Key Points

Leukemias resist therapy via genetic, for example, TP53 mutation, and adaptive means, for example, reactive pyrimidine metabolism rewiring.

Both resistance modes can be parried by rational drug, dose, and schedule selection for noncytotoxic DNMT1 and DHODH targeting.

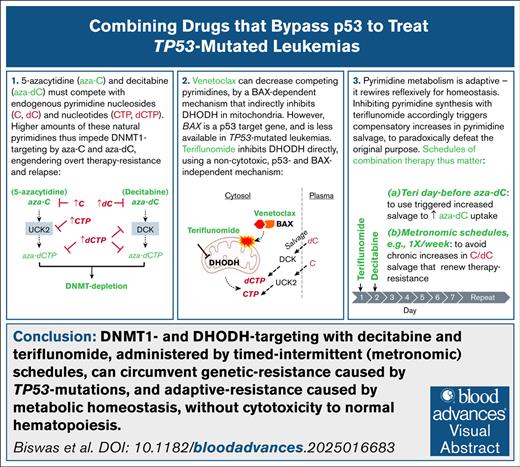

Visual Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemias (AML) containing TP53 (p53) mutations are routinely treated with decitabine or 5-azacytidine, which deplete DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1; ie, hypomethylating agents [HMA]). Unfortunately, resistance/relapse, characterized by preserved DNMT1, is rapid. HMA are pyrimidine analogs, and to deplete DNMT1, must compete with endogenous pyrimidines. These were substantially increased in HMA-resistant vs parental AML cells, together with upregulation of CAD (carbamoyl-phosphate-synthetase-2/aspartate transcarbamylase/dihydroorotase) that rate limits de novo pyrimidine synthesis. Moreover, TP53-mutated AML appeared primed for such resistance, with higher baseline CAD. Pyrimidine synthesis can be depowered with the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2) inhibitor venetoclax to release BCL-2–associated X protein (BAX) to depolarize mitochondrial membranes. However, BAX, a p53 target gene, was substantially less expressed in TP53-mutated vs wild-type TP53 cells, and venetoclax impacts were correspondingly limited. Alternatively, pyrimidine synthesis can be inhibited directly at dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) using the clinical drug teriflunomide. Contrasting with venetoclax, teriflunomide decreased pyrimidine levels several-fold, restored DNMT1 depletion, and cytoreduced HMA-resistant TP53-mutated AML cells via p53/apoptosis-independent terminal-differentiation. This noncytotoxic pathway preserved viability and proliferation of normal hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (NHSPCs). Inhibiting pyrimidine synthesis triggered compensatory pyrimidine salvage, such that schedules for teriflunomide combination with HMA, which are taken up by salvage, mattered. In mice with TP53-mutated AML, teriflunomide scheduled the day before HMA was more efficacious than same-day or day-after schedules. Chronic teriflunomide exposure paradoxically increased pyrimidines via sustained compensatory salvage, conferring resistance rather than sensitivity to HMA. In sum, DNMT1 and DHODH targeting, administered by timed, intermittent (metronomic) schedules, can circumvent genetic resistance caused by TP53 mutations and adaptive resistance caused by metabolic homeostasis, without cytotoxicity to HSPCs.

Introduction

Standard first-line treatment for TP53-mutated acute myeloid leukemias (AML) is with the DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1)–depleting pyrimidine analogs decitabine or 5-azacytidine (hypomethylating agents [HMA]).1,2 The TP53 product, p53, is the master transcription factor regulator of apoptosis, a program that senses stress; arrests cell cycle to allow for repair; and, if the stress persists, compels orderly cell suicide (cytotoxicity). Conventional antimetabolite chemotherapies, by inflicting cell stress/damage, aim to upregulate p53 and activate apoptosis as the pathway to terminate malignant replications. Loss-of-function genetic alterations in this pathway, for example, TP53 mutations/deletions, accordingly contribute to resistance/refractoriness to standard cytotoxic treatments.3,4 These treatments do, however, activate apoptosis in normal dividing cells, causing major short- and long-term clinical toxicities.3,4 DNMT1 targeting is an alternative treatment mode that can terminate malignant replications even when p53 is lost.5-8 A reason for this is that, in addition to its function as the maintenance methyltransferase, DNMT1 is a corepressor recruited into lineage master transcription factor hubs, and mediates aberrant epigenetic repression of lineage-maturation programs in transformed myeloid precursors.6,8-11 Depleting DNMT1 therefore releases cell cycling exits via lineage maturations, cell cycling exits that do not require p53 or the apoptosis program it regulates (reviewed in Velcheti et al12 and Zavras et al13). In keeping with these pathway observations, HMA have produced similar upfront clinical response rates of ∼50% in both TP53-mutated and wild-type TP53 myeloid neoplasms.2,7,14-17 Unfortunately, TP53-mutated cases relapse early, such that median overall survivals are very poor at ∼5 months2,7,14-17 (reviewed in Daver et al1). These poor survival rates have persisted despite routine addition of the B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL2)–inhibitor venetoclax to HMA. HMA/venetoclax has significantly augmented breadth and duration of response vs HMA alone in wild-type TP53 but not TP53-mutated AML.1,14,15 Investigation of resistance mechanisms to HMA and HMA/venetoclax in ways that point to practical solutions for early relapse, is thus a consensus priority.2,18-21

HMA are analogs of pyrimidines cytidine (5-azacytidine) and deoxycytidine (decitabine). Both 5-azacytidine and decitabine are processed by pyrimidine metabolism into a deoxycytidine triphosphate (dCTP) nucleotide analog, aza-dCTP, that effects DNMT1 depletion (reviewed in Zavras et al13). As per other metabolic networks, pyrimidine metabolism is adaptive, it senses and reconfigures as needed for cellular homeostasis. HMA interactions with this network trigger automatic adaptive responses that have been shown to dampen HMA processing into aza-dCTP, thus preventing DNMT1 depletion in target cells.8,22,23 One element in this adaptive resistance is upregulation of key de novo pyrimidine synthesis enzymes within the cells, for example, CAD (carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase 2/aspartate transcarbamylase/dihydroorotase), that rate limits synthesis of endogenous dCTP that competes with aza-dCTP.8,22,24 Moreover, we found here that CAD upregulation is a baseline feature of TP53-mutated AML cells, likely as a compensatory response to decreased amounts of ribonucleotide reductase p53-inducible subunit M2B (RRM2B), that produces deoxynucleotides and is a p53 target gene.25-27 Venetoclax, by inhibiting BCL2, can potentially counter upregulated de novo pyrimidine synthesis; BCL2-inhibition releases BCL-2–associated X protein (BAX) to depolarize mitochondrial membranes, depowering the mitochondrial step of de novo pyrimidine synthesis executed by dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH). However, as mentioned earlier, in patients with TP53-mutated AML, venetoclax added to HMA has not increased overall survivals vs HMA alone, for unclear reasons.1,14,15 We therefore further characterized HMA and HMA/venetoclax treatment resistance, and based on these results, evaluated clinically viable countermeasures in vitro and in vivo, with an overall goal of advancing mechanism-based solutions, able to treat even TP53-mutated disease.

Methods

Sources of cell lines and animals

AML cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Virginia) and reauthenticated after selection for resistance (Genetica DNA Laboratories, Burlington, NC; or Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primary AML cells for inoculation into mice were purchased from the Public Repository of Xenografts (proxe.org; Boston, MA). NSG mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Umbilical cord blood was purchased from Cleveland Cord Blood (Cleveland, OH).

DNMT1 immunodetection and quantitation

Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and high-resolution LC-MS

Treatment of a patient-derived xenotransplant (PDX) model of treatment-resistant AML

Primary AML cells from a patient with disease relapsed/refractory to standard chemotherapy, then salvaged with decitabine, and from a patient with chemotherapy-refractory TP53-mutated, complex cytogenetics AML, were transplanted by tail-vein injection (1.0 × 106 per mouse) into nonirradiated 6- to 8-week-old NSG mice anesthetized with isoflurane. Mice were randomized to different treatments, as indicated in each figure, on days 9 to 35 after inoculation. Tail-vein blood samples for blood count measurement by HemaVet were obtained before leukemia inoculation, and at intervals thereafter. Mice were observed daily for signs of pain or distress and were euthanized by an institutional animal care and use committee–approved protocol for such signs (details in the supplemental Methods).

Bioinformatic and statistical analysis

Mann-Whitney U and t tests were 2-sided, unless otherwise indicated. Standard deviations and interquartile ranges were calculated and represented as y-axis error bars on each graph. Curated public gene expression data were processed and analyzed as previously described10 and detailed in the figure legends. Graph Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, CA) or SAS statistical software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) was used to perform statistical analysis.

Results

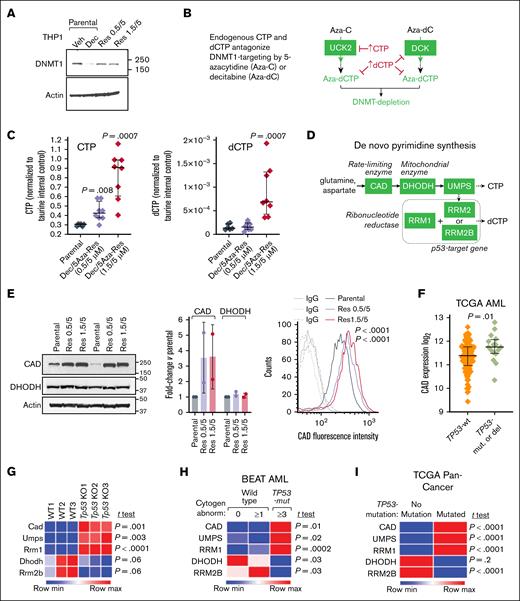

CTP and dCTP nucleotide levels are elevated in HMA-resistant AML cells

HMA-resistant TP53-mutated AML cells (THP1, p53/p16-null, chemotherapy-resistant5,6,30,31) emerged after ∼40 days of continuous culture in clinically relevant concentrations of decitabine and 5-azacytidine, 0.5/5μM or 1.5/5μM, added during media replacement every 3 days, as previously described.22 Treating parental (HMA-naïve) THP1 cells with 0.5μM decitabine depleted DNMT1 as expected (Figure 1A). However, DNMT1 protein was preserved in the HMA-resistant THP1 despite their continuous exposures to HMA (Figure 1A). We then investigated reasons for this failure to deplete DNMT1. aza-dCTP, the DNMT1-depleting deoxynucleotide metabolite of 5-azacytidine and decitabine, must compete with natural dCTP to deplete DNMT1 (Figure 1B). Therefore, we measured endogenous dCTP and also cytidine triphosphate (CTP) in HMA-resistant vs parental THP1 cells using high-resolution LC-MS. CTP was increased several-fold in both HMA-resistant lines vs parental cells (Figure 1C). dCTP was increased several-fold in the 1.5/5μM decitabine/5-azacytidine treatment, but not 0.5/5μM decitabine/5-azacytidine, HMA-resistant THP1 cells (Figure 1C; we have previously observed that higher decitabine concentrations cause off-target depletion of thymidylate synthase that decreases deoxythymidine triphosphate, hence disinhibiting ribonucleotide reductase to increase dCTP22).

CTP and dCTP are elevated, and DNMT1 protein is preserved in HMA-resistant AML cells. (A) DNMT1 depletion observed in parental AML cells treated with HMA was abrogated in HMA-resistant cells. HMA-resistant p53-null AML cells (THP1) emerged from continuous culture in decitabine/5-azacytidine 0.5/5μM and 1.5/5μM. Western blot using 50 μg total protein from each sample. (B) 5-Azacytidine and decitabine, analogs of cytidine and deoxycytidine, respectively, must compete with their endogenous pyrimidine nucleotide counterparts (CTP, dCTP) in order to deplete DNMT1. UCK2 and DCK are the pyrimidine metabolism enzymes that rate control conversion of 5-azacytidine and decitabine into DNMT1-depleting nucleotides. (C) CTP and dCTP were elevated in HMA-resistant AML cells. High-resolution LC-MS (HR-LCMS) analyses of extracts obtained from equal numbers of cells, harvested independently in octuplicate. Values are normalized to taurine levels in the same cells (taurine internal control). Data represent as means ± standard deviation (SD); P values are from unpaired, 2-sided t tests. (D) Key de novo pyrimidine synthesis enzymes. (E) The initial and rate-limiting enzyme in this pathway, CAD, was upregulated in HMA-resistant vs parental AML cells. Western blot (left). Replicates from independent cell harvests. Graph shows CAD intensity normalized to actin in the same sample using ImageJ software, fold change HMA-resistant vs parental THP1. CAD fluorescence intensity measured by flow cytometry in fixed/permeabilized cells and HMA-resistant vs parental cells (∼8900 cells each) (right). P values for mean fluorescence intensity between HMA-resistant vs parental cells were calculated using an unpaired 2-sided t test. (F) CAD expression in TP53-mutated vs wild-type (WT) TP53 AML cells. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) RNA-sequencing gene-level log2(x+1) transformed RNA-Seq by expectation-maximization (RSEM) normalized counts, primary AML cells containing WT TP53 (no TP53 mutations or deletions by genomic identification of significant targets in cancer (GISTIC) threshold analyses of copy number; n = 129) or containing mutated-TP53 and complex (≥3) cytogenetic abnormalities (n = 16). P values from unpaired 2-sided t test. (G) Tp53 knockout from GMP (lin–cKit+Sca–1–CD16/32+CD34+) decreases Rrm2b and activates other de novo pyrimidine synthesis enzymes, including Cad, Umps, and Rrm1. GSE285355,32 gene expression counts normalized via log transformation and size-factor adjustment.32 GMP isolated from Vav-cre Tp53fl/fl mice and age-matched WT mice.32P values, unpaired 2-sided t test. (H) TP53-mutated AML cells display a similar pyrimidine metabolism gene expression pattern. BEAT AML RNA-sequencing, gene-level counts processed by conditional quantile normalization,33 primary AML cells containing WT TP53 are subcategorized into cases with normal cytogenetics (n = 258) or ≥1 cytogenetic abnormality (n = 270), compared with primary AML cells containing mutated-TP53 and ≥3 cytogenetic abnormalities (n = 56); P values from unpaired 2-sided t test. (I) TP53-mutated pan-cancer cells display a similar pyrimidine metabolism gene expression pattern. TCGA Pan-Cancer, TP53-mutated (n = 3320) vs no TP53 mutations (n = 5760). RNA-sequencing and analyses as per panel F. Aza-C, 5-azacytidine; Aza-dC, decitabine; DEC, decitabine; IgG, immunoglobulin G; max, maximum; min, minimum; mut, mutated; Res, resistant; Veh, vehicle.

CTP and dCTP are elevated, and DNMT1 protein is preserved in HMA-resistant AML cells. (A) DNMT1 depletion observed in parental AML cells treated with HMA was abrogated in HMA-resistant cells. HMA-resistant p53-null AML cells (THP1) emerged from continuous culture in decitabine/5-azacytidine 0.5/5μM and 1.5/5μM. Western blot using 50 μg total protein from each sample. (B) 5-Azacytidine and decitabine, analogs of cytidine and deoxycytidine, respectively, must compete with their endogenous pyrimidine nucleotide counterparts (CTP, dCTP) in order to deplete DNMT1. UCK2 and DCK are the pyrimidine metabolism enzymes that rate control conversion of 5-azacytidine and decitabine into DNMT1-depleting nucleotides. (C) CTP and dCTP were elevated in HMA-resistant AML cells. High-resolution LC-MS (HR-LCMS) analyses of extracts obtained from equal numbers of cells, harvested independently in octuplicate. Values are normalized to taurine levels in the same cells (taurine internal control). Data represent as means ± standard deviation (SD); P values are from unpaired, 2-sided t tests. (D) Key de novo pyrimidine synthesis enzymes. (E) The initial and rate-limiting enzyme in this pathway, CAD, was upregulated in HMA-resistant vs parental AML cells. Western blot (left). Replicates from independent cell harvests. Graph shows CAD intensity normalized to actin in the same sample using ImageJ software, fold change HMA-resistant vs parental THP1. CAD fluorescence intensity measured by flow cytometry in fixed/permeabilized cells and HMA-resistant vs parental cells (∼8900 cells each) (right). P values for mean fluorescence intensity between HMA-resistant vs parental cells were calculated using an unpaired 2-sided t test. (F) CAD expression in TP53-mutated vs wild-type (WT) TP53 AML cells. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) RNA-sequencing gene-level log2(x+1) transformed RNA-Seq by expectation-maximization (RSEM) normalized counts, primary AML cells containing WT TP53 (no TP53 mutations or deletions by genomic identification of significant targets in cancer (GISTIC) threshold analyses of copy number; n = 129) or containing mutated-TP53 and complex (≥3) cytogenetic abnormalities (n = 16). P values from unpaired 2-sided t test. (G) Tp53 knockout from GMP (lin–cKit+Sca–1–CD16/32+CD34+) decreases Rrm2b and activates other de novo pyrimidine synthesis enzymes, including Cad, Umps, and Rrm1. GSE285355,32 gene expression counts normalized via log transformation and size-factor adjustment.32 GMP isolated from Vav-cre Tp53fl/fl mice and age-matched WT mice.32P values, unpaired 2-sided t test. (H) TP53-mutated AML cells display a similar pyrimidine metabolism gene expression pattern. BEAT AML RNA-sequencing, gene-level counts processed by conditional quantile normalization,33 primary AML cells containing WT TP53 are subcategorized into cases with normal cytogenetics (n = 258) or ≥1 cytogenetic abnormality (n = 270), compared with primary AML cells containing mutated-TP53 and ≥3 cytogenetic abnormalities (n = 56); P values from unpaired 2-sided t test. (I) TP53-mutated pan-cancer cells display a similar pyrimidine metabolism gene expression pattern. TCGA Pan-Cancer, TP53-mutated (n = 3320) vs no TP53 mutations (n = 5760). RNA-sequencing and analyses as per panel F. Aza-C, 5-azacytidine; Aza-dC, decitabine; DEC, decitabine; IgG, immunoglobulin G; max, maximum; min, minimum; mut, mutated; Res, resistant; Veh, vehicle.

Previously, we have observed upregulation of CAD, the initial and rate-limiting enzyme in the de novo pyrimidine synthesis pathway, in patient bone marrows at time of relapse on HMA therapy.22 Consistent with a contribution of de novo pyrimidine synthesis to elevated CTP in the HMA-resistant THP1, CAD protein was increased vs parental THP1, quantified by western blot and by flow cytometry (Figure 1D-E). DHODH, the enzyme downstream from CAD, was not markedly increased (Figure 1D-E).

Moreover, CAD was increased at baseline in TP53-mutated vs wild-type TP53 primary AML cells (Figure 1F), and in Tp53-knockout murine granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMP; Figure 1G). We also examined another de novo pyrimidine synthesis enzyme, RRM2B, because it (1) is a p53 target gene, (2) produces deoxynucleotides needed for repair and mitochondrial DNA, and (3) may therefore trigger compensatory increases in other de novo synthesis enzymes if suppressed.25-27RRM2B was suppressed in Tp53-knockout vs wild-type GMP (Figure 1G) and in TP53-mutated vs wild-type TP53 primary AML cells (Figure 1H), accompanied by increased de novo synthesis enzymes CAD, uridine monophosphate synthetase (UMPS), and ribonucleotide reductase catalytic subunit M1, but not DHODH (Figure 1G-H). In keeping with fundamental roles for p53, pyrimidine metabolism and the connection between the 2, this pattern was observed in primary cancer cells across the histological and genetic spectrum (pan-cancer; Figure 1I).

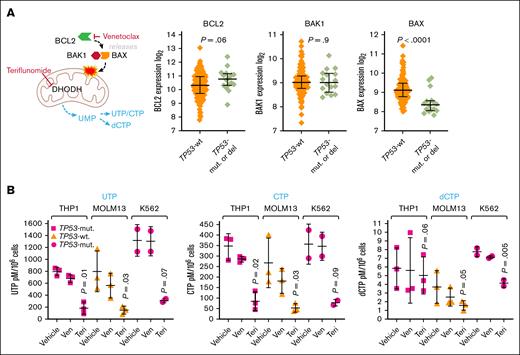

Teriflunomide had specific and larger impacts on CTP and dCTP levels than venetoclax

These results suggested that inhibiting de novo pyrimidine synthesis might counter HMA resistance, with a potential pathway bottleneck at DHODH. Venetoclax, by inhibiting BCL2, releases an effector protein, BAX, that in partnership with BCL2 antagonist/killer 1 (BAK1), depolarizes mitochondrial membranes, depowering pyrimidine synthesis at the mitochondrial step executed by DHODH.34 BAX, a p53 target gene,35,36 was approximately twofold less expressed in TP53-mutated vs wild-type TP53 AML cells, whereas BCL2 and BAK1 expression was similar (Figure 2A). To bypass BAX, an alternative is to inhibit pyrimidine synthesis at DHODH directly using the clinical drug teriflunomide. We therefore compared venetoclax vs teriflunomide effects on nucleotide levels. Venetoclax 2μM (20nM for MOLM13) or teriflunomide 20μM were added once to TP53-mutated THP1 and K562, and wild-type TP53 MOLM13 AML cells, and nucleotide levels were measured by LC-MS/MS 24 hours later (standard clinical doses of venetoclax and teriflunomide produce peak plasma concentrations of up to 2μM and 100μM, respectively). Teriflunomide reduced CTP and dCTP levels by several-fold more than venetoclax (Figure 2B; supplemental Figure 1). Teriflunomide did not significantly decrease levels of the purine ribonucleotides adenine triphosphate and guanine triphosphate, whereas venetoclax did (supplemental Figure 1).

Venetoclax and teriflunomide effects on CTP and dCTP levels. (A) BAX is a p53 target gene that is approximately twofold less expressed in TP53-mutated vs WT TP53 AML cells, whereas BCL2 and BAK1 are similarly expressed. TCGA RNA-sequencing gene-level log2(x+1) transformed RSEM normalized counts, primary AML cells containing WT TP53 (no TP53 mutations or deletions by GISTIC threshold analyses of copy number; n = 129) or containing mutated TP53 and complex (≥3) cytogenetic abnormalities (n = 16). P value from unpaired 2-sided t test. (B) Teriflunomide produced larger decreases in CTP and dCTP in TP53-mutated and WT-TP53 AML cells than venetoclax. Venetoclax 2μM (20nM for MOLM13) or teriflunomide 20μM were added once to THP1, K562, and MOLM13 AML cells (standard clinical doses of venetoclax or teriflunomide produce peak plasma concentrations of up to 2μM and 100μM, respectively). Nucleotide levels measured by LC-MS/MS at 24 hours. Quantifications by reference to assembled standard curves. Independent experiments, triplicate (data for K562 are duplicate because of LC injection error). Means ± SD. P values from paired 1-sided t test, teriflunomide vs vehicle. P values for venetoclax vs vehicle were all >.05. Aggregated data and analyses, including for adenine triphosphate and guanine triphosphate, are shown in supplemental Figure 1. Mut, mutated; Teri, teriflunomide; Ven, venetoclax; UTP, uridine triphosphate.

Venetoclax and teriflunomide effects on CTP and dCTP levels. (A) BAX is a p53 target gene that is approximately twofold less expressed in TP53-mutated vs WT TP53 AML cells, whereas BCL2 and BAK1 are similarly expressed. TCGA RNA-sequencing gene-level log2(x+1) transformed RSEM normalized counts, primary AML cells containing WT TP53 (no TP53 mutations or deletions by GISTIC threshold analyses of copy number; n = 129) or containing mutated TP53 and complex (≥3) cytogenetic abnormalities (n = 16). P value from unpaired 2-sided t test. (B) Teriflunomide produced larger decreases in CTP and dCTP in TP53-mutated and WT-TP53 AML cells than venetoclax. Venetoclax 2μM (20nM for MOLM13) or teriflunomide 20μM were added once to THP1, K562, and MOLM13 AML cells (standard clinical doses of venetoclax or teriflunomide produce peak plasma concentrations of up to 2μM and 100μM, respectively). Nucleotide levels measured by LC-MS/MS at 24 hours. Quantifications by reference to assembled standard curves. Independent experiments, triplicate (data for K562 are duplicate because of LC injection error). Means ± SD. P values from paired 1-sided t test, teriflunomide vs vehicle. P values for venetoclax vs vehicle were all >.05. Aggregated data and analyses, including for adenine triphosphate and guanine triphosphate, are shown in supplemental Figure 1. Mut, mutated; Teri, teriflunomide; Ven, venetoclax; UTP, uridine triphosphate.

Thus, clinically relevant concentrations of teriflunomide had selective and greater effects on CTP or dCTP levels than venetoclax.

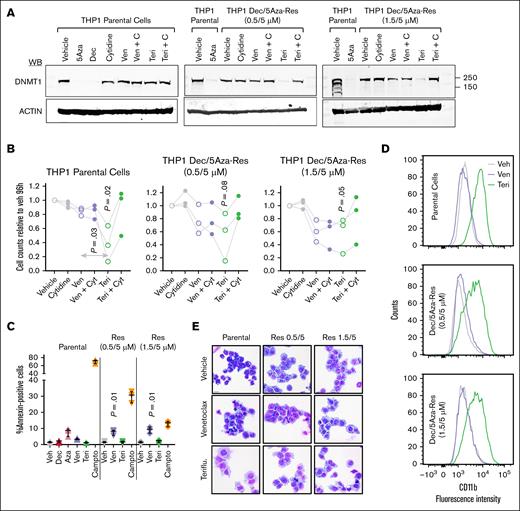

Teriflunomide but not venetoclax renewed DNMT1 depletion by HMA in HMA-resistant AML cells

We therefore compared the ability of venetoclax vs teriflunomide to renew DNMT1 depletion and cytoreduce HMA-resistant THP1. Teriflunomide renewed DNMT1 depletion (the cells were cultured continuously in HMA) to a larger extent than venetoclax (Figure 3A). Consistent with the mechanism for renewed DNMT1 depletion being inhibition of pyrimidine synthesis, it was prevented by adding 100μM cytidine to the media (Figure 3A). Cell-fate consequences were then examined. Teriflunomide more potently cytoreduced parental THP1 than venetoclax, whereas HMA-resistant THP1 were cytoreduced to a comparable extent by both teriflunomide and venetoclax, especially in HMA-resistant THP1 cultured in the higher concentration of HMA (1.5/5 vs 0.5/5μM; Figure 3B). Cytidine supplementation rescued parental and HMA-resistant THP1 from teriflunomide but did not rescue from venetoclax (Figure 3B). Teriflunomide did not activate apoptosis in parental or HMA-resistant THP1, measured by flow cytometry for Annexin V staining and by fluorometric assays for caspase 3 and 7 activation (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 2A-B). Although venetoclax did not activate apoptosis in parental THP1, it did significantly activate apoptosis in the HMA-resistant cells (Figure 3C; supplemental Figure 2A-B). Rather, teriflunomide renewed lineage maturation, shown by upregulation of granulomonocytic differentiation marker CD11b measured by flow cytometry, and by cell morphology seen in Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations in both parental and HMA-resistant THP1 (Figure 3D-E). Venetoclax did not renew lineage maturation of parental or HMA-resistant THP1 (Figure 3D-E).

Teriflunomide renewed DNMT1 depletion in HMA-resistant AML cells to a greater extent than venetoclax. (A) Teriflunomide renewed DNMT1 depletion in HMA-resistant THP1. Parental and HMA-resistant TP53-mutated AML cells (THP1) (HMA-resistant THP1 cultured continuously in indicated concentrations of decitabine and 5-azacytidine), were treated with venetoclax 2μM, teriflunomide 20μM with and without cytidine 100μM for 24 hours. Western blots at 24 hours. (B) Cell counts. Cell counts at 96 hours by automated counter. Independent experiments in triplicate. P values, paired 2-sided t test, for teriflunomide vs vehicle. (C) Apoptosis activation measured by flow cytometry for Annexin V staining. Mean ± SD, raw data in supplemental Figure 2. P values from paired 2-sided t tests, compared with vehicle. Independent experiments in triplicate. (D) CD11b expression. Flow cytometry, counts normalized to mode. Vehicle, venetoclax 2 μM, or teriflunomide 20μM treatment for 120 hours. (E) Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations. Treatments as per panel D. Leica Upright Microscope-Orion. Original magnification ×400; scale bar, 20 μm. 5Aza, 5-azacytidine; Cyt, cytidine; Dec, decitabine; Res, resistant; Teri, teriflunomide; Veh, vehicle; Ven, venetoclax; WB, Western blot.

Teriflunomide renewed DNMT1 depletion in HMA-resistant AML cells to a greater extent than venetoclax. (A) Teriflunomide renewed DNMT1 depletion in HMA-resistant THP1. Parental and HMA-resistant TP53-mutated AML cells (THP1) (HMA-resistant THP1 cultured continuously in indicated concentrations of decitabine and 5-azacytidine), were treated with venetoclax 2μM, teriflunomide 20μM with and without cytidine 100μM for 24 hours. Western blots at 24 hours. (B) Cell counts. Cell counts at 96 hours by automated counter. Independent experiments in triplicate. P values, paired 2-sided t test, for teriflunomide vs vehicle. (C) Apoptosis activation measured by flow cytometry for Annexin V staining. Mean ± SD, raw data in supplemental Figure 2. P values from paired 2-sided t tests, compared with vehicle. Independent experiments in triplicate. (D) CD11b expression. Flow cytometry, counts normalized to mode. Vehicle, venetoclax 2 μM, or teriflunomide 20μM treatment for 120 hours. (E) Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations. Treatments as per panel D. Leica Upright Microscope-Orion. Original magnification ×400; scale bar, 20 μm. 5Aza, 5-azacytidine; Cyt, cytidine; Dec, decitabine; Res, resistant; Teri, teriflunomide; Veh, vehicle; Ven, venetoclax; WB, Western blot.

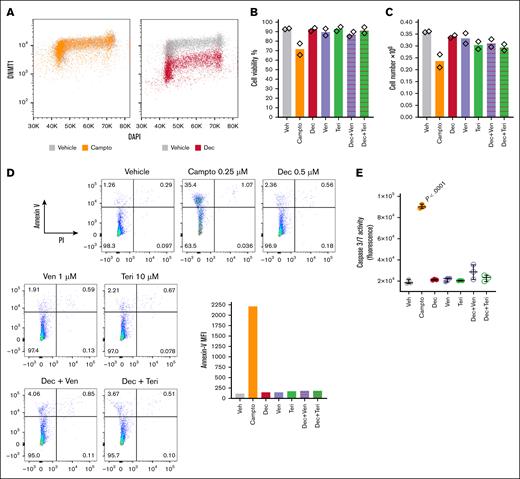

One problem with standard cytotoxic treatments for AML is activation of apoptosis (cytotoxicity) in normal hematopoiesis (unfavorable therapeutic index). Therefore, we also examined whether decitabine, teriflunomide, and venetoclax alone, and in combination, activated apoptosis in normal hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (NHSPC). Decitabine depleted DNMT1 protein from NHSPC, as expected, measured by flow cytometry (Figure 4A). These DNMT1-depleting concentrations of decitabine, alone or in combination with teriflunomide or venetoclax, neither decreased NHSPC viability nor produced major decreases in cell counts, measured by automated counter (Figure 4B-C), nor significantly activated apoptosis measured by flow cytometry for Annexin-V and propidium iodide staining (Figure 4D), and by caspase 3 and 7 activation by fluorescence assay (Figure 4E), with camptothecin treatment used as a positive control.

Decitabine at DNMT1-depleting concentrations, alone or in combination with teriflunomide or venetoclax, did not activate apoptosis in NHSPC compared with camptothecin positive control. CD34+ NHSPC isolated from umbilical cord blood were treated with vehicle, camptothecin 0.25μM, decitabine 0.5μM, venetoclax 1μM, teriflunomide 10μM, or combinations, as indicated. Measurements were performed after 24 hours of treatment. Independent biological replicates. (A) DNMT1 protein and DNA content (DAPI) was measured by flow cytometry in vehicle-, camptothecin-, and decitabine-treated cells. Fluorescence intensities. (B) Cell viability was measured by automated counter. (C) Cell count was measured by automated counter. (D) Apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry for Annexin V and PI staining. Bar graph shows Annexin V, MFI. (E) Apoptosis was also measured by fluorescence assay for caspase 3 and 7 activation. Technical triplicate from first biological replicate, similar results from second biological replicate. Significant increase observed only with camptothecin positive control, P values are from unpaired 2-sided t test. Campto, camptothecin; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Dec, decitabine; MFI, median fluorescence intensity; PI, propidium iodide; Teri, teriflunomide; Veh, vehicle; Ven, venetoclax.

Decitabine at DNMT1-depleting concentrations, alone or in combination with teriflunomide or venetoclax, did not activate apoptosis in NHSPC compared with camptothecin positive control. CD34+ NHSPC isolated from umbilical cord blood were treated with vehicle, camptothecin 0.25μM, decitabine 0.5μM, venetoclax 1μM, teriflunomide 10μM, or combinations, as indicated. Measurements were performed after 24 hours of treatment. Independent biological replicates. (A) DNMT1 protein and DNA content (DAPI) was measured by flow cytometry in vehicle-, camptothecin-, and decitabine-treated cells. Fluorescence intensities. (B) Cell viability was measured by automated counter. (C) Cell count was measured by automated counter. (D) Apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry for Annexin V and PI staining. Bar graph shows Annexin V, MFI. (E) Apoptosis was also measured by fluorescence assay for caspase 3 and 7 activation. Technical triplicate from first biological replicate, similar results from second biological replicate. Significant increase observed only with camptothecin positive control, P values are from unpaired 2-sided t test. Campto, camptothecin; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Dec, decitabine; MFI, median fluorescence intensity; PI, propidium iodide; Teri, teriflunomide; Veh, vehicle; Ven, venetoclax.

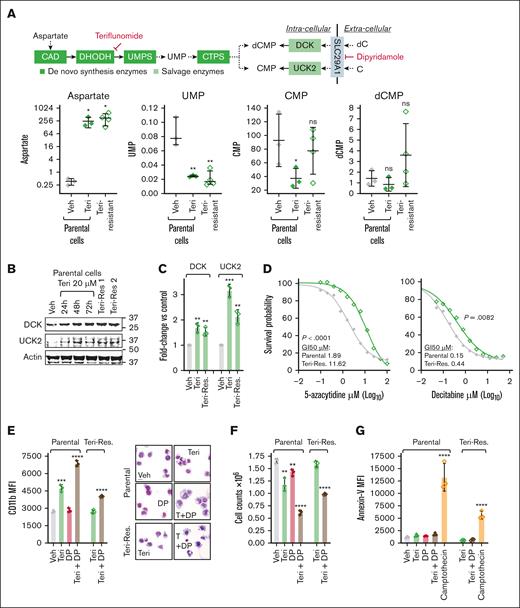

Inhibiting pyrimidine synthesis triggered compensatory increases in pyrimidine salvage

Thus, teriflunomide was active even as a single agent, cytoreducing parental and HMA-resistant TP53-mutated AML cells (THP1) via terminal lineage maturation. However, teriflunomide-resistant cells, exponentially expanding through 20μM teriflunomide, emerged within ∼40 days (supplemental Figure 3A). To investigate mechanisms for this resistance, we measured metabolites upstream and downstream in the pyrimidine de novo synthesis pathway (Figure 5A). Aspartate substrate, upstream in the pathway, increased acutely upon treating parental (teriflunomide naïve) THP1 with 20μM teriflunomide, and remained elevated also in teriflunomide-resistant THP1 continuously exposed to 20μM teriflunomide (Figure 5A). Uridine monophosphate, a metabolic product downstream of DHODH and UMPS in the pathway, decreased upon acute teriflunomide treatment and remained decreased also in teriflunomide-resistant AML cells (Figure 5A). However, cytidine monophosphate and deoxycytidine monophosphate, pyrimidine nucleotide products even further downstream, that can also be increased within cells via the pyrimidine salvage enzymes uridine cytidine kinase 2 (UCK2; that phosphorylates cytidine to cytidine monophosphate) and deoxycytidine kinase (DCK; that phosphorylates deoxycytidine to deoxycytidine monophosphate), partially recovered in teriflunomide-resistant THP1 (Figure 5A). DCK and UCK2 messenger RNA and protein were acutely upregulated by teriflunomide treatment of parental cells (Figure 5B-C; supplemental Figure 3B), and remained upregulated in teriflunomide-resistant cells (Figure 5B-C; supplemental Figure 3B).

Inhibiting pyrimidine synthesis triggered compensatory increases in pyrimidine salvage. (A) Teriflunomide treatment increased aspartate substrate that is upstream, and decreased UMP product that is downstream of DHODH and UMPS, in both teriflunomide-naïve (parental) and teriflunomide-resistant AML cells (THP1); products even further downstream that are also salvaged by DCK and UCK2, dCMP and CMP, were partially recovered. Parental THP1 were treated with teriflunomide 20μM for 72 hours. Teriflunomide-resistant THP1 had exponentially expanded through teriflunomide 20μM, emerging within ∼40 days. HR-LCMS analyses of extracts from equal numbers of cells, harvested from parental THP1 treated independently in triplicate, and in independent harvests in quadruplicate from teriflunomide-resistant THP1. Values are normalized to taurine levels in the same cells (taurine internal control). Mean ± SD. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01 (unpaired 2-sided t test). (B) DCK and UCK2, that rate limit salvage of deoxycytidine and cytidine into dCMP and CMP, respectively, were upregulated acutely by teriflunomide treatment, and remained upregulated in teriflunomide-resistant AML cells. Western blot. (C) Messenger RNA levels were also measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, using glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase internal control, and analyzed by Livak-Schmittgen method. Fold change vs vehicle-treated parental THP1 cells. Data represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001 (unpaired 2-sided t test). (D) Teriflunomide-resistant AML cells were also relatively resistant to the HMA. Teriflunomide-naïve (parental) and teriflunomide-resistant THP1 were treated with gradually increasing concentrations of 5-azacytidine (0-100μM) or decitabine (0-50μM) to identify concentrations that produced GI50. Cell counts by automated counter. P value from extra sum-of-squares F test. (E) Inhibiting pyrimidine salvage with dipyridamole (DP) enhanced differentiation induction by teriflunomide. Parental THP1 and teriflunomide-resistant THP1 were treated with the SLC29A1 inhibitor DP 10μM with or without teriflunomide 20μM. The granulomonocyte differentiation marker CD11b was measured by flow cytometry at 96 hours (left). Data represent MFI as mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 (unpaired 2-sided t test). Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations, imaged with a Leica Upright Microscope-Orion (right). Original magnification, ×400; scale bar, 20 μm. (F) AML cell numbers. Automated counter, methods/statistics per panel D. (G) Assay for apoptosis activation by flow cytometry for Annexin V staining at 24 hours. Camptothecin 0.25μM served as a positive control. Methods/statistics are described in panel D. CMP, cytidine monophosphate; CTPS, cytidine triphosphate synthetase; dCMP, deoxycytidine monophosphate; GI50, 50% growth inhibition; ns, nonsignificant; Res, resistant; Teri, teriflunomide; Veh, vehicle.

Inhibiting pyrimidine synthesis triggered compensatory increases in pyrimidine salvage. (A) Teriflunomide treatment increased aspartate substrate that is upstream, and decreased UMP product that is downstream of DHODH and UMPS, in both teriflunomide-naïve (parental) and teriflunomide-resistant AML cells (THP1); products even further downstream that are also salvaged by DCK and UCK2, dCMP and CMP, were partially recovered. Parental THP1 were treated with teriflunomide 20μM for 72 hours. Teriflunomide-resistant THP1 had exponentially expanded through teriflunomide 20μM, emerging within ∼40 days. HR-LCMS analyses of extracts from equal numbers of cells, harvested from parental THP1 treated independently in triplicate, and in independent harvests in quadruplicate from teriflunomide-resistant THP1. Values are normalized to taurine levels in the same cells (taurine internal control). Mean ± SD. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01 (unpaired 2-sided t test). (B) DCK and UCK2, that rate limit salvage of deoxycytidine and cytidine into dCMP and CMP, respectively, were upregulated acutely by teriflunomide treatment, and remained upregulated in teriflunomide-resistant AML cells. Western blot. (C) Messenger RNA levels were also measured by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, using glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase internal control, and analyzed by Livak-Schmittgen method. Fold change vs vehicle-treated parental THP1 cells. Data represent mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001 (unpaired 2-sided t test). (D) Teriflunomide-resistant AML cells were also relatively resistant to the HMA. Teriflunomide-naïve (parental) and teriflunomide-resistant THP1 were treated with gradually increasing concentrations of 5-azacytidine (0-100μM) or decitabine (0-50μM) to identify concentrations that produced GI50. Cell counts by automated counter. P value from extra sum-of-squares F test. (E) Inhibiting pyrimidine salvage with dipyridamole (DP) enhanced differentiation induction by teriflunomide. Parental THP1 and teriflunomide-resistant THP1 were treated with the SLC29A1 inhibitor DP 10μM with or without teriflunomide 20μM. The granulomonocyte differentiation marker CD11b was measured by flow cytometry at 96 hours (left). Data represent MFI as mean ± SD from 3 independent experiments. ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01; ∗∗∗P < .001; ∗∗∗∗P < .0001 (unpaired 2-sided t test). Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations, imaged with a Leica Upright Microscope-Orion (right). Original magnification, ×400; scale bar, 20 μm. (F) AML cell numbers. Automated counter, methods/statistics per panel D. (G) Assay for apoptosis activation by flow cytometry for Annexin V staining at 24 hours. Camptothecin 0.25μM served as a positive control. Methods/statistics are described in panel D. CMP, cytidine monophosphate; CTPS, cytidine triphosphate synthetase; dCMP, deoxycytidine monophosphate; GI50, 50% growth inhibition; ns, nonsignificant; Res, resistant; Teri, teriflunomide; Veh, vehicle.

A chronic increase in pyrimidine salvage that rescues AML cells from teriflunomide, might also rescue from HMA, which must compete with the larger internal pool of salvaged natural pyrimidines. Compared with teriflunomide-naïve THP1, teriflunomide-resistant THP1 were accordingly also relatively resistant to HMA, seen by the HMA concentrations needed to produce 50% growth inhibition (Figure 5D).

For further functional evaluation, we used dipyridamole to inhibit the cell membrane equilibrative nucleoside transporter SLC29A1 that transports pyrimidine and purine nucleosides. Dipyridamole (10μM) augmented the lineage-maturation effects of teriflunomide in both parental (teriflunomide naïve) and teriflunomide-resistant THP1, seen by flow cytometry for the granulomonocytic differentiation marker CD11b and for side scatter (Figure 5E; supplemental Figure 3C), cell morphology in Giemsa-stained cytospin preparations (Figure 5E), and cytoreduction (Figure 5F) without activation of apoptosis (flow cytometry for Annexin V staining; Figure 5G; supplemental Figure 3D).

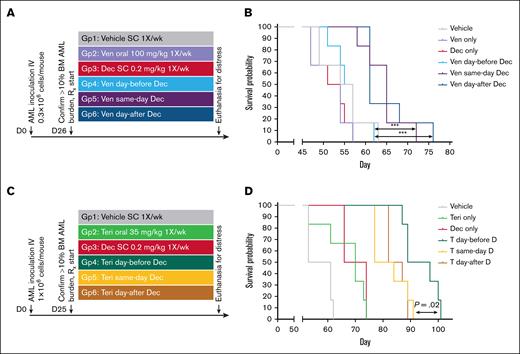

Timing of teriflunomide in relationship to HMA affects efficacy in vivo

Because inhibiting de novo synthesis upregulated DCK and UCK2, which rate limit uptake and processing of HMA, this suggested that timing of de novo synthesis inhibitors in relation to HMA might affect in vivo efficacy. We therefore compared scheduling venetoclax or teriflunomide the day before, the same day, or the day after a single dose of subcutaneous decitabine each week (decitabine dose and schedule selected for sustainable noncytotoxic targeting of DNMT1 in vivo, as previously described).5,7,8,10,37-45

To evaluate decitabine/venetoclax, NSG mice were tail-vein inoculated with 0.3 × 106 AML cells from a patient with AML that was resistant to cytarabine/daunorubicin and IV decitabine. After bone marrow engraftment to >10% human CD45+ (hCD45+) cells was confirmed in 3 mice, the remaining mice were randomized to treatment with (1) vehicle; (2) venetoclax 100 mg/kg oral gavage once per week; (3) decitabine 0.2 mg/kg subcutaneous once per week; (4) venetoclax the day before decitabine; (5) venetoclax on the same day as decitabine; and (6) venetoclax on the day after decitabine (Figure 6A). Mice were euthanized for signs of distress per the animal protocol, with blinding to treatment group. Time to distress (survival) was longest for same-day venetoclax/decitabine (median time to distress in days: vehicle, 54; venetoclax, 54; decitabine, 54; venetoclax day-before decitabine, 56; same day, 65; day after, 62; log-rank P < .001; Figure 6B). Bone marrow hCD45+ cell content at the time of euthanasia was measured using flow cytometry and demonstrated 20% to 30% in all groups (different timings for the different groups), suggesting eventual distress was from leukemia progression (supplemental Figure 4A). Similarly, spleen weights at time of euthanasia demonstrated splenomegaly in all groups (supplemental Figure 4B).

Schedules of venetoclax or teriflunomide in relationship to decitabine affect anti-AML efficacy in vivo. (A) Experiment schema evaluating different schedules of venetoclax in relationship to decitabine. NSG mice were tail-vein inoculated with 0.3 × 106 AML cells from a patient with cytarabine- and HMA-refractory AML. Treatments were initiated after confirmation of engraftment to >10% hCD45+ cells in the BM in 3 mice. (B) Time to distress. Mice were euthanized for signs of distress as per the animal protocol. P values from log-rank test. Leukemia burden in the marrow and spleen at time of euthanasia is shown in supplemental Figure 4A-B. (C) Experiment schema evaluating different schedules of teriflunomide in relationship to decitabine. NSG mice were tail-vein inoculated with 1 × 106 AML cells from a patient with TP53-mutated complex cytogenetics AML. Treatments were initiated after confirmation of engraftment to >10% hCD45+ cells in the BM in 3 mice. (D) Time to distress. Mice were euthanized for signs of distress as per the animal protocol. P values from log-rank tests. Leukemia burden in the marrow and spleen at time of euthanasia is shown in supplemental Figure 4B-C. BM, bone marrow; D, decitabine; Dec, decitabine; SC, subcutaneous; Teri, teriflunomide; T, teriflunomide; Ven, venetoclax.

Schedules of venetoclax or teriflunomide in relationship to decitabine affect anti-AML efficacy in vivo. (A) Experiment schema evaluating different schedules of venetoclax in relationship to decitabine. NSG mice were tail-vein inoculated with 0.3 × 106 AML cells from a patient with cytarabine- and HMA-refractory AML. Treatments were initiated after confirmation of engraftment to >10% hCD45+ cells in the BM in 3 mice. (B) Time to distress. Mice were euthanized for signs of distress as per the animal protocol. P values from log-rank test. Leukemia burden in the marrow and spleen at time of euthanasia is shown in supplemental Figure 4A-B. (C) Experiment schema evaluating different schedules of teriflunomide in relationship to decitabine. NSG mice were tail-vein inoculated with 1 × 106 AML cells from a patient with TP53-mutated complex cytogenetics AML. Treatments were initiated after confirmation of engraftment to >10% hCD45+ cells in the BM in 3 mice. (D) Time to distress. Mice were euthanized for signs of distress as per the animal protocol. P values from log-rank tests. Leukemia burden in the marrow and spleen at time of euthanasia is shown in supplemental Figure 4B-C. BM, bone marrow; D, decitabine; Dec, decitabine; SC, subcutaneous; Teri, teriflunomide; T, teriflunomide; Ven, venetoclax.

To evaluate decitabine/teriflunomide, NSG mice were tail-vein inoculated with 1 × 106 AML cells from a patient with TP53-mutated complex cytogenetics AML. After bone marrow engraftment to >10% hCD45+ cells was confirmed in 3 mice, the remaining mice were randomized to treatment with (n = 6 per group) (1) vehicle; (2) teriflunomide 35 mg/kg oral gavage once per week; (3) decitabine 0.2 mg/kg subcutaneous once per week; (4) teriflunomide on the day before decitabine; (5) teriflunomide on the same day as decitabine; and (6) teriflunomide on the day after decitabine (Figure 6C). Mice were euthanized for signs of distress per the animal protocol, with blinding to treatment group. By contrast to the results with venetoclax/decitabine, time to distress was longest for teriflunomide day-before decitabine (median time to distress in days: vehicle, 50; teriflunomide, 70; decitabine, 70; day before, 95; same day and day after, 85; log-rank P = .02; Figure 6D). Bone marrow hCD45+ cell content at the time of euthanasia was measured using flow cytometry and demonstrated >50% in all groups (different timings for the different groups), suggesting eventual distress was from leukemia progression (supplemental Figure 4C). Similarly, spleen weights at time of euthanasia demonstrated splenomegaly in all groups (supplemental Figure 4D).

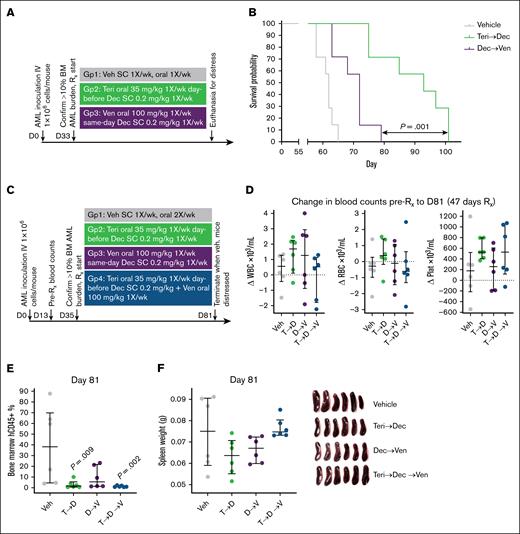

We then compared the optimal schedule of teriflunomide/decitabine with the optimal schedule of venetoclax/decitabine in NSG mice tail-vein inoculated with 1 × 106 AML cells from a patient with TP53-mutated complex cytogenetics AML. Again, treatment was started after confirmation of bone marrow engraftment to >10% hCD45+ cells in 3 mice; teriflunomide/decitabine 35/0.2 mg/kg once per week was superior to venetoclax/decitabine 100/0.2 mg/kg once per week (n = 7 per group; log-rank P = .001; median time to distress in days: vehicle, 65; venetoclax/decitabine, 72; and teriflunomide/decitabine, 95; Figure 7A-B; supplemental Figure 4E-F). The experiment was then repeated, incorporating an additional treatment group of triplet teriflunomide/decitabine/venetoclax. All mice were euthanized at the same time point (day 81) when vehicle-treated mice demonstrated signs of distress, to allow meaningful intergroup comparisons of leukemia burden (Figure 7C). Peripheral blood red blood cell and platelet counts were highest, and bone marrow leukemia burden (flow cytometry for hCD45+ cells) was lowest, in the mice receiving teriflunomide/decitabine vs the other groups (Figure 7D-E). Mice receiving the triplet combination had significantly less bone marrow leukemia burden vs vehicle-treated mice, however, their spleen leukemia burden was not decreased (cytidine deaminase that catabolizes HMA is highly expressed in reticulo-endothelial tissues and can cause intertissue differences in HMA response22,37; Figure 7F-G).

The optimal schedule of teriflunomide/HMA was more efficacious than the optimal schedule of venetoclax/HMA to treat TP53-mutated complex cytogenetics AML. NSG mice were tail-vein inoculated with 1 × 106 AML cells from a patient with TP53-mutated complex cytogenetics AML. Treatment was started after confirmation of BM engraftment to >10% hCD45+ cells in 3 mice. (A) Experiment schema. (B) Time to distress. Mice were euthanized for signs of distress as per the animal protocol. P values are from log-rank tests. Leukemia burden in the marrow and spleen at time of euthanasia is shown in supplemental Figure 4E-F. (C) Experiment schema for repeat experiment in which all mice were euthanized at a fixed time point (when vehicle-treated mice demonstrated signs of distress at day 81, after 47 days of treatment for all groups). (D) Change in WBC, RBC, and platelet counts between days 13 and 81 (47 days of treatment). (E) BM leukemia burden (percentage of hCD45+ cells) at day 81. Only significant P values (P < .05) are shown, 2-sided Mann-Whitney U test, vs vehicle. (F) Spleen leukemia burden measured by spleen weights at day 81. D, decitabine; Dec, decitabine; Plat, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; Rx, treatment; SC, subcutaneous; T, teriflunomide; Teri, teriflunomide; Veh, vehicle; Ven, venetoclax; WBC, white blood cell.

The optimal schedule of teriflunomide/HMA was more efficacious than the optimal schedule of venetoclax/HMA to treat TP53-mutated complex cytogenetics AML. NSG mice were tail-vein inoculated with 1 × 106 AML cells from a patient with TP53-mutated complex cytogenetics AML. Treatment was started after confirmation of BM engraftment to >10% hCD45+ cells in 3 mice. (A) Experiment schema. (B) Time to distress. Mice were euthanized for signs of distress as per the animal protocol. P values are from log-rank tests. Leukemia burden in the marrow and spleen at time of euthanasia is shown in supplemental Figure 4E-F. (C) Experiment schema for repeat experiment in which all mice were euthanized at a fixed time point (when vehicle-treated mice demonstrated signs of distress at day 81, after 47 days of treatment for all groups). (D) Change in WBC, RBC, and platelet counts between days 13 and 81 (47 days of treatment). (E) BM leukemia burden (percentage of hCD45+ cells) at day 81. Only significant P values (P < .05) are shown, 2-sided Mann-Whitney U test, vs vehicle. (F) Spleen leukemia burden measured by spleen weights at day 81. D, decitabine; Dec, decitabine; Plat, platelet; RBC, red blood cell; Rx, treatment; SC, subcutaneous; T, teriflunomide; Teri, teriflunomide; Veh, vehicle; Ven, venetoclax; WBC, white blood cell.

Discussion

HMAs are processed into a pyrimidine nucleotide analog, aza-dCTP, which, to deplete DNMT1, must compete with endogenous dCTP. Here, we found that upregulation of the initial and rate-limiting enzyme in de novo pyrimidine synthesis, CAD, and accompanying elevated dCTP and/or CTP, contributes to the failure of HMAs to deplete DNMT1 and hence overt treatment resistance.8,22 Motivating these analyses, we had previously observed elevated CAD in patient bone marrow aspirates at time of relapse on HMA therapy.22 Moreover, TP53 mutations may prime for this mode of resistance, because CAD expression was constitutively higher in Tp53-knockout vs wild-type Tp53 murine GMP, and in TP53-mutated vs wild-type TP53 primary AML cells, likely as a compensatory response to less expression of another key de novo pyrimidine and purine synthesis enzyme, RRM2B, which is a p53 target gene.25-27 Inhibiting de novo pyrimidine synthesis with the DHODH inhibitor teriflunomide resumed DNMT1 depletion and terminated replications of HMA-resistant AML cells without activating apoptosis. Although teriflunomide, a clinical drug approved to treat autoimmune disease, has been shown previously to augment 5-azacytidine activity against AML cells in vitro,46,47 neither teriflunomide nor its prodrug leflunomide had been evaluated in preclinical in vivo or clinical studies to treat myeloid neoplasms, alone or in combination with 5-azacytidine or decitabine. Here, in a PDX model of TP53-mutated, complex cytogenetics chemotherapy-refractory AML, teriflunomide/decitabine was substantially more beneficial than venetoclax/decitabine or decitabine.

Inhibiting pyrimidine synthesis with teriflunomide triggered compensatory upregulations in pyrimidine salvage, including increases in DCK and UCK2 that rate limit uptake and processing of the HMA. Along these lines, cytidine supplementation rescued AML cells from teriflunomide,48 and resistance to teriflunomide as a single agent was rapid (adaptive resistance, reviewed in Saunthararajah49). The automatic upregulations of pyrimidine salvage could be anticipated and leveraged to improve therapy; scheduling teriflunomide on the day before the HMA produced a greater anti-AML effect in vivo than same-day or day-after scheduling. In contrast, continuous exposure to teriflunomide was counterproductive, because chronic compensatory pyrimidine salvage not only rescued AML cells from teriflunomide (teriflunomide resistance) but also decreased sensitivity to HMA, which must compete against salvaged natural pyrimidines (HMA resistance). We thus used timed, intermittent (metronomic) schedules of drug administration to allow adaptive metabolic shifts to revert closer to baseline between treatment exposures, building on our previous preclinical in vivo and clinical work with decitabine (decitabine also triggers adaptive reactions from the pyrimidine metabolism network).5,7,8,10,24,37-41,50-52

The BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax can also inhibit de novo pyrimidine synthesis34 and is approved to treat AML when combined with HMA. However, venetoclax has a BAX-dependent mechanism of action, and BAX, a p53 target gene (reviewed in Wei et al36), was decreased in TP53-mutated AML cells. Supporting relevance of this observation, BAX loss-of-function mutations (1) caused AML cell resistance to venetoclax in unbiased genetic screens35; (2) were found in 17% of patients with AML relapsing after venetoclax-containing therapy, but in 6% of relapses, and at low variant allele frequencies, after venetoclax-free cytotoxic therapy53; and (3) were found in myeloid cells from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia treated chronically with venetoclax.54 Cytidine supplementation, that rescued AML cells from teriflunomide,48 did not rescue HMA-resistant AML cells from venetoclax in vitro. Consequences of mitochondrial membrane depolarization other than inhibition of pyrimidine synthesis may therefore underpin venetoclax cooperation with HMA; HMA perturbations of pyrimidine metabolism8,22 trigger an integrated stress response from AML cells.55-57 One facet of this stress response is priming for apoptosis via upregulation of the proapoptotic BCL2-family protein PMAIP1 (NOXA). PMAIP1 degrades antiapoptotic BCL2-family proteins MCL1 and BCL2L1 (BCL-xL), creating greater dependence on antiapoptosis BCL2 in a limited time window after the HMA.55-57 Venetoclax was thus able to activate apoptosis in a portion of HMA-resistant AML cells (cells continuously exposed to HMA), more so than in HMA-naïve counterparts. Also consistent with these mechanisms, the cytoreductive effects of venetoclax were greater in the HMA-resistant THP1 cultured in higher concentrations of HMA. Also, in line with these mechanisms, optimal timing of venetoclax in vivo was on the same day (venetoclax plasma half-life is >24 hours) or the day after the HMA, contrasting with optimal timing for teriflunomide, which was on the day before the HMA.

Preclinical and clinical studies of other pyrimidine synthesis inhibitors with a HMA have been conducted. First, hydroxyurea inhibits ribonucleotide reductase that converts both pyrimidine and purine RNA into DNA, including 5-azacytidine toward DNMT1-depleting aza-dCTP. Hydroxyurea accordingly antagonized DNMT1 depletion by 5-azacytidine in vitro,58,59 and there were no responses in a clinical trial of combination of hydroxyurea with 5-azacytidine.59 We evaluated hydroxyurea/decitabine in a preclinical PDX model of chemotherapy-refractory AML, and did not observe benefit,22 possibly because of direct cytotoxicity of hydroxyurea to NHSPC, greater inhibition of purine than pyrimidine deoxynucleotide synthesis, and hydroxyurea-induced cytostatis that antagonizes S-phase dependent DNMT1 targeting. Second, pyrazofurin, that inhibits UMPS, augmented 5-azacytidine activity in vitro.60 However, in a clinical trial that increased pyrazofurin dose against a fixed, relatively high dose of 5-azacytidine, there were no gains in tumor response but major increases in mucosal and marrow toxicity.61 Third, N-(phosphonacetyl)-L-aspartate inhibits CAD, and also augmented 5-azacytidine activity in vitro.62 However, clinical development of parenteral N-(phosphonacetyl)-L-aspartate was curtailed as high doses were needed to produce systemic CAD inhibition, and these doses were toxic.63 Fourth, PTC299 is a DHODH inhibitor, which generated synergistic cytotoxic effects against malignant myeloid cells when combined with decitabine or 5-azacytidine in vitro and in vivo64 (DHODH inhibitors other than teriflunomide, eg, brequinar, can be cytotoxic).65,66 Clinical trials of PTC299 alone to treat myeloid malignancies (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03761069) have been terminated with no results reported at time of writing. Fifth, 2 other DHODH inhibitors, RP7214 and JNJ-74856665, were combined with 5-azacytidine in clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT05246384 and NCT04609826, respectively); these trials have also been terminated with no results reported at time of writing. Previous data thus seem to caution importance of preserving a favorable therapeutic index (avoiding cytotoxicity to NHSPC) in proposing solutions for HMA resistance. Also, the present data suggest that adaptive responses of the pyrimidine metabolism network should be anticipated, for example, by (1) metronomic schedules of de novo synthesis inhibitor administration (not daily), to allow automatic salvage increases to revert toward baseline between drug exposures; and (2) sequencing before the HMA, to leverage automatic increases in salvage to augment HMA uptake.

Major limitations of these studies are that we did not compare metronomic teriflunomide/decitabine vs venetoclax/decitabine against wild-type TP53 AML in vivo. Similarly, our examination of triplet teriflunomide/decitabine/venetoclax was too limited to render conclusions in comparison with doublet teriflunomide/decitabine, especially to treat wild-type TP53 AML. Superiority of metronomic teriflunomide/decitabine vs venetoclax/HMA or HMA alone to treat TP53-mutated AML can only be definitively determined in prospective clinical trials. Such clinical evaluation is feasible because we used clinical agents applied for specific and measurable molecular pharmacodynamic effects, at human-equivalent exposures known to be safe. Specifically, decitabine at minimum biologically effective dose to deplete DNMT1 and scheduled metronomically, has been used for multiyear therapy of myeloid malignancies, with a safety margin that has allowed sustained combinations with other targeted agents including metronomic venetoclax.7,38,40,41,51,52,67 Epigenetic modification by decitabine at a minimum biologically effective dose shifts myeloid outputs toward platelet/red cells and away from granulocyte/monocytes.42,68 Thus, a blood count profile observed early in therapy, that is distinct from that observed with cytotoxic therapy, is concurrent white count decreases and platelet/red cell increases.5-7,38,39,42,43,68,69 Similarly, DHODH targeting with leflunomide or teriflunomide, at doses that produce serum concentrations up to 100μM, is routine multiyear therapy to treat rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis in adults and children, with a noncytotoxic clinical profile of activity; in vitro, neither teriflunomide alone70 nor teriflunomide/decitabine activated apoptosis in NHSPC.

In sum, mechanisms of resistance, therapeutic index, and in vivo proof of principle data suggest that a candidate solution for early relapse of TP53-mutated myeloid neoplasms treated with an HMA or HMA/venetoclax is combination with teriflunomide (or prodrug leflunomide), at doses selected for noncytotoxic molecular-targeted effects against DNMT1 and DHODH, and by timed, intermittent schedules that anticipate and leverage adaptive responses of the pyrimidine metabolism network.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge administrative support from JoAnn Bandera and facility support from the Biological Resources Unit, FlowCore, and Imaging Core of the Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute.

Authorship

Contribution: S.B., Z.A.M.Z., X.G., L.C., R.M., N.M., and Y.S. performed experiments and research; S.B., Z.A.M.Z., X.G., L.C., R.M., N.M., M.S., A.J., K.F., B.T., M.G., A.V., and Y.S. analyzed data; Y.S. generated hypotheses, designed research, obtained funding, and wrote the manuscript; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: Y.S. reports stock ownership in EpiDestiny and Treebough; and patents related to tetrahydrouridine, decitabine, and 5-azacytidine (US 9,259,469 B2; US 9,265,785 B2; and US 9,895,391 B2), and cancer differentiation therapy (US 9,926,316 B2). The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Yogen Saunthararajah, Department of Translational Hematology and Oncology Research, Taussig Cancer Institute, Cleveland Clinic, 9500 Euclid Ave, NE6-313, Cleveland, OH 44195; email: saunthy@ccf.org.

References

Author notes

S.B., Z.A.M.Z., and X.G. contributed equally to this study.

Original data are available on request from the corresponding author, Yogen Sauntharajah (saunthy@ccf.org).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.