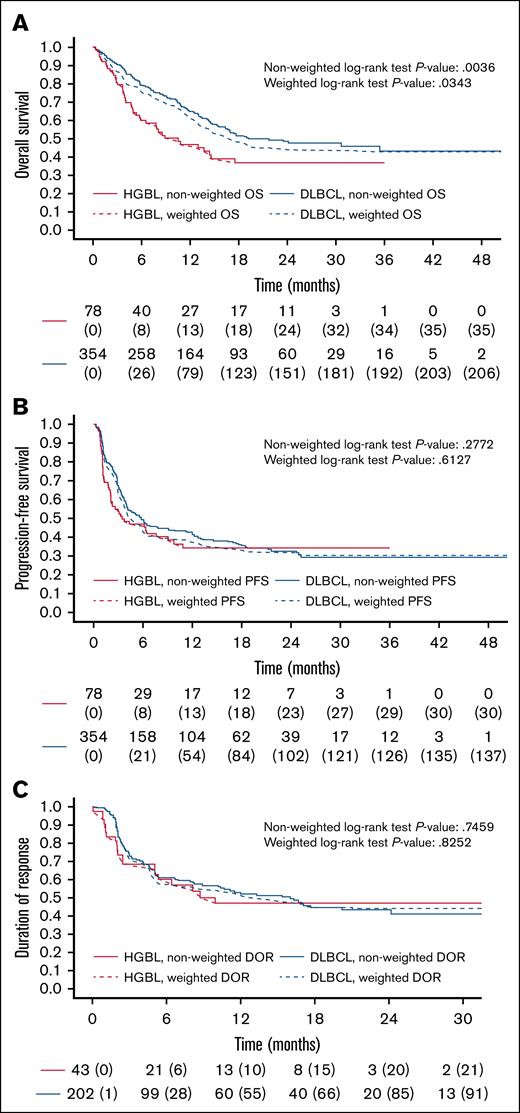

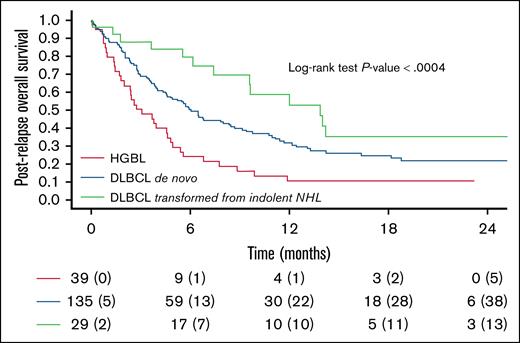

Patients treated with salvage therapy with bispecific antibodies experienced a significantly better outcome than those who received other treatments or no therapy (1-year postrelapse OS: 48% vs 25% vs 4%; P < .0001). Patients affected by transformed DLBCL showed a significantly superior 1-year postrelapse OS compared with those affected by de novo DLBCL and HGBL (1-year OS: 59% vs 32% vs 11%; P < .0004; Figure 4). In a multivariate model, treatment with bispecific antibodies, transformed DLBCL histology, and late relapse were all independently associated with improved prognosis (supplemental Table 13).

Kaplan-Meier curves for OS following CAR T-cell therapy failure in different subtypes (transformed DLBCL vs de novo DLBCL vs HGBL), P < .0004. For 4 of the evaluable patients, postrelapse OS could not be assessed as death occurred on the same day as disease progression.

Kaplan-Meier curves for OS following CAR T-cell therapy failure in different subtypes (transformed DLBCL vs de novo DLBCL vs HGBL), P < .0004. For 4 of the evaluable patients, postrelapse OS could not be assessed as death occurred on the same day as disease progression.

Discussion

CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy in the second and third lines has revolutionized the outcome of patients with relapsed/refractory LBCL. The efficacy of CAR T-cell therapy can differ among histological subtypes. However, pivotal and real-world studies have not fully explored this aspect.

In this study, the main objectives were to: (1) explore the efficacy and safety of CAR T-cell therapy in HGBL and DLBCL, with a particular focus on predictors of outcome; (2) analyze the predictive value of subtype (HGBL vs DLBCL) using a weighted log-rank test and weighted Cox model; and (3) evaluate the OS post–CAR T-cell therapy failure in the different subtypes.

To our knowledge, for the first time, we present a large group of patients affected by HGBL (n = 78). The estimated 2-year PFS, DOR, and OS rates for HGBL were 34% (95% CI, 24-48), 47% (95% CI, 33-67), and 37% (95% CI, 27-51), respectively. Additionally, we analyzed factors significantly influencing the outcome in HGBL, notably represented by bulky disease and response to BT (supplemental Table 1). Most patients with HGBL required BT (95%), but the overall response to BT was low (34%), with only 16% achieving CR. A higher CR rate was observed following polatuzumab-based regimens, which have previously been reported to enable CAR T-cell therapy in ∼70% of patients.12 Notably, attaining complete remission following BT was associated with an inferior risk of failure (PFS for CR: 55% vs 27%, P = .04), but did not influence OS. The study by Roddie et al13 confirmed a reduced risk of progression or death for those in clinical remission before CAR T-cell therapy infusion compared with nonresponders. Still, it included only a limited number of patients affected by HGBL.

Although the sample size was limited, we did not observe a significant difference in PFS, OS, and DOR between the HGBL-DH/TH and HGBL-NOS subtypes. This lack of significant differences may be related to the similarity in genomic characteristics between the 2 groups, as the double-hit signature was reported14 to be present in almost 54% of cases of HGBL-NOS.

Interestingly, none of expansion estimates (C10, Cmax, AUC0-30) correlated with tumor response, suggesting that other factors could be implicated in HGBL response. Furthermore, expansion should be assessed in a larger group of patients with HGBL to validate our findings.

After weighting, to account for the poor clinical prognostic characteristics of the HGBL cohort, we confirmed a significantly inferior OS in HGBL compared to DLBCL (2-year OS of 37% vs 44%, respectively). In contrast, no significant difference between the 2 subtypes was observed in PFS, DOR, or NRM.

So far, published data on CAR T-cell therapy in the third-line setting provided conflicting results in HGBL. In fact, in a real-world study conducted by Nastoupil et al,8 which exclusively used axi-cel as CAR T-cell therapy product, no significant difference in OS was found between patients affected by HGBL and those affected by DLBCL at a median follow-up of 12 months. Conversely, Shouval et al15 conducted a study involving 153 patients treated with several CAR T-cell therapy products: they reported that patients carrying rearrangement of MYC or DH/TH lymphomas had poorer OS than other lymphomas. Phina-Ziebin et al assessed patients with HGBL and DLBCL from the time of eligibility for CAR T-cell therapy.9 Dropout rates from eligibility to infusion were similar for HGBL and non-HGBL (18% vs 13%). However, OS was significantly lower for HGBL-DH/TH compared to non-HGBL from the eligibility date, but not from the infusion date, indicating that the survival difference disappeared among those who received infusion.

On the other hand, studies that utilized CAR T-cell therapy in the second line or even in the first line demonstrated that the early use of CAR T-cell therapy might help to overcome the biological aggressiveness of HGBL. In pivotal studies on the use of CAR T-cell therapy in the second line, a limited number of patients with HGBL were included, but an overall survival advantage was present in both patients with HGBL and DLBCL.16 Furthermore, the use of the CAR T-cell therapy in the first line, as reported by the Zuma-12 trial, was associated with a high ORR and PFS of 74% at 12 months in patients with a positive interim positron emission tomography and/or a diagnosis of DH/TH or DLBCL with high-intermediate or high-risk IPI scores.17 In our study, we showed transformed DLBCL had better outcomes than de novo DLBCL in PFS and OS (2-year PFS: 43% vs 30%, P = .0052; 2-year OS: 62% vs 45%, P = .0037). This was mainly reported by Nydegger et al,18 analyzing 36 patients (half de novo, half transformed) mostly treated with tisa-cel.

In agreement with Jain et al,19 our study showed an increase in cumulative NRM over time, increasing from 4.1% and 4.9% at 12 months to 10% and 11% at 24 months in HGBL and DLBCL, respectively, without any significant difference between the 2 histotypes. The leading cause of death was infection. Our findings are also similar to those described by Cordas dos Santos et al,20 who found a 1-year NRM of 6.1% in all aggressive lymphomas, with 50% of deaths attributed to infections. Recently, Ghilardi et al reported an incidence of second malignancies of 3.6% following commercial CD19 and B-cell maturation antigen-directed CAR T-cell therapy products, with age >65 years at the time of CAR T-cell therapy infusion as the only predisposing factor.21 We had previously described an incidence of SPM of 4.3% in the CART SIE observational study with a median follow-up of 12 months.22 Here, we reported an incidence of 5.6% with a median follow-up of 2 years. Despite differences in prior treatments between HGBL and DLBCL, no significant variations were observed in the cumulative incidence of SPM and myeloid malignancies in the 2 subtypes (SPM 6.4% vs 11% and myeloid malignancies 2.9% vs 7.9%, for HGBL vs DLBCL, respectively).

Various studies have reported unfavorable outcomes for patients who progress or relapse after CAR T-cell therapy, which occurs in nearly 60% of cases. Available data suggest that the worst outcomes are experienced by patients with early progression, particularly those progressing within 2 months of CAR T-cell therapy infusion, and by those not receiving salvage treatment.23-27 Tomas et al25 analyzed the outcomes of 182 patients with LBCL progressing after CD19-directed CAR T-cell therapy, including 20 patients with DH/TH. Of these, 135 (74%) received salvage therapy, achieving an ORR of 39%. The most common salvage regimens included polatuzumab-based therapies, lenalidomide-based regimens, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and BTK inhibitors. One-year OS following CAR T-cell therapy failure ranged from 25% for patients treated with chemotherapy to 69% for those treated with lenalidomide. Factors significantly associated with poor survival after CAR T-cell therapy failure included bulky disease, CAR T-cell therapy refractoriness, age, and elevated lactate dehydrogenase level at progression.

Iacoboni et al27 reported data from 387 patients with LBCL in whom CAR T-cell therapy failed, including 56 patients with HGBL. Sixty-one percent of the cohort received salvage treatment. The 12-month postrelapse OS for the entire population was 31%, with only 9% for nontreated patients and 44% for those receiving salvage therapy. The most effective salvage treatments included polatuzumab-based regimens and bispecific antibodies, achieving 38% and 36% CR rates, respectively. Patients with HGBL had significantly shorter PFS with the first subsequent treatment after CAR T-cell therapy failure than others.

In our study, 207 of 246 (84%) patients who relapsed were evaluable for all prognostic factors at the time of CAR T-cell therapy failure. Of note, most of the patients with HGBL relapsed within 3 months after infusion (30/40, 75%), whereas a substantial proportion (76/167, 46%) of the patients with DLBCL relapsed beyond 3 months (P = .020). This likely had a significant impact on the inferior OS group described in HGBL. Furthermore, the number of patients treated after CAR T-cell therapy failure and the use of bispecific antibodies was comparable between HGBL and DLBCL (salvage therapy, 80% vs 83%; use of bispecific antibodies, 46.9% vs 44.9%). A key finding is that the response to salvage in terms of CR was significantly inferior in HGBL compared to DLBCL (16% vs 37%). All these factors account for the poor outcome of patients affected by HGBL following CAR T-cell therapy failure (1-year postrelapse OS, 11%).

We acknowledge the limitations of our study, which include the absence of a central histological review of all diagnoses. Additionally, our study evaluated only patients who received infusion, so we have no data on dropout rates before infusion or OS from eligibility for CAR T-cell therapy in HGBL compared to DLBCL.

By employing inverse probability weighting, we were able to compare the outcomes of patients with HGBL and DLBCL while minimizing confounding factors, thereby ensuring a robust and balanced comparison between the 2 groups. Furthermore, trials investigating CAR T-cell therapy in second-line and first-line settings suggest that earlier use of this treatment may result in better outcomes. Patients with HGBL who experience progression after CAR T-cell therapy have a poor prognosis and require prompt salvage therapy with novel immunotherapies such as bispecific antibodies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, their families, and nurses. The authors also thank Sonia Perticone and the trial office of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi for managing the study, and Anna Fedina for exporting data.

This study is sponsored by Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Milan, Italy, “Associazione Italiana contro le Leucemie-linfomi e mieloma” Milano; “Società Italiana di Ematologia”; Italian Ministry of Health #PNC-E3-2022-23683269-PNC-HLS-TA. The research leading to these results received funding from Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro under IG 2024, ID.31005 project, principal investigator Corradini Paolo. This research project has received funding from Gilead (H24005).

Authorship

Contribution: A.D., G.C., A.C., and P. Corradini were responsible for conception and design of the study; S.L., A.D., G.C., A.C., and P. Corradini were responsible for the collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation; P.C. supervised the study; and all authors were responsible for provision of study materials or patients, writing and final approval of the manuscript, and were accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: A.D. participated in advisory boards for Takeda and AbbVie. B.C. participated in advisory boards for and received honoraria for lectures/educational events from Kite, Gilead, and Novartis. S.B. participated in speakers bureaus for Bristol Myers Squibb (BMS), Gilead, and Novartis; participated on an advisory board for Novartis; and reports travel accommodation expenses from Roche. A.C. participated in advisory boards for Gilead Sciences, Ideogen, Roche, Secura Bio, and Takeda; and reports honoraria for lectures/educational events from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, Incyte, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, and Takeda. A.D.R. reports consulting fees from Roche, Takeda, Incyte, Kite-Gilead, Novartis, and AbbVie; participated in speakers bureaus for Roche, Kite-Gilead, Janssen, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Sobi, Incyte, and Recordati Rare Disease; and participated in advisory boards for Takeda, Kite-Gilead, Roche, AbbVie, and Novartis. P.Z. acted as a consultant for Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Eusapharma, and Novartis; participated on advisory boards for ADC Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Celltrion, Eusapharma, Gilead, Incyte, Janssen-Cilag, Kyowa Kirin, MSD, Novartis, Roche, Sandoz, Secura Bio, Servier, and Takeda; and participated in speakers bureaus for AstraZeneca, BeiGene, BMS, Celltrion, Eusapharma, Gilead, Incyte, Janssen-Cilag, Kyowa Kirin, MSD, Novartis, Roche, Servier, and Takeda. P. Corradini participated on advisory boards for AbbVie, ADC Therapeutics, Amgen, BeiGene, Celgene, Daiichi Sankyo, Gilead/Kite, GlaxoSmithKline, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Nerviano Medical Science, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, and Takeda; and reports honoraria for lectures from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Gilead/Kite, Janssen, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, and Takeda. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Anna Dodero, Division of Hematology and Stem Cell transplantation, Fondazione Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, Via Venezian 1, 20133 Milan, Italy; email: anna.dodero@istitutotumori.mi.it.

References

Author notes

A.D. and G.C. contributed equally to this study.

Deidentified individual data are available on request from the corresponding author, Anna Dodero (anna.dodero@istitutotumori.mi.it), in accordance with institutional privacy policies.

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.